Farmland Access

Where Farms, Food, and Communities Come Together

Access to farmland is at the heart of an integrated vision of conservation for New England.

This might not seem obvious at first glance. Little more than five percent of New England is cropland and pasture; some 80 percent is wooded. The pre-European landscape was even more heavily forested. One could make the case that conserving forest is what really matters, and that conserving New England farmland is a sentimental sideshow or a distraction.

But a growing number of conservationists are seeing the importance of farmland in the regional conservation picture. How we grow food is a fundamental part of our relationship with Nature: It is where industrial-scale production does profound environmental and cultural damage. It is also where we can build community strength and ecological resilience. How we grow food has a far larger impact, for good or ill, than the small percentage of the landscape it occupies.

Scallion harvest at Indian Line Farm in South Egremont, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of the Berkshire Community Land Trust

For the past half-century, conservationists, food advocates, and farmers have worked to arrest the long slide of New England farming, to keep from losing any more ground and to build more sustainable ways of farming into the future. To counteract ongoing threats to the globalized food supply chain, including climate change and a whole raft of other environmental and social degradations, A New England Food Vision looks to the day when we could, with a modest increase in farmland, sustainably grow up to half of our food within the region.

Conserving New England farmland is expensive. Making that land available for more people who want to farm—especially younger people and people of color—is even more expensive. Yet conserving farmland and making it available are both essential if we are to realize the full benefits of local farming. The point isn’t just to increase regional food production—it is to increase the diverse range of people who can build more connected food systems for their communities. It is to put more people on the land to care for it—to provide biodiversity and other ecological benefits, alongside greater capacity to grow food.

“How we grow food is a fundamental part of our relationship with Nature: It is where industrial-scale production does profound environmental and cultural damage. It is also where we can build community strength and ecological resilience.”

This is a political matter, as much as an economic one. Over the past few years, increased federal funding began flowing to help support state policies to conserve land and improve the health of food systems, even in the face of relentless economic forces driving in the other direction. Now, with a new administration, much of that federal support has been cut off—how completely and for how long, we don’t yet know. Carrying on the work of protecting land with the resources still available to us is an important way to stay grounded.

Building more democratic, equitable food systems is an important way to build political power. Photo courtesy of Soul Fire Farm

But more than that, protecting and building more democratic, equitable food systems—while keeping in the forefront the questions of who has access to land, and who has access to healthy food—is also an important way to build political power. Ultimately, the healthy New England forests, farms, waterways, and communities many are working to create cannot be achieved in isolation. These initiatives will need sustained federal policy and support. But conversely, that support can only be secured by building a strong constituency, stretching from cities to the countryside, “from the ground up.” Connecting more farmers to land is one way to accomplish that.

The methods for brokering these connections range widely: from acquisition of agricultural conservation easements designed to make land purchases more affordable, to short-term land access opportunities and long-term technical supports provided by incubator farms and farmer training organizations, to simpler strategies that center on finding new partners and allies to support farmers in their search for land tenure. See Regional Profiles of Farmland Access in this issue. These are all tools available in our collective toolbox, but, as with any complicated project, it’s rare that a single tool can get the job done.

