Wolves in the West, Wolves in the East

Views from Wyoming

Editor’s Note: Could wolves thrive in New England once again? Having seen them recolonize agricultural Denmark and recognizing that their population has increased over 60 percent in the past decade across highly populated Europe, I asked this question in our Winter 2025 issue. The responses were various. Brian Donahue and others say the wolves are already here, in the genes and some of the behavior of resident coyotes. Contributors Susie O’Keeffe, Walter Medwid, and John Glowa each celebrate the idea that wolves, separate from coyotes, could return as the region’s apex predator. Following Medwid’s mention of wolves in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Liz Thompson explores—through the insights of three people with experience in the West and in the East—how the Wyoming experience can inform our own thinking about wolves in New England. – David R. Foster

It was March, 1995—deep winter in Yellowstone National Park. Fourteen Canadian wolves had arrived in January and had been caged for two months to allow them to acclimate to their new environment. It was time to open the gates and set them free. By March 31, all 14 wolves had made their way into Yellowstone.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Mollie Beattie (L), U.S. Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt (C), and Yellowstone Park Superintendent Mike Finley (3rd L) carry the first gray wolf due to be released into Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming to a holding pen in the park. Photo © POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Mollie Beattie, pictured here with Bruce Babbitt and Mike Finley, was Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) from 1993 until her death in 1996. In that role, she helped to carry the caged wolves to their new home, and she oversaw their release and subsequent protection. She was a fierce defender of the Endangered Species Act, particularly its emphasis on the protection of habitat for endangered species. She knew that wolves needed to be protected, but more importantly, that they needed suitable and viable habitat.

This emphasis on habitat is now under fire from the current administration. On April 17, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration proposed a new rule that would effectively remove habitat protection from the law, greatly diminishing its influence and effectiveness.

Prior to her appointment to the USFWS, Mollie Beattie had been a leader in Vermont’s Agency of Natural Resources and a personal mentor to me in my early career. She was the first woman to lead the USFWS, and she pointed the way for women finding their places in a male-dominated world of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

In 1995, I joined the many who watched from back east with pride and fascination as Mollie released the wolves in Yellowstone. We wondered how it would play out. Would the wolves survive—even thrive—in their new home? Would people love them? Hate them? Some of both?

Thirty years later, as the wolves have expanded well beyond Yellowstone, there are many stories to tell and lessons to be learned.

Wolves travel in packs, and when they are seen by humans, they are often on a kill. Photo © Bill Sincavage

I spoke to three people who have experience both in New England and in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. How, I asked each, might wolves fare in New England, should they make their way here from Canada, as perhaps they have already begun to do? Can experiences in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem teach us anything as we contemplate this possibility in a very different landscape?

This question is not new, of course. In 2000, John Elder edited a book, The Return of the Wolf: Reflections on the Future of Wolves in the Northeast, in which four writers reflect on just this topic. Proposals for wolf recovery in the region were very active at that time, with several organizations collaborating to ponder it and evaluate the possibility. One of the writers in Elder’s book, Kristin DeBoer, formerly of RESTORE: The North Woods and now Executive Director of Kestrel Land Trust, reflected in a recent conversation that perhaps the interest in wolf recovery in the Northeast has faded since the activity of the 1990s. But in her essay, she stresses what others have said in my conversations: that cross-border collaborations will be key to any wolf recovery effort. From her essay “Dreams of Wolves:”

“We can count on one thing—wolves need to roam, in search of prey, in search of mates, in search of new lands. They will roam outside national parks, outside national borders, outside the confines of our desired wolf management areas.”

This is the experience of Yellowstone. Wolves were released there in 1995, and they have since spread throughout the region, well beyond the borders of Yellowstone, to regions of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana where laws, regulations, and land use practices vary.

In Wyoming now, for example, gray wolves are managed under several categories. As one moves southeast from the park, regulations become less strict. In northwestern Wyoming outside the national parks, they are considered trophy animals and can be taken with a permit in season. In much of the rest of Wyoming, wolves are considered predator animals and can be killed year-round without a permit.

In much of Wyoming, wolves are considered predatory animals, and can be harvested year-round without a permit. The taking must be reported to Game and Fish within 10 days. Image courtesy of Wyoming Game and Fish

Much more recently, in 2023, wolves were released in Colorado. In early 2025, two of these wolves wandered into Wyoming and were killed by authorities due to livestock predation.

How do these facts influence our thinking about wolves in the Northeast? Can they thrive? Is there enough habitat? How would they be received if they were present beyond the few sightings reported by the Maine Wolf Coalition?

