Power from the Sun

Hope in a Shattered World

Editor’s Note: Bill McKibben is no stranger to the climate conversation, nor to From the Ground Up readers. He has been a steadfast voice on climate change since the 1980s when he published The End of Nature. He continues to write constantly on the topic for The New Yorker and other magazines, and this year published Here Comes the Sun. Together with Third Act, he is organizing Sun Day on September 21. We interviewed him in our first issue, and we are grateful to have his insights again here. – Liz Thompson

It has been the most brutal six months for the American landscape in the history of the Republic.

Since Donald Trump’s inauguration, his administration—composed largely of people who spent their lives “extracting resources” or lobbying to make that extraction easier—has managed to undo a great deal of the hard work of generations of environmentalists. They have undone the roadless rule, which dates back to the Clinton administration, and they have mandated steep increases in the cut on national forests—the newly passed budget bill will double the timber harvest over the next nine years, taking us back to 1990 levels. They’ve gone to work rescinding habitat protection for endangered species, and they’ve opened up millions of acres in Alaska to drilling and mining.

All of these initiatives will be fought in court, of course, and some of them will be easier to realize than others. It’s not clear, for instance, where the mill capacity to handle vast increases in timber cuts will be found. But on every front, a fast-moving ideologically committed administration is moving to loot the 50 states in the guise of an “energy emergency” and a “timber emergency.” The ability of the administration to function in emergency mode—to ignore or suspend time-honored practices of consultation and comment—has left the environmental community squarely on the back foot, clinging to practices that may have no real purchase in this new world. That’s especially true since it’s not clear that the Supreme Court won’t go along with these push-the-envelope tactics; they’ve systematically empowered the executive branch over the last few years and show no sign of stopping.

Wildfire smoke creates an eerie sky in Maine on August 4, 2025. Photo © Karen Leavitt

But of course that’s not the only thing that’s happening to the American landscape and the global landscape. We’re also seeing an accelerating heating of the planet that is producing the by-now-expected freight of fire and flood. We understand more about what’s going on all the time: New data shows a tripling of extreme summer weather events, for instance, because the melt of Arctic ice is cutting the temperature differential between the equator and the poles, and is thus throwing the jet stream out of its customary patterns. Meanwhile, ocean temperatures continue at all-time highs, and the resulting storms are increasing coastal erosion even as sea levels continue to rise. And, just to add a little fear, the latest research shows that the great Atlantic currents have begun to flicker and falter, raising the prospect of radical and desperately fast changes in both temperature and the height of the ocean. It’s possible you won’t have to pay attention to any of this much longer though—the Trump administration is also relentlessly cutting the budgets of every agency that monitors these things, and shutting down the feeds off the satellites that until now have provided us with a snapshot of our impacts. We are choosing to bury our heads in the hot sand.

Against all this there is, as far as I can tell, precisely one hopeful trend on the planet, and that is the very rapid rise of the capture of energy from the sun and wind. Since the climate crisis is caused mostly by burning fossil fuels, anything that allows us to dispense with them is helpful—and there’s a lot of that dispensing beginning to happen. In California, for instance, enough solar panels and wind turbines have gone up in the last few years that the world’s fourth largest economy now generates more than 100 percent of its power from renewable sources for long hours almost every day. And enough batteries have been installed on the grid that when the sun goes down they are running much of the Golden State off stored sunshine all evening. As a result, California is using 44 percent less natural gas to generate electricity this year than it did in 2023. That’s a big number, big enough to matter in how hot the planet eventually gets.

