Imagining Old Growth

Clues from the Past, Clues from the Present

Editor’s Note: When it comes to understanding the oldest forests of the northeastern United States and how they compare with the forested landscape at the time of European settlement, no one has the knowledge of Charlie Cogbill. Charlie has just finished assembling his lifelong database of over 600,000 trees that were surveyed across the region in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, so I asked him to share a first perspective on the insights into old-growth forests that are emerging as he is writing up his results. – David Foster

Aerial view of Big Reed Preserve. Photo © B. Silliber, courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

In northeastern North America, most examples of “old-growth” forests are small remnants that are typically homogenous in composition, but not representative of the wider landscape. These stands are often well-documented, but are oddballs in location, environment, ownership, and history. Their restricted size also prevents them from fully exhibiting landscape-scale ecological processes, such as large natural disturbances.

The characterization of old growth based on these remaining small examples restricts the concept of “old-growth forest” in both space and time. The relevance of existing old growth to wildland designation, land conservation, restoration, climate change, or ecosystem services is therefore severely limited. A broader perspective on old growth is afforded by examining larger and more diverse areas and by examining historic conditions before widespread Euro-American influence.

Fortunately, a few exceptionally large areas in the Northeast do exist. These collectively support a variety of forest conditions that help us understand and expand on the concept of old growth. In addition, early land surveys using witness trees contain compilations of forest composition and disturbance history over the entire region.

This essay is a brief presentation of the nature of the “old-growth landscape” using data from four modern landscape remnants and witness tree data from the period preceding the virtually complete alteration of the land cover resulting from Euro-American settlement over the past 300 years.

Tionesta Natural Area looking over 1985 tornado track. Photo © Charlie Cogbill

Old-Growth Remnants: Localized Data

Four especially large and well-known areas in the Northeast support old forests with minimal human disturbance:

The Nature Conservancy’s 2,000-hectare Big Reed Reserve in northern Maine;

The Bowl Natural Area, 300 hectares in the White Mountain National Forest in northern New Hampshire;

Five Ponds Wilderness, 43,000 hectares in northern New York’s Adirondack Forest Preserve; and

The Tionesta Research Natural Area, 1,675 hectares in the Allegheny National Forest in northwestern Pennsylvania.

In each of these areas, there have been extensive studies of vegetation, as well as over two centuries of history determined from records of disturbances, land use history, dendrochronology, and stand reconstructions. Significantly, all of these places have been partially disturbed in recent years by multiple intense natural disturbances (e.g., fires, hurricanes, thunderstorm microbursts, derechos, spruce budworm outbreaks, ice storms). Despite such disturbances, each of these landscapes has maintained old-growth characteristics over broad areas, and each contains trees over 250 years old. In each case, species composition is presumed to have developed over multiple successive generations of forests (Table 1).

