From Loss to Hope

Editor’s Note: When my family and I moved to Bristol, Vermont, in 2009, the first thing we did was to read John Elder’s Reading the Mountains of Home, a love story to the landscape surrounding his home (and our new home), told through the lens of Robert Frost’s poem “Directive.” Through this volume we became familiar with the history of that fascinating landscape, from the formerly farmed, now forested, hills to the river that had, in glacial times, deposited vast quantities of gravel that were being mined all around the outskirts of the town. With his deep connection to Frost, to Middlebury College, to Bread Loaf, and to the wild landscape of the Green Mountains that surround that place, it was so perfectly fitting that John should welcome us to the 2025 Northeastern Old Growth Conference with his words and his music. This essay is a slightly edited version of his remarks. – Liz Thompson

The mountain campus where we’ve gathered today has important things of its own to say about our topic of preserving and fostering old growth in the Northeast. In the decades following the Civil War, Joseph Battell purchased 30,000 acres surrounding what is now the Bread Loaf Inn. While growing up in the town of Middlebury he had been horrified by the heedless deforestation of his home landscape. His goal in adulthood thus became protecting these cut-over ridges from further depredation. The vast tracts of land he bought ultimately became the core of a new northern unit of the Green Mountain National Forest, while across Route 125 from where we are presently meeting stand the Bread Loaf Wilderness and the Joseph Battell Wilderness Areas, established in 1984 and 2006.

Bread Loaf Wilderness. Photo © Trscavo, Courtesy Wikimedia Creative Commons License

The deep forests of today’s Bread Loaf offer reminders that the conservation movement in America has often germinated in landscapes ravaged by deforestation. This was also true for Battell’s Vermont predecessor George Perkins Marsh, whose 1864 masterpiece Man and Nature grew out of similar destruction around his Woodstock birthplace and did so much to inspire the founding of national parks and national forests, not only in the United States but also in a number of other countries. Sophisticated cartography and scientific analysis of forest ecology are both essential to conserving old growth. But the example of Bread Loaf’s ongoing recovery testifies that loss, grief, and hope are also inseparable from such an effort. Deforestation, like the climate crisis of our current moment, is not simply an external problem to be solved. It is inseparable from our American story as well as from our own daily choices and economic assumptions. Such encompassing loss requires a process of personal and cultural transformation.

The second important connection between conserving old growth and the theater in which we’re meeting is that over a period of more than four decades Robert Frost often read from his poetry at this very podium. He had been crucial to the founding of the Bread Loaf School of English in 1920 and the Bread Loaf Writers Conference in 1922, after Middlebury College inherited this land following Battell’s death. When Frost first visited Bread Loaf in the early twentieth century, there were still numerous cellar holes, as well as abandoned and slumping farmhouses and barns, in the resurgent woods near campus. The rocky soil of Vermont’s upland farms was often played out within just a couple of generations after families had so laboriously cleared their fields and built their homesteads. So many of his poems focus knowledgeably and precisely on this reversion from farms to forests.

Writers’ Conference Director Theodore Morrison, Kay Morrison, and Robert Frost outside at the Bread Loaf campus, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, August 1955. Photo courtesy of Middlebury College Special Collections, Creative Commons License

The human relics in the woods in no way lessened the forest’s appeal for the poet. Like his poetic forerunner Wordsworth, he was strongly drawn to haunted landscapes, in which an apparently vanished era still spoke through such traces. Many of Frost’s poems, including “Something for Hope” and “Directive,” evoke this stately, slow dance of old growth and new growth within a long cycle of reforestation. Coming to view his own mortality within this encompassing cycle of disappearance and return seems to have consoled Frost, allowing him to keep writing with vigor way up into his 80s.

