By the Numbers—Conservation’s Value for Communities

An Interview with Jonathan Thompson

Editor’s Note: Nearly twenty years ago, when the Harvard Forest was seeking to regionalize its Long Term Ecological Research program by integrating an understanding of the natural and human forces shaping and poised to determine the future of the New England landscape, a colleague from Oregon alerted me to the fact that his student, an accomplished ecologist and ecological modeler who had just finished his PhD, was keen to return home to New England. By hiring Jonathan Thompson, we helped set up a sound future for science and leadership at the Harvard Forest, initiating a series of studies that help to explore critical ecological patterns and processes across our six-state region and beyond. Forging collaborations with social and physical scientists, ecologists, and foresters, and applying a unique suite of data from archives and remote sensing to human surveys, Jonathan’s research yields a basic understanding of fundamental processes that has direct application to real-world problems of land conservation and planning. – David Foster

Marissa Latshaw (ML): For the past 10 years, your lab has been studying land protection as one of the important processes shaping the future of New England, shining a light on what’s working and what isn’t. How did you approach this work?

Jonathan Thompson (JT): Protecting land, whether by establishing parks, conservation easements, or wilderness areas, is the most widely used tool in the conservationist’s toolbox. It is often referred to as a coarse filter approach to conservation. By dedicating specific areas for natural uses while restricting other land uses, we hope to sustain and possibly enhance the region’s overall biodiversity and ecosystem function. Of course, land is expensive, and when we protect it for nature, then it cannot be used for other economic activities. Not surprisingly, therefore, land protection can be controversial. Communities worry that land protection is bad for business—that it costs jobs and tax revenue, and that it impedes economic growth. My research quantifies the impacts of land protection for both people and nature.

Conservation is a slow process, and the immediate impacts of land protection are not obvious. The day after the paperwork to protect a new parcel is signed, the land looks pretty much the same as it did the day before, and it often looks similar to all the adjacent unprotected land. Similarly, the long-term impacts are not well understood. Outside of a few iconic parks like Yellowstone, the ecological and economic impacts of protecting land have not been quantified. I am interested in understanding the impacts of protecting land and determining what types of protections work best for achieving specific outcomes under different conditions.

My partner in much of this research is Kate Sims, a Professor of Environmental Economics at Amherst College. Together, we’ve been working to quantify the ecological and economic impacts of land protection in New England. It’s an excellent place to do this research because so many protected areas have been established over the past 50 years by so many different organizations, using a variety of protection mechanisms. All this variation allows for a robust study design.

“Communities worry that land protection is bad for business—that it costs jobs and tax revenue, and that it impedes economic growth.”

ML: Unemployment is one of the most commonly cited indicators of economic health. How does protecting land impact employment levels?

JT: First, we asked how land protection in New England affects key economic indicators, including unemployment. We showed that, for the approximately 1,500 towns and cities in the region from 1990 through 2015, new land protection tended to help local economies. Over those 25 years, protection moderately increased local employment numbers and the labor force, without reducing new housing permits. To put these findings in perspective, suppose a town with 30,000 people employed increases the amount of land protected from 10 percent to 15 percent. That is a 50 percent increase, which our results suggest would translate into a 1.5 percent increase in the number of people employed, or about 350 additional people employed.

We used a statistical approach that allows us to isolate the economic outcomes that were caused by land protection. We controlled for potentially confounding factors, including metro-region growth trends, fluctuations in employment by time period, and land protection actions by neighboring towns. We also controlled for constant features of each town, including wealth levels and proximity to the coast and to population centers. We found that higher levels of land protection led to greater numbers of people employed, especially in rural areas.

Interestingly, we see that economic impacts of land protection vary depending on attributes of the local community. We sometimes refer to this as the “Lincoln, Lincoln, Lincoln” phenomenon. In the affluent leafy suburb of Lincoln, Massachusetts, land protection confers amenity values where the nice open spaces raise nearby property values. In contrast, in Lincoln, New Hampshire, in the White Mountains, the economic impacts of land protection are associated with recreation opportunities and the associated jobs in hotels and with fishing outfitters. And then in Lincoln, Maine, where there are large protected timberlands, the benefits relate to maintenance of rural timber economies.