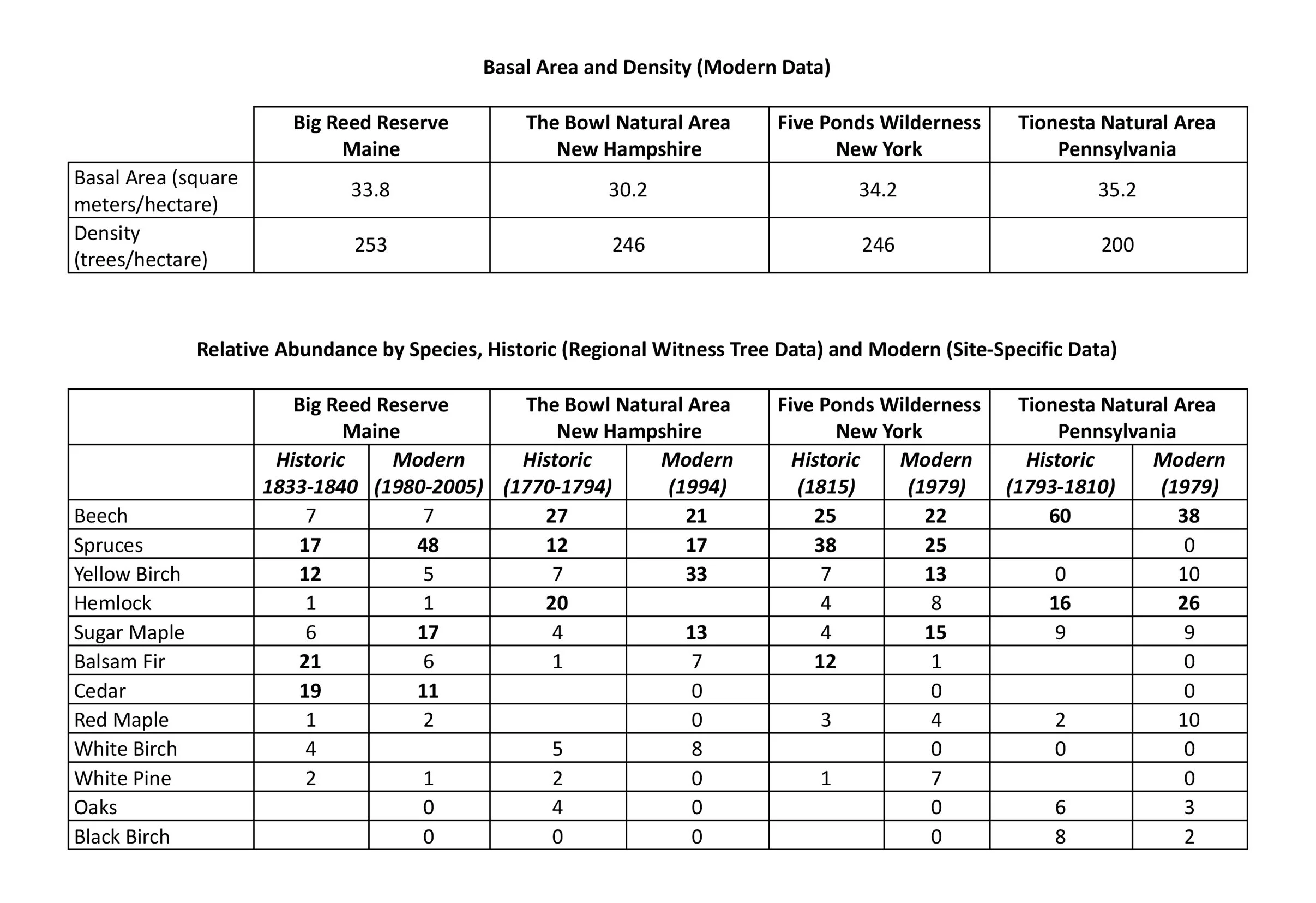

Table 1. Historic and modern forest composition of landscape-scale areas in the northeastern United States. Data assembled by Charlie Cogbill

Witness Trees: Widespread Historical Data

Historical reconstruction of the vegetation of old-growth landscapes is based on witness trees in land surveys undertaken in anticipation of Euro-American settlement. In northeastern North America, original town proprietor and land subdivision surveys ubiquitously marked and named trees at regularly located lot corners, thus making for a species-unbiased sample. I have compiled a database of over 600,000 of these marked trees from 1,657 town-sized areas (approximately 100 square kilometers) from Pennsylvania to eastern Quebec. The relative frequency of each species within the towns was then modeled across the region.

The average local composition around the four modern landscape samples is used to indicate the historic landscape in those areas 200 years ago (Table 1).