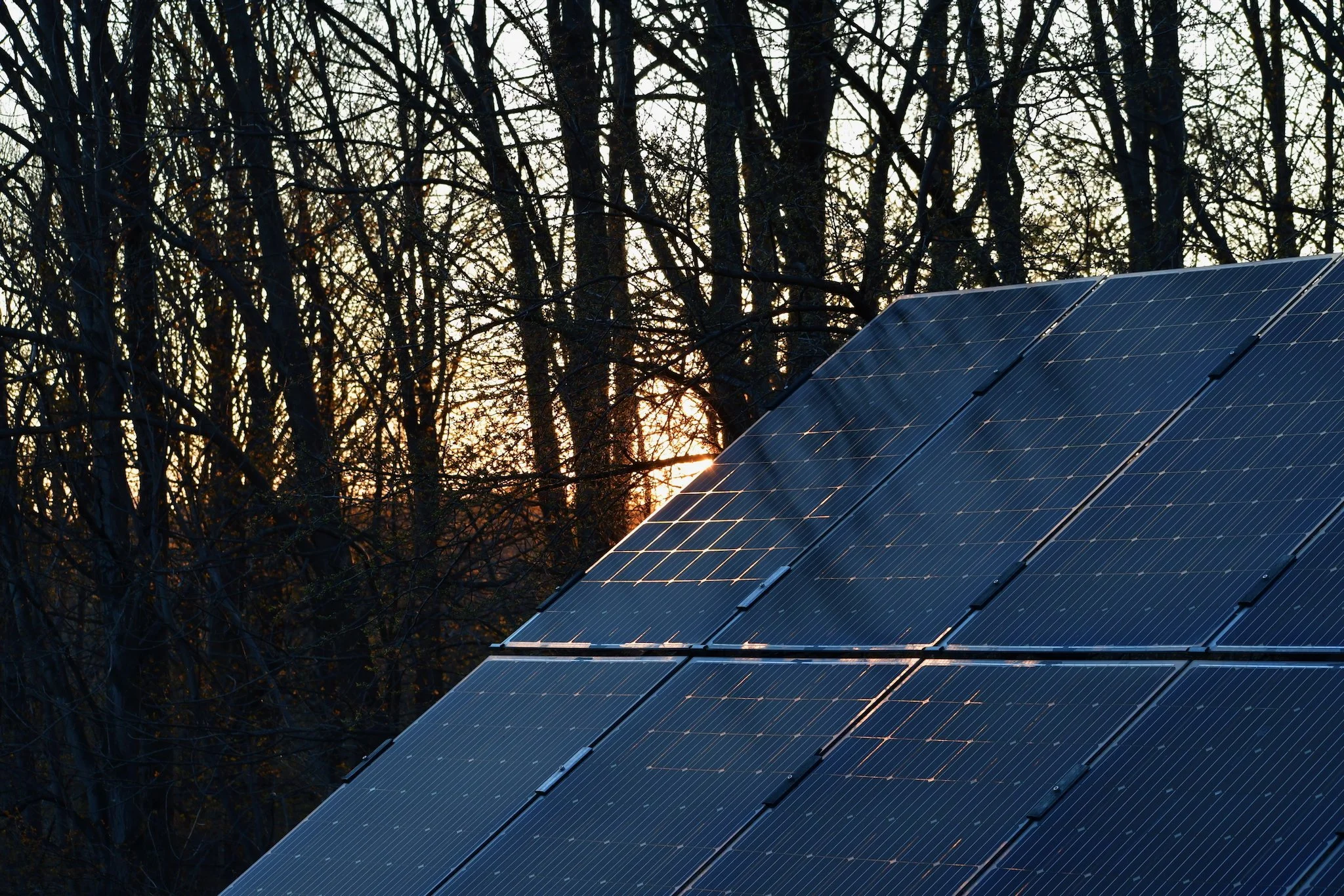

An increasing number of private homeowners are joining the ranks of solar energy producers. This array provides more energy than is needed for the single-family home it serves. Photo © Liz Thompson

This new hotel, opened in 2025, has a roof covered with solar panels. Photo © Liz Thompson

It’s not without cost—the solar arrays need to be sited somewhere—they take up land. They require minerals to work; the mines take up land, too. But the mining is minimal compared to what the solar arrays replace. A new study last year from the Rocky Mountain Institute found you’d need a smaller volume of mining to extract all the minerals needed for an energy transition through 2050 than the volume of coal mined last year alone. Here’s a way to visualize this: 40 percent of all the ship traffic on our planet simply carries coal, gas, and oil back and forth across the planet to be burned to provide energy, a job the sun is willing to do for free. As for the land taken by solar arrays, it’s not, according to Stanford’s Mark Jacobson, more than the footprint of oil and gas on our landscape. And when it’s done right, it can be a blessing. I’ve spent time in several Vermont solar farms that have been sown with pollinator-attracting plants between the rows. The number of insects soars by orders of magnitude over a standard-issue corn field; species long thought extirpated have somehow found these patches of plants and have resumed standard operations!

This solar array in Morrisville, Vermont “features pollinator plantings to offer a lower maintenance ground cover while also providing critical habitat for the dwindling number of native pollinators which are critical for our future food supply needs. The project is sited on a former corn silage site.” – Encore Renewable Energy Lawrence Brook Solar. Photo © Liz Thompson

But again, nothing comes for free. My state of Vermont has long had, for instance, a de facto moratorium on wind power. We don’t need a turbine on every mountaintop, but we do need them on some: I continue to hope and work for a few atop Middlebury Gap, where I live.

Ridgetop wind turbines. Photo © Liz Thompson

So for me, the tasks of the moment are twofold. The first task is to play what defense we can against the egregious steps the administration has undertaken: At Third Act, where we organize people over 60 for action on climate and democracy, we’re good at everything from fighting elections to intervening in Public Utility Commission proceedings. The second task is to play offense in the one place where we’ve got some momentum: clean energy.

Members of Third Act will participate in Sun Day on September 21. Photo courtesy of Third Act

That’s why we’re coming together across the movement on September 21—the fall equinox—for what we’re calling Sun Day. It’s a celebration of the possibilities for clean energy, with the goal of making it clear to people this is no longer “alternative energy,” but instead the obvious, common-sense, and beautiful way forward. Imagine a planet where we cease combustion and instead rely on that large ball of burning gas hanging a convenient 93 million miles away. It could transform, among other things, our ruinous politics. The sun is an energy source that can’t be hoarded, and that you can’t fight wars over. Putting it to good use would change the nature of both power and power, if you see what I mean.

Thousands of people have contributed drawings to celebrate the sun and Sun Day. Photo courtesy of sunday.earth

Bill McKibben. Photo courtesy of Bill McKibben

Bill McKibben is a contributing writer to The New Yorker and a founder of Third Act, which organizes people over the age of 60 to work on climate and racial justice. He founded the first global grassroots climate campaign, 350.org, and serves as the Schumann Distinguished Professor in Residence at Middlebury College in Vermont. In 2014 he was awarded the Right Livelihood Prize, sometimes called the “alternative Nobel,” in the Swedish Parliament. He’s also won the Gandhi Peace Award, and honorary degrees from 19 colleges and universities. He has written over a dozen books about the environment, from his first, The End of Nature (1989) to the just-released Here Comes The Sun (2025).