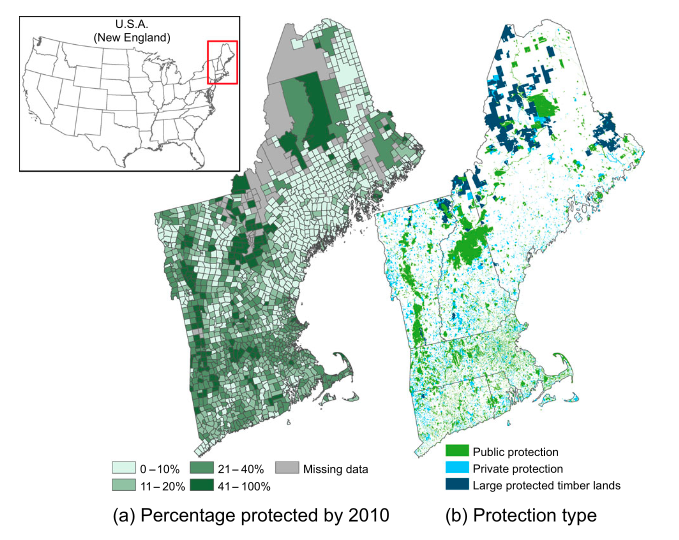

This figure illustrates protected land using 1,501 units of land in the study area of New England. As conservation expands into more densely populated areas, rigorous evaluations of both public and private land protection are critical to understanding their economic and social impacts. Figure from “Assessing the Local Economic Impacts of Land Protection” by Katharine R. E. Sims, Jonathan R. Thompson, Spencer R. Meyer, Christoph Nolte, and Joshua S. Plisinski

“We found that higher levels of land protection led to greater numbers of people employed, especially in rural areas.”

ML: Some have expressed the concern that increasing protected land can reduce the overall tax base and drive up individual property taxes. What are the factors or circumstances that might cause this to happen? What can be done to prevent this outcome?

JT: Our study of how land protection impacts property taxes is a great example where we set out to test the validity of a community concern about land protection that was really producing a lot of friction in town halls throughout the region. The long-held conventional wisdom suggests that because land protected (either through conservation restrictions or under fee ownership by public and nonprofit organizations) is frequently tax-exempt or taxed at lower rates, it will erode local property tax bases and result in higher property tax rates for other landowners. This is a reasonable concern. However, there are reasons that this concern might not be warranted. For example, because protected lands require fewer government services—such as for police, roads, and schools—and because protection often lifts property values through the amenity effects I mentioned before, it might be that protecting land actually reduces property taxes. We decided to find out.

We built and continue to maintain a database that combines information on property tax rates, property tax levies, taxable property value, and new protected lands for more than 1,400 municipalities in the region, spanning from 1990 to 2020. Analyzing these data, we see only small effects of land protection on property taxes. To put this in context, we found that, on average, 100 acres of new protection in a town is associated with an increase in a homeowner’s annual property tax bill of just $1.16 per $100,000 of property value. But there are slightly greater impacts for towns that are growing slowly, have lower median household incomes, or fewer second homes.

This figure illustrates the spatial variation in property tax rates (A) and tax bases (B) within the study region, which included more than 1,400 municipalities across five New England states. Figure from “Does Land Conservation Raise Property Taxes? Evidence From New England Cities and Towns” by Alexey V. Kalinin, Katharine R.E. Sims, Spencer R. Meyer, and Jonathan R. Thompson

ML: We’ve been talking about communities in general terms, but certainly the benefits of land protection do not reach all communities equally. What has your research shown about land access for historically underserved communities?