The three interviews that follow have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Interview with Naomi Heindel

Naomi Heindel is Executive Director of North Branch Nature Center in Montpelier, Vermont, and is a born-and-raised Vermonter. In researching the connections between the Yellowstone experience and the possibility of wolf reintroduction in the Northeast, I came across this article written by Naomi in 2015, remembering the 20th anniversary of the introduction, describing Mollie Beattie’s role, and citing some of the positive trophic effects of wolves returning to the landscape. Naomi taught at Teton Science Schools in Wyoming for several years, and though she is back in Vermont now, she still has strong ties to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Liz Thompson (LT): In your work with Teton Science Schools, and in your interactions with Wyoming residents and visitors, what did you learn about attitudes toward wolves?

Naomi Heindel (NH): It was one of the most polarizing things I’ve ever seen. I’ve never really experienced an ecological issue being that polarizing. Maybe fire in California when I was living there. And then wolves in Wyoming. And now it’s trees here in the Northeast. I’ve also never lived in an ecosystem where wildlife play such a critical and central role. It’s amazing how central large megafauna are to anyone’s life when you’re in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Are the elk migrating? Are there moose on the road? Can you get to your car? Is the whole town out looking at a mountain lion somewhere? Are you a hunter? It’s just so central to everyone’s lives.

In terms of wolves specifically, I saw polarization and politicization. What you do for a living, your background, and your family history all really affect how you approach this issue. If you’re a rancher, you’re coming into it with one set of views, and if you’re an environmentalist working at Teton Science Schools, you’re coming in with another set of views. I don’t think those groups have much ability or interest in talking to each other. And then you’re talking across this complicated history playing out in a huge area. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is the largest intact ecosystem in this country, and it is incredibly complex.

LT: In your 2015 article, you referenced another article that described some of that complexity, and the ways in which wolves affect ecosystems broadly—that stream systems, for example, have recovered much of their natural vegetation since wolves were reintroduced and reduced elk populations. What is your current thinking on this?

NH: “Wolves Change Rivers” is the article you’re referring to. It was exciting when that came out, but some of it was later debunked. It turns out it’s not that clear. It is a complicated picture. Yes, trophic cascades exist, but it’s not as simple as “wolves come back, elk are reduced, willows grow, and the river is suddenly cold and healthy again.” I think there had to be some relearning and some humility on the side of the environmentalists to say, OK, we jumped on that bandwagon really fast. There are some people who are still holding strong to that idea and won’t let go of such a beautiful, romantic, simple picture. That was a wonderful story to teach kids and to tell. Wouldn’t it be nice if that were the case? So I had to work through this and learn to tell the story in a rigorous, honest way.

A late March visit to Horse Creek near Dubois, Wyoming. Wolves are seen here regularly. The stream bottoms are lush with willow, coloring up with the increasing sun. Photo © Liz Thompson

Healthy willow buds along Horse Creek. Photo © Liz Thompson

LT: So, perhaps the story isn’t as simple as we’d like. Perhaps the reintroduction of wolves in Wyoming doesn’t have a happy ending with cool streams and people living in harmony with wolves. But has it, in your view, been successful? And if so, could that success be translated to the Northeast?

NH: When I think about success, it’s all about fully functional habitat. Is there enough habitat here? And I wonder more generally about conservation in the Northeast. What is its future in light of all the divisiveness and polarization that we are seeing? One thing I’m sure of: For wolf recovery to be successful here, we would need broad coalitions and cooperative management, to ensure that wolf-human interactions are more positive than negative, and importantly, that the habitat is viable.

For Mollie Beattie, it was also all about habitat. That was what the Endangered Species Act was for, in her view. What does success look like for the Endangered Species Act? I don’t think we’ve answered that question honestly, and that’s where I wish I could pluck Molly back, and ask, “OK now what?”

Interview with Sean Beckett

Sean Beckett, a Vermonter, is Program Director at North Branch Nature Center. Like Naomi Heindel, Sean worked for several years with Teton Science Schools. He was, primarily, a wolf guide.

Liz Thompson (LT): You led wolf tours. Who were your clients? Who wanted to see wolves?

Sean Beckett (SB): I led expensive week-long or multi-week ecotours, mainly for wealthy folks, many retired or nearly so. And then there were day trips or shorter trips, accessible to more folks, ranging from families that were coming to visit parks and just wanted to see and learn what they could see, all the way to folks like retired hedge fund managers who wanted a shorter trip in the hopes of encountering wildlife.

We were always looking for everything, not just wolves. Our strategy was to go to the right place at the right time and just see what would unfold. Sometimes wolves would unfold. And of course when you’re positioned in the northern range, you’re really trying to target wolves, and you know where and when to look.

LT: What did you learn about people who don’t like wolves?

SB: I had an interesting experience once. There was a cattle rancher convention that was held in Teton Village, and somehow we got hired to take them out on a wildlife watching tour. I thought, “Oh, this is perfect. I have all these ranchers trapped in a van with me. I can ask them whatever I want.” And so we got talking. There was a lot of the typical narrative that you hear from the anti-wolf side. “They’re killing all the elk.” “They’re chasing our cattle around.” “They’re making it more difficult for us to sleep at night.”