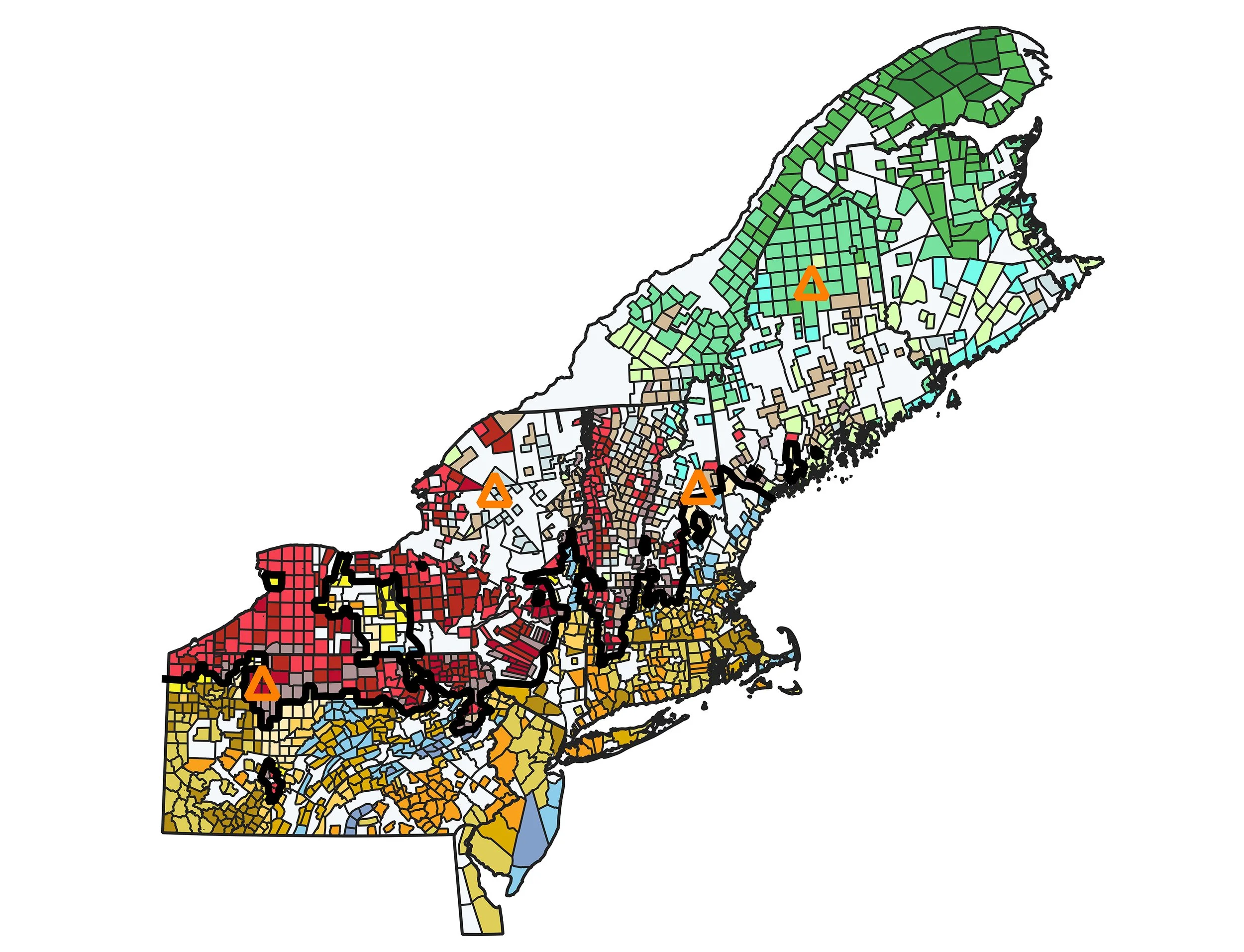

Looking at the entire region, the towns were classified into 20 clusters based on compositional similarity. Towns were statistically grouped by the relative frequency of the species. The resulting kaleidoscope illustrates a spectrum of forests across the region (Figure 1). Lacking most human influence beyond Indigenous activities, this map is a true, comprehensive picture of the region’s landscape with minimal human perturbations. This essentially defines the historic old growth.

Figure 1. Cluster analysis of species composition of 1657 town-scale witness tree samples before Euro-American settlement (ca. 1800). “Towns” with similar species composition are the same color. The black line is the separation between the last two joined units, here termed the “tension zone.” The orange triangles are the locations of the four reference old-growth landscapes. Figure courtesy of Charlie Cogbill

The Bowl Natural Area, White Mountain National Forest, New Hampshire. Photo © Charlie Cogbill

Landscape Old-Growth Composition and Structure

The composition data from the four old-growth remnants and the historical witness tree data present two lines of evidence for the characteristics of the region’s original old-growth forests at a landscape scale (Table 1). There is considerable variability in the two estimates for the same site, but pairs of historic and modern samples share most of the prevalent species, and the dominants are comparable. The differences are not surprising because the remnants are specific local landscape estimates, and the historic composition is an integration over a large area. Together the sites show a regional variation of mixed conifer-deciduous forests from spruce-cedar-northern hardwoods at Big Reed, through spruce-northern hardwoods at Five Ponds and The Bowl, to hemlock-beech at Tionesta. In general, the historic vegetation had relatively more beech and spruce while the modern landscape supports more sugar maple and birch. All of the species—such as hemlock and beech—that were abundant historically are common in older forests, while those found in low abundance–such as cherry and aspen—are characteristic of younger forests.

“In northeastern North America, most examples of “old-growth” forests are small remnants that are typically homogenous in composition, but not representative of the wider landscape.”

The forest structure of old-growth landscapes is displayed by the density and basal area of the landscape sample. All four of the modern remnants support 200 to 253 canopy trees per hectare and 30.2 to 35.2 m2/ha of stem cross-section (Table 1). Significantly, the historic data from the Holland Land Company Land of western New York (surveyed in 1798–1800 but data not displayed in Table 1) indicate a very similar structure, with an estimated density of 247 trees per hectare and a basal area of 29.8 m2/ha over its 1.3 million hectares.