JT: About a quarter of all the land in New England has some type of protected status. Given how much land is protected, you might think that everyone in the region would have access to protected open space and the benefits it provides. However, we know that many public goods are not equitably distributed. We used our protected lands database to ask whether there are disparities in access to protected open space related to factors of social marginalization, like race and income.

We found that households in census tracts in the lowest income quartile tend to have access to just half as much protected land as those in the highest quartile. Similarly, communities with the highest proportion of people of color have about 60 percent as much nearby protected land. These differences are not just reflecting the differences between the city and the country. In fact, these patterns persist across rural, exurban, and urban areas, and are present in historical as well as recent patterns of land protection.

After documenting these patterns, we developed a web-based mapping tool that conservation groups and governments can use to assess the demographics around potential conservation sites. I’ve been super impressed with how many different organizations have embraced and are using the tool. Now, in the same way that conservationists assess the natural aspects of the land—for example, the habitat, water, and biodiversity—they can also assess who will most benefit from having new open space nearby.

ML: What are some examples you can point to that are prioritizing environmental justice communities in their land conservation efforts?

JT: I work a lot with Mass Audubon, and I have been very impressed with their emphasis on protecting nature for all people in the state of Massachusetts. This includes establishing new nature preserves in Environmental Justice communities, for example in Lowell, Chelsea, and Boston. And building wheelchair accessible trails (known as All Persons Trails) at their wildlife sanctuaries across the state. And ensuring that their nature camps for children are accessible and affordable to kids from all over the state. I’ve also been pleased to see that equity in access to protected land is increasingly showing up on applications for private and public funding for new protection.

“We found that households in census tracts in the lowest income quartile tend to have access to just half as much protected land as those in the highest quartile.”

ML: Your work at the intersection of communities and conservation is so important not just for changing the narrative, but also for providing a way forward. What is on your mind for the future, and what are you working on now?

JT: Today we discussed several of the social outcomes of land protection in New England. I hope that next time we speak, we can discuss the ecological outcomes, which I’m currently working on. We’re seeing that, just like with social outcomes, there is strong variation in how different types of protection influence ecosystems. For example, state parks produce different ecological conditions than conservation easements. We’re also untangling “selection effects” (where sites chosen for protection are ecologically distinct from unprotected land) from “treatment effects” (which are the ecological changes caused by the protection itself). Gaining a better understanding of these differences will hopefully enable conservationists to apply the most effective tools to achieve their desired outcomes.

One specific example is a project recently funded by the EJK Foundation to work in collaboration with the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) and Our Climate Common to evaluate the potential efficacy of alternative conservation mechanisms for protecting the remaining old-growth and late successional forests in Maine, which have recently been mapped by Hagan et al.

ML: The social and ecological outcomes are both essential considerations for advancing integrated approaches to land protection. Thank you for walking us through this body of work, and I look forward to learning more in our next conversation.

Jonathan Thompson presenting at a recent RCP Network Gathering. Photo courtesy of Highstead Foundation

Dr. Jonathan Thompson is the newly appointed Director of the Harvard Forest, a 4,000-acre research and educational center of Harvard University located in north-central Massachusetts. His research focuses on long-term and broad-scale changes in forest ecosystems, with an emphasis on quantifying how land use—including harvest, conversion, and land protection—affects forest ecosystem processes and services. He also leads the New England Landscape Futures project, which collaborates with diverse stakeholders from throughout the region to build and evaluate scenarios that show how land-use choices and climate change could shape the landscape over the next 50 years. Jonathan holds a PhD in forest ecology (2008) and an MS in forest policy (2004) from Oregon State University along with an undergraduate degree in forestry from UMass.

Marissa Latshaw works with mission-driven organizations to build empathetic and inclusive communication strategies that inspire action. She is the publisher of From the Ground Up and co-coordinator of the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities initiative, working with partners throughout New England to help bring a more holistic, integrated approach to land conservation. Marissa resides in Connecticut where she’s always up for a walk in the conservation area adjacent to her home.