I could really feel some compassion for that last comment. Whether or not one supports the idea of being able to rent your cattle out on public lands for huge subsidized prices, these people depend for their livelihood on turning a couple hundred head of cattle out into a grazing space, leaving them there, and then coming back and hoping that they’re alive when you need to collect them. I don’t think I would sleep very well at night either, knowing that even though it’s a small chance that a wolf would kill one of my cattle, it’s still a very real chance.

Ranchers in Wyoming graze their cattle, horses, and other domestic animals on public lands. This is near Whiskey Basin in Dubois, where wolves are seen regularly. Photo © Liz Thompson

Other than that experience in the van with the ranchers, I’ve heard the same things: “They’re eating all the elk.” “They’re eating all the cattle.” “These are government wolves that we didn’t ask for.” “These are Canadian super wolves that aren’t the same species of wolf or lineage of wolf that were once here.” “They put them in the park but then of course they can’t expect them to stay in the park.”

LT: How can these kinds of reactions inform our thinking about wolf recovery in the Northeast?

SB: I think it would be a great success story to hear that wolves had reestablished themselves in the Adirondack Park or northern Maine or other places, thanks to careful stewarding of large tracts of land. I think it would be extremely problematic and counterproductive to actually go through the process of reintroducing them. The reactions to the reintroduction in Yellowstone remain incredibly hostile, even 30 years later.

However, it’s pretty well understood that had the wolf introduction not happened, wolves would likely have recolonized Yellowstone within five or 10 years on their own anyway, and that would’ve been a very different story. It wouldn’t have been the government putting in wolves at the edge of my ranch—it would have been that wolves showed up on their own, and now what do we do to protect them?

An important lesson is that if we chose to reintroduce wolves here (and there are no active proposals to do so) I think we’d burn a lot of trust and capital that’s been built up across all the years, and that might make it harder to accomplish other environmental goals.

LT: It’s been said that wolves are already here, both as wolves migrating in from the north, and, much more abundantly, in the DNA of resident coyotes.

SB: Yes, they’re already here in the form of our eastern coyotes, a hybridized wolf-coyote mix. There’s a pair across the river right here in Montpelier. We found several deer carcasses over there. This pair of coyotes has been driving deer out of the deer yard upslope in the hemlocks, down the corridor into where the snow gets deeper and it gets really hard to move around. The coyotes killed them right there, just as wolves would do.

This old hemlock forest shelters deer in winter, but coyotes drive them out to deeper snow areas for a kill. Photo © Liz Thompson

Interview with Bill Sincavage

Bill Sincavage is a professional wildlife photographer living in Dubois, Wyoming, about 100 miles southeast of Yellowstone National Park. His Boston accent and his dog’s name—Fenway—reveal his Massachusetts roots. I’ve learned a great deal from Bill about wildlife in Wyoming and surrounding areas, and also about the art of photography. I recommend following him on Instagram.

Liz Thompson (LT): From what you have seen and heard in Wyoming, what should Northeasterners know or consider when contemplating wolf recovery in our region?

Bill Sincavage (BS): It’s important to remember that wolves are big dogs, and like all dogs, they reproduce at an incredible rate. It is not uncommon to see them outside park boundaries. I’ve seen them on my wildlife camera here at my home on Jakey’s Fork [a small tributary of the Wind River], and I worry about Fenway. I see them just up the road in Whiskey Basin—25 to hundreds of animals, spread out over a large area, where it is very open. It is good to see them, but I can see both sides: ranchers on one side, environmentalists on other side.

Whiskey Basin, where wolves are seen regularly. Wyoming Game and Fish hosts conferences and retreats here, hosting training workshops for wildlife agency personnel from across the United States. Private retreats, like Bill Sincavage’s Wildlife Photography workshops, are also hosted in this beautiful location. Photo © Liz Thompson

In New England, the only area where I can see success would be northern Maine, where there are huge swaths of land and not a lot of people. The problem would be that if a half dozen wolves made their way to northern Maine, either on their own or through reintroduction, it would be OK for the first few years, but they will go hundreds of miles.

There would have to be management, as there is here. Not unregulated hunts, but some management. Wolves won’t see state borders. They have to move.

LT: Can you tell me about one beautiful or fascinating encounter with wolves?

BS: I was in the Tetons about this time of year, about four or five years ago. I was driving on a back road. A black wolf happened to cross the road. It stopped and got up, about 100 feet from me. It just started howling. It was one of those things—the wolf on the snow, by itself—one of those moments. Wow. This is not something a whole lot of people experience. He didn’t feel threatened. I didn’t feel threatened. He was collared, so it was a known animal. Still, it was neat to see. That pack has now expanded well into the Tetons, in the National Elk Refuge, where they are hunting elk.