Interestingly, all of these numbers are modest compared with some individual modern old-growth stands, which may have basal areas up to 42 m2/ha. The lack of superlative structure in the one historic sample described, and in the four landscape remnants, is due to the mosaic of diverse forest types and disturbance histories. The densities and basal areas are roughly equivalent to those of well-developed modern second-growth stands. Other witness tree surveys yield historic densities from 300 trees/ha in central New York to 467 trees/ha in the conifer forests in northern Maine, indicating patches of dense smaller trees in other early landscapes.

The author in the forest at Five Ponds Wilderness. Photo © Charlie Cogbill

Regional Variation

A classification of town witness tree samples displays the historic structure of the forest at a grand regional scale (Figure 1). The town-scale composition already integrates the proportion of tree species across different forest types within the town. The clusters of similar composition then define zonal patterns (associations) across northeastern North America. This map is the empirical expression of ecological regions and the potential natural vegetation, or old-growth forest types, throughout the region. This mosaic of 20 clusters falls into four broad spatially coherent associations, color-coded by type (boreal conifers are green; northern hardwoods are red; temperate pines and hemlock are blue colors; and southern sprout hardwoods are brown and orange). The zones are separated by distinct ecotones where the species proportions change across a narrow geographical distance. Very prominent is the ecotone (black line in Figure 1) between the northern hardwoods, exemplified by beech, and the sprout hardwoods, exemplified by oaks. This tension zone across the entire region results from a complete turnover of species composition within 40 km across the zone. In contrast, the same amount of old-growth change occurs over 200–300 km within the adjacent associations. Amazingly this line has not shifted in the past 200 years—mapping of modern vegetation shows the distinct transition between sprout and northern hardwoods in the same location.

Disturbance History

Major disturbances are crucial to the initiation and disruption of forest development. While less influential at the local scale due to long return times or patchy severity, intense disturbances are common in old-growth landscapes. For example, they were repeatedly observed in the four modern sites. Big Reed Preserve saw a fire in 1816; budworm outbreaks the 1810s, 1920s, and 1970s; and a downburst in 1983. The Bowl Natural Area experienced hurricanes in 1815 and 1938; a landslide and fire about 1825; and an ice storm in 1998. The Five Ponds Wilderness was disturbed by a derecho in 1995. Tionesta was disturbed by a tornado in 1985 and a derecho in 2003.