George Perkins Marsh frequently referred to the water circulating within healthy woods as at once their ultimate source of strength and their most important product. As Marsh noted at one point in Man and Nature, “reclothing the mountain slopes with forests and vegetable mould” will also restore “the fountains which [nature] provided to water them.” In poem after poem, Frost similarly focused on the way in which the annual cycle of water within the woods of this dramatically seasonal region represented, and also sustained, the forest’s wholeness and health. So in thinking further about old growth and new growth, crisis and hope, let’s pause over Frost’s poem “Hyla Brook.” (The term “hyla,” by the way, was in Frost’s day an inclusive term for the tree frogs choiring overhead as winter turned to spring in the Vermont woods.)

By June our brook’s run out of song and speed.

Sought for much after that, it will be found

Either to have gone groping underground

(And taken with it all the Hyla breed

That shouted in the mist a month ago,

Like ghost of sleigh-bells in a ghost of snow)—

Or flourished and come up in jewel-weed,

Weak foliage that is blown upon and bent

Even against the way its waters went.

Its bed is left a faded paper sheet

Of dead leaves stuck together by the heat—

A brook to none but who remember long.

This as it will be seen is other far

Than with brooks taken otherwhere in song.

We love the things we love for what they are.

In this dried-up seasonal brook, Frost found a microcosm of the seasonal cycle encompassing both his own life and that of the thickening Vermont woods. A meandering transect of partially embedded stones plastered with fallen leaves, observed on a day long after the tree frogs had ceased their singing, might have been experienced as a desolate picture. But the poet’s taste for haunting, as captured in that gorgeous line “Like ghost of sleigh-bells in a ghost of snow,” makes it instead a precious emblem of continuity in the life of the forest. The snow had lain on the ground in drifts until its April melting temporarily replenished a seasonal brook and enlivened the tree frogs with their jingling chorus of “Love! Quick! Over here!” What Frost understood, though, was that the water doesn’t ever really go away—even in this present, alarming summer of drought. Rather, it sinks down out of sight into the water table and awaits the next turning of the circle.

“Deforestation, like the climate crisis of our current moment, is not simply an external problem to be solved. It is inseparable from our American story as well as from our own daily choices and economic assumptions.”

Frost was not only distracted from his personal anxieties by the ever-changing life of nature; he was also drawn into a circuit of energy that sustained him in the face of his advancing years. Perhaps my deepening appreciation for “Hyla Brook” over the past summer relates to my own experience of the aging process. As my wife, Rita, and I encounter illness and diminished mobility, we have found equanimity in the counsel of Buddhism and Stoicism alike to love the life one has. But this is more than a posture of quiescence. The final line of Frost’s poem brings out the dynamic aspect of such acceptance. “We love the things we love for what they are.” What they are is inseparable from what they were as well as from what they will become. Loving the stilled brook in such a way takes the wholeness of its circuit into one’s heart, helping us feel at home in an ever-changing forest and carrying us forward in the world beyond our human separateness.

A nearly-dry streambed on a field trip in the Bread Loaf Wilderness following the conference. Photo © Sara Hart

Joanna Macy offers these encouraging words to readers of her book World as Lover, World as Self, “Let there be serenity in all your doing. Even while putting forth great effort, you are held within the web of life, within flows of energy and intelligence far exceeding your own.” Though the determination to conserve old-growth forests may begin in grievous loss, it is sustained and strengthened by imagining the natural wholeness which is at once our origin and our hope. This is the spirit of humility essential to conserving old growth and celebrating rewilding. It manifests in hope that begins in facing our grief and grows into action on behalf of what we love.

