Earth Returns Our Love

Let’s be honest: Writing the land is impossible. The land writes itself, sings the song of itself in languages older than words, in creak and croak and thunderclap, in wail of loonsong, murmur of leaf rustle, insect hum, wolf howl. The languages of people, various and rich but so new in the pageant of life, are wholly inadequate to capture the land’s music.

But . . . attempting to write the land is noble. And delightful. Perhaps even essential. To add our compositions, imperfect and incomplete as they may be, to the land’s great symphony, joining our human song to the chorus of voices helps us make sense of our place and purpose in the diversity of life.

Our moment in time, with its entwined crisis of climate chaos and ecological unraveling, offers up a continuous mix of horrors, current and anticipated, to contemplate. The land, however, despite its sufferings, offers daily an antidote to despair. What better way to avoid forethought of grief than to greet one’s wild cousins, hemlock and moose, and acknowledge the wind, moon, and sun? To be cheered by flower, waved at by leaf, sung to by warbler—these daily blessings ground us.

In a spirit of reciprocity, many of us work to safeguard the ground that grounds us. This work, in our culture, has come to be known as “conservation,” a term encompassing a wide array of actions with legal and ethical foundations, and which can permanently protect specific places. The parks and wilderness areas we treasure, the undammed rivers, the natural habitats supporting wildlife, the scenic vistas of unmarred country . . . where such beauty and wildness remain it is generally not because the forces of development haven’t yet arrived but because people who loved the land used their own wild and precious lives resisting those forces. And were successful.

In America’s fractious body politic, the land trust movement is remarkably nonpolitical, bipartisan, even hopeful. It’s a vanishingly rare area of civic life that attracts people from across the political spectrum, whose interests range from conserving local farms and timberlands to setting aside great swaths of the planet from human domination and letting nature rewild—that is to say, heal, places degraded by human exploitation. The commonality within this broad movement is devotion to the land.

If expanding the number of people who feel this devotion and express it through conservation efforts is crucial to a beautiful future for humanity and all our relations on Earth (and I do believe it is), how might that come to pass? How will we win hearts and minds to the righteous cause of wildness? Surely the land’s intrinsic beauty and wild life—and human interpreters of these attributes—will play central roles in rewilding ourselves, a fundamental task if we are to regain responsible citizenship in the biotic community.

In this urgent work of interpretation, celebration, and reconnection we have much to learn from land lovers of various kinds—amateur naturalists, formally trained ecologists, community elders, organic farmers, low-impact loggers, wilderness champions . . . and poets.

Yes, poets, the concise storytellers, armed with visions. The voices of courage that sometimes, when the stars and words align, perform the shaman’s task, guiding us to look beyond surfaces and tap our individual sense of wonder. Thanks always to these guides who see our fellow members in the land community and recognize them as family. Who in the favor of their poetry remind us that Earth returns our love.

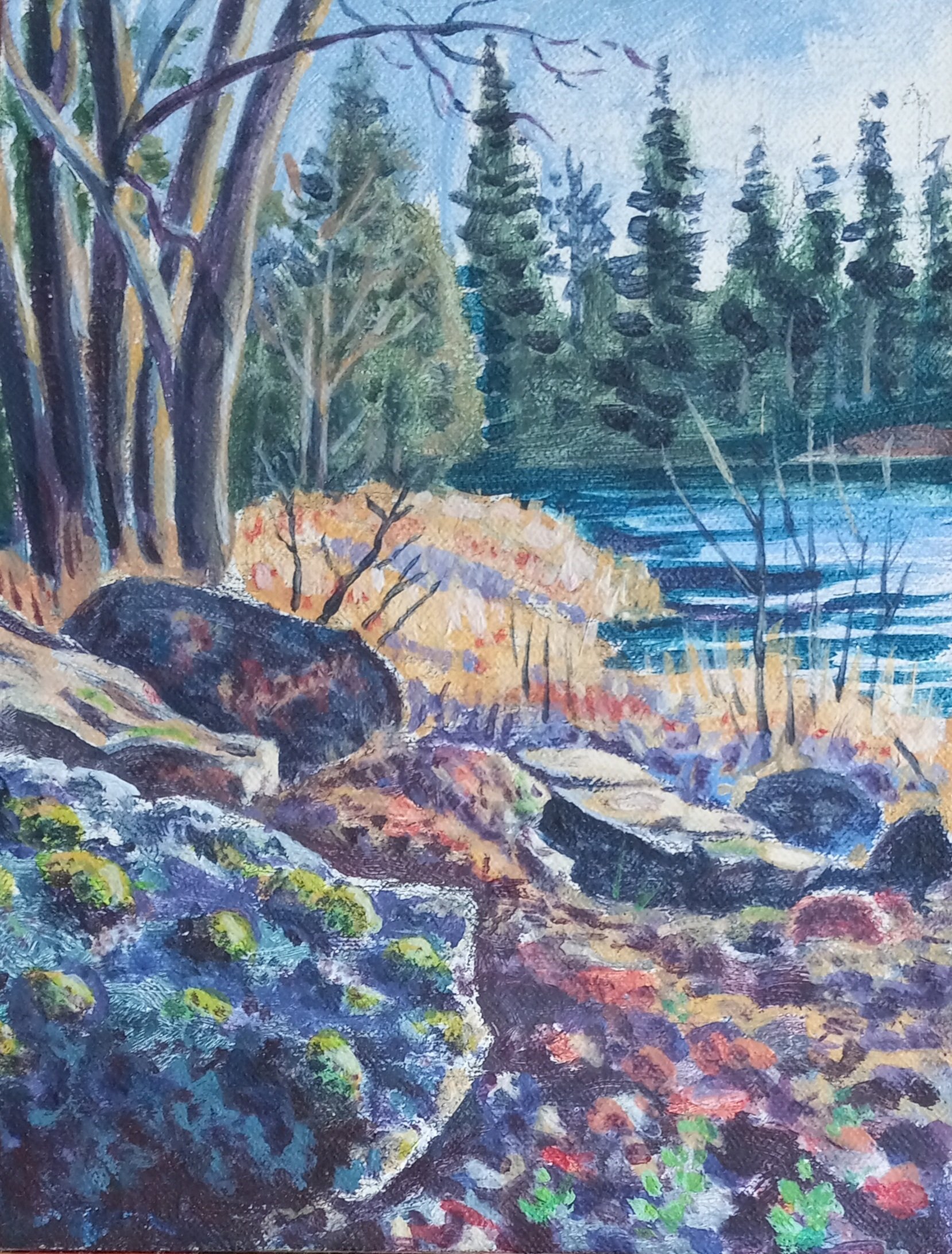

Banks of the Mattawamkeag, Acrylic on hard board © by Susan D. Szwed

Tom Butler is the author or volume editor of more than a dozen books including Wildlands Philanthropy, Protecting the Wild, and On Beauty: Douglas R. Tompkins—Aesthetics and Activism. He was a founding board member and past president of Northeast Wilderness Trust, where he now serves as senior fellow, and currently serves on the board of Tompkins Conservation. He edited Wild Earth for many years.

This essay first appeared as the Foreword to: Writing the Land: Northeast; editor Lis McLoughlin; 2021; Human Error Publishing Wendell, Massachusetts. Please visit WTL’s websites: www.writingtheland.org and www.nature-culture.net.

Click here for some poems from Writing the Land - and to learn more about the project.