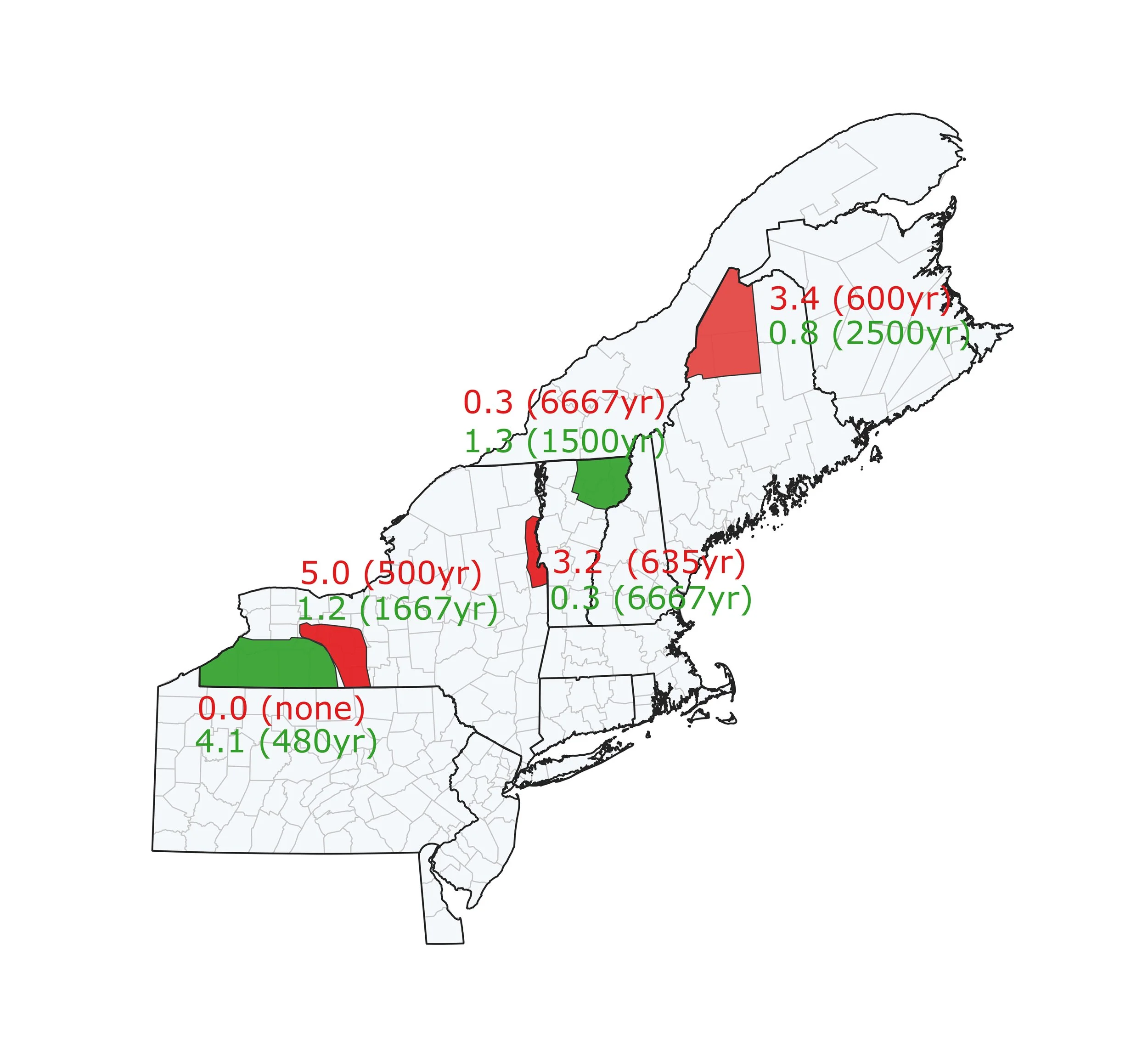

And looking at the historical data, the early surveyors noted many disturbances along the survey lines between witness trees. The proportion of the lines between witness trees with ground burned or blown down indicates severe disturbance by fire or wind. Assuming a 20-year period when such observation remained notable, the total percent divided by 20 indicates the approximate annual disturbance rate. The reciprocal of this disturbance rate is the point return time (the number of years to disturb the equivalent of 100 percent of an area, or the average time between disturbances).

In the historic landscape, fire and wind dominated the noted disturbances. Fire was prominent in northwestern Maine, the eastern edge of the Adirondacks, and the western Finger Lakes in New York. Wind dominated major disturbances in the Green Mountains in Vermont and Allegheny Plateau in western New York. Despite their common occurrence, the return time for fire and wind was much greater than the average age of the trees in these landscapes. For example, at Big Reed Pond the major blowdowns have a return time of 1,667 years, while the mean age of trees is 170 years.

Moreover, a ubiquitous background of small-scale mortality (0.5 percent to 1.0 percent per year) dominates the disturbance regime and determines the resultant age structure of the region. This means that the background mortality due to small diffuse disturbances (individual tree death, gaps) is more influential than the more obvious, but less common, intense disturbances. Thus, stand-initiating disturbance does not affect every generation, and the landscape displays a continuity of forests over multiple generations.

Historic stand-initiating disturbances in selected regions by fire (top numbers) and wind (bottom numbers). The first number is the percent of presettlement survey lines disturbed. Values range from 0.0 (no evidence of disturbance recorded) to 5.0 (5 percent of lines showing the disturbance). The second number, in parentheses, is the calculated return time in years. In red areas, fire is the predominant disturbance; in green areas, it is wind. Figure courtesy of Charlie Cogbill

Landscape old growth has both temporal and spatial facets. Witness trees provide a key model using both perspectives before the pervasive changes that followed Euro-American settlement. This widens the concept of old growth from a specific forest condition at one place and time to a consideration of its diversity and continuity. The processes occurring in this historic arena provide a powerful definition of old growth. The availability of historic and remnant old-growth landscapes is also an important baseline for comparison with modern and future forests.

Using both sources of data can provide important insights into past forests. These tools and insights can help with the identification of new areas; inform management; guide us in the creation of Wildlands; and help us predict future composition in the face of climate change.

All our thinking, planning, and conservation of old-growth forests should be done at the landscape scale, where diverse and widespread changes in the forest play out and evolve over many generations.

Presentation from the Northeastern Old Growth Conference 2025

September 17-21, 2025 | Middlebury College - Bread Loaf campus | Ripton, Vermont

View all recorded presentations from the conference.

Charlie Cogbill is an independent ecologist and long-term Associate of the Harvard Forest who specializes in understanding the history and ecology of landscapes with an emphasis on New England and adjacent New York. A preeminent expert on old-growth forests, for the past 40 years Charlie has synthesized and greatly expanded data from early surveys to reconstruct the nature of the forested landscape of the northeastern United States at colonial settlement.