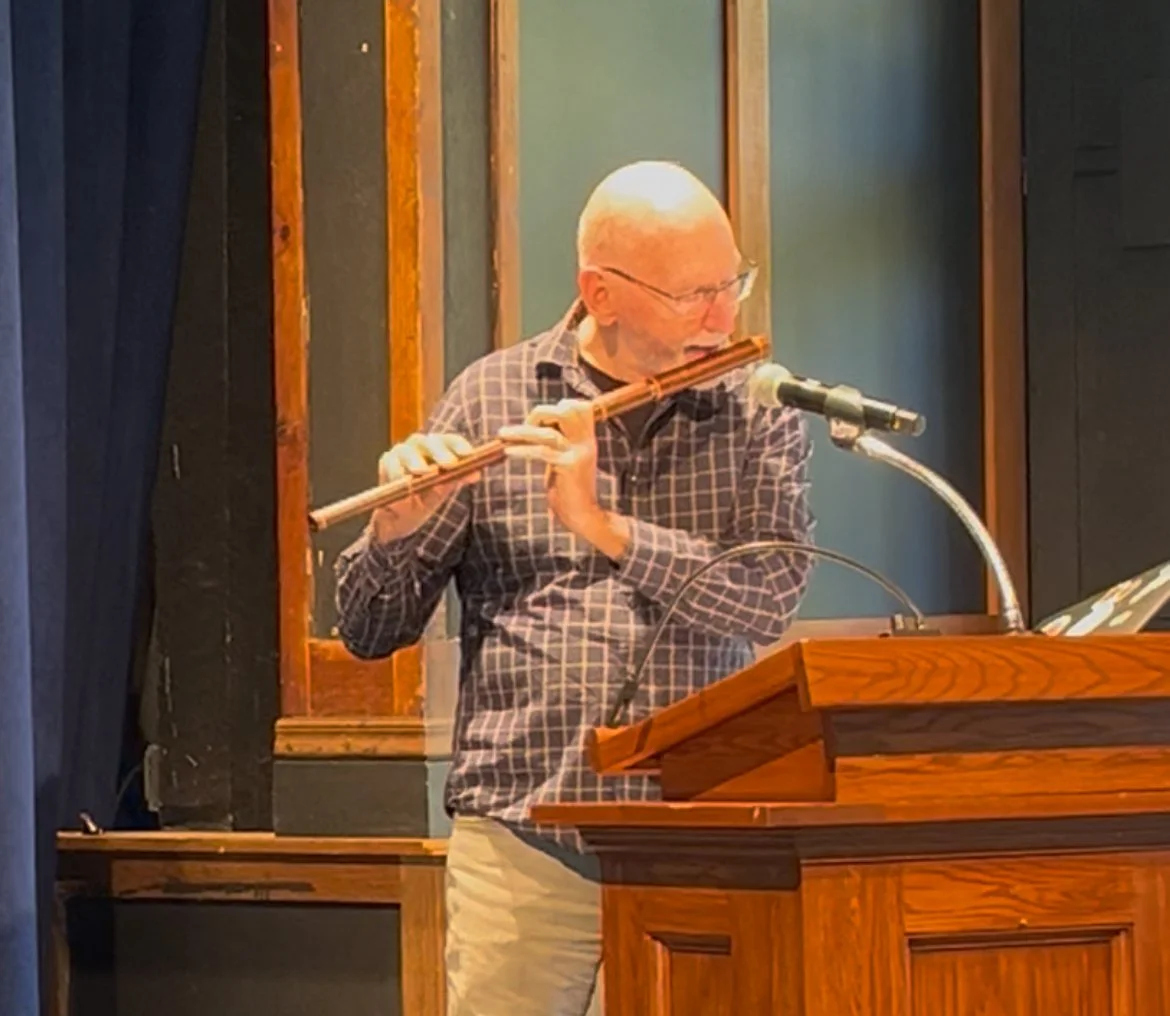

The author plays Liz Carroll’s tune “Island of Woods” on his wooden flute at the beginning of his talk. Photo © Marissa Latshaw

Presentation from the Northeastern Old Growth Conference 2025

September 17-21, 2025 | Middlebury College - Bread Loaf campus | Ripton, Vermont

View all recorded presentations from the conference.

From 1973 to 2012 John Elder taught at Middlebury College as well as in numerous summer programs at Bread Loaf. The Thoreauvian lineage of nature writing, Romantic and contemporary poetry of the earth, and the classical poetry of China and Japan were central to many of his classes. Beginning with Reading the Mountains of Home (1998), each of John’s last four books has combined discussions of poetry, descriptions of the Vermont landscape, and memoir. His days in retirement are often organized around the impossible but irresistible challenges of learning to read Du Fu in Chinese and to play Ireland’s uilleann pipes.