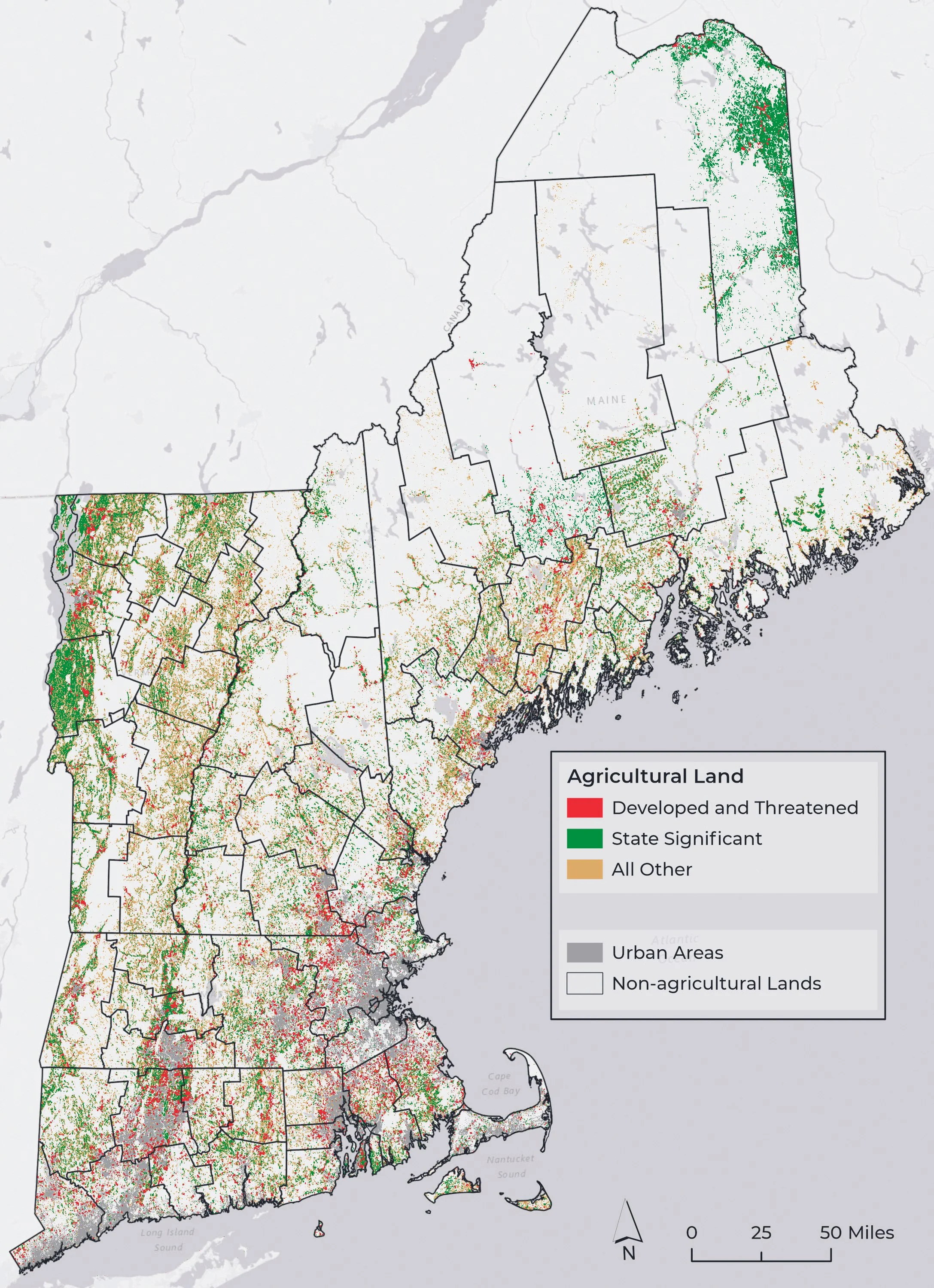

The effort to build a more equitable food system and to ensure its viability runs headlong into several powerful market forces. Beyond the challenges farmers face in attempts to make a decent living, the demand for land continues to push the conversion of fields and forests across the region. As the next generation of farmers looks to get started, the parcels best suited for agriculture are more likely to end up as a backyard, a subdivision, a solar array, or a field owned by the larger farm across town. Newer farmers, with limited assets and without an existing business to leverage, typically have fewer resources than other competitors on the open market. As a result, farmland in the region continues to be irreparably lost to other uses.

American Farmland Trust publishes spatial projections for farmland loss in New England through 2040. The projects include models for “Business as Usual,” “Runaway Sprawl,” and “Better Built Cities.” National and state-level data are available to explore through Farms Under Threat: Choosing an Abundant Future. More recent analysis initially points toward national farmland loss trends that outpace even the “Runaway Sprawl” projections. Farms Under Threat: A New England Perspective

“Protecting and building more democratic, equitable food systems—while keeping in the forefront the questions of who has access to land, and who has access to healthy food—is also an important way to build political power. ”

Throughout this issue of From the Ground Up, we offer examples of local action and targeted projects that recognize the need to protect ecosystems and landscapes from existential threat, while directly boosting our ability to feed ourselves. In previous issues, we have reflected on our responsibility to manage forest resources by both expanding land protection and making significant changes to our stewardship practices and consumption patterns. The same commitments should be made for farmland and our food system. Expanding the breadth and diversity of farmland access work across New England has the potential to provide communities—human and wild, urban and rural—with the integrated and balanced landscape that can sustain us all moving forward.

Brian Donahue is Professor Emeritus of American Environmental Studies at Brandeis University, and a farm and forest policy consultant. He co-founded and for 12 years directed Land’s Sake, a nonprofit community farm in Weston, Massachusetts, and now co-owns and manages a farm in western Massachusetts. He sits on the boards of the Massachusetts Woodland Institute, the Friends of Spannocchia, and Franklin Land Trust. Brian is author of Reclaiming the Commons: Community Farms and Forests in a New England Town (1999); The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord (2004) and Slow Wood: Greener Building from Local Forests (2024). He is co-author of Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities (2017) and A New England Food Vision (2014).

Alex Redfield is the Policy Director for Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities. On the farm, in state government, and in conservation policy circles, his work for the past 20 years has centered on supporting a just transition of New England’s landscape toward an equitable future. He lives in South Portland, Maine.