They are beautiful to see. Hearing one howl…

Postscript

Mollie Beattie died too young. Only a year after the release of the wolves, in 1996, she succumbed to a brain tumor at age 49. She is remembered as a leader in the field of wildlife management and nature conservation. Back here in Vermont, a beautiful boreal bog is named after her, a testament to her role in securing the protection of the former industrial timberlands of the Northeast Kingdom, and the establishment of the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge.

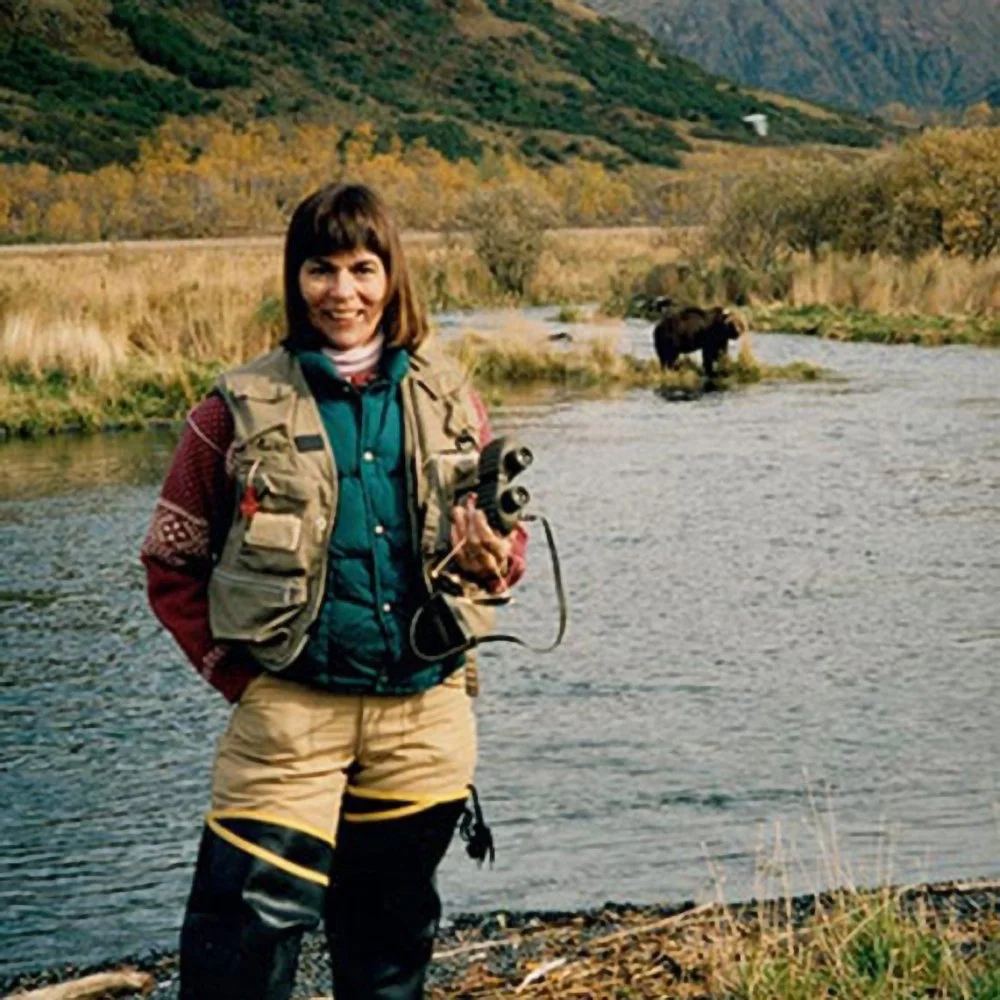

This is the official portrait of Mollie Beattie, Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 1993–1996. Naomi Heindel, family friend of Mollie, describes visiting Mollie’s office in Washington as a 10-year-old and seeing this portrait next to those of former Directors. As Naomi remembers the wall of portraits, “man in suit, man in suit, man in suit, Mollie in waders…” Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Liz Thompson, Managing Editor of From the Ground Up, is an ecologist from Vermont who has explored, photographed, written about, and helped conserve many wild places. She serves on the board of Northeast Wilderness Trust and is coordinating the 2025 Northeastern Old Growth Conference.

Naomi Heindel is Executive Director of North Branch Nature Center in Montpelier, Vermont. She taught at Teton Science Schools in Wyoming for several years.

Sean Beckett is Program Director at North Branch Nature Center, born and raised in Vermont. He worked as a wildlife guide for several years with Teton Science Schools.

Bill Sincavage is a professional wildlife photographer living in Dubois, Wyoming, about 100 miles southeast of Yellowstone National Park.