Managing for Biodiversity and Climate Mitigation

An Integrated Approach Guided by History

Editor’s Note: David Foster’s long history of scholarship in landscape history qualifies him uniquely to address this conundrum—that we humans, facing the crises of biodiversity loss and climate change, along with all the challenges to human health arising from these, are trying perhaps too hard to make things better, not seeing that “making things better” might, in some cases, make things worse. Foster weaves in the integrated approach to land conservation and the historical perspective of Henry Thoreau—who lived in a time of huge landscape transition—to make his pitch that we be thoughtful about our actions, and that we look to history for guidance. – Liz Thompson

“Historically, the vast majority of Vermont’s landscape was old forest, and it is the original habitat condition for many species. The state’s native flora and fauna that have been here prior to European settlement are adapted to this landscape of old, structurally complex forest punctuated by natural disturbance gaps and occasional natural openings such as wetlands or rock outcrops… The closer the target is to the historic old forest condition, the greater the likelihood that the landscape will support all of Vermont’s native forest species and fully provide the forest’s ecological services.”

Vermont Conservation Design Part 2. Natural Communities and Habitats. Old Forests

“The simple act of letting our trees grow helps mitigate the effects of climate change… Forest reserves… store the greatest amount of carbon... For those reasons alone, forest reserves should remain protected and be expanded.”

Massachusetts Audubon Society. State of the Birds 2017

“This sets the stage for a conservation dilemma which is playing out in many parts of the Eastern U.S. and Europe. We have…disturbance-adapted species that are associated with modern anthropogenic disturbance but not with any readily defined natural disturbance…[For example] although firelane management [in state forests] has no pre-colonial analog, it has created large rare plant populations [that]…warrant conservation… Annual fall mowing has maintained this habitat for five rare plant species for nearly a century.”

Gretel Clarke & William Patterson 2007. The Distribution of Disturbance Dependent Species

To stanch biodiversity losses, conservationists protect intact forests and allow natural processes to flourish. Letting forests age replenishes rare old-growth forests and associated biodiversity, and it mitigates climate change as carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is stored in living and dead plant material.

At the same time, state and federal agencies support conservation partners to clearcut, brush-hog, burn, and deforest expansive areas to support non-forest species.

Clearcutting by the Division of Fish and Wildlife and Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program on the Muddy Brook Wildlife Management Area in Massachusetts in 2020. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Forest Watch

What motivates conservationists to promote ancient forests while embracing clearcutting? Might there be a better, more historically grounded and practically sustainable way to support the openland habitats and species that many love than destroying and thwarting forests?

To begin, let’s confirm that forest destruction in New England for conservation is widespread; well funded; and endorsed by federal and state agencies, wildlife and hunting groups, Natural Heritage programs, and naturalists. Broadly, these efforts seek to retain 10–20 percent of the region in openlands and young forest.

Former pasture regularly burned by The Nature Conservancy as one of the “native” grasslands on Martha’s Vineyard. Photo courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

Massachusetts is a leader in this effort. Ambitious state goals seek to double the extent of non-forested habitat, and since 2022 the Division of Fish and Wildlife provided over $2 million toward this goal for projects in 50 towns involving private landowners, land trusts, municipalities, and all major conservation groups. In Connecticut, a Bureau of Natural Resources brochure extols clearcuts “to make sure that forests are sustainable and provide the most benefits for wildlife,” asserting that in comparison to natural disturbance such as beaver activity or hurricanes, “clearcuts are more predictable and controlled avenues to healthy forests.” Arguing that “cutting a forest is a way of mimicking nature,” the brochure recommends increasing young forest statewide to 20 percent of woodlands. Vermont Conservation Design recommends that to “meet the needs of wildlife…[landowners should]…maintain 8 to 10 percent of their property in shrub or young forest cover.” In addition, three large regions across Vermont are identified for enhancing anthropogenically created grasslands. In Maine, where less than three percent of the industrially managed northern half of the state supports mature forest, the State Wildlife Action Plan seeks to increase early successional habitat in southern regions. Forest destruction for conservation is widespread in New England.

Brochure produced by Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) to promote management for biodiversity. Photo courtesy of Connecticut DEEP

So, what motivates this expensive, environmentally damaging, and fossil fuel-intensive battle against forests and natural reforestation? Biodiversity is the primary driver, including the promotion of abundant game species. Forests eliminate shade-intolerant plants and are inimical to many insects, reptiles, mammals, and birds that seek open habitats for nesting and food. Across the eastern United States, open lands and their species are the most rapidly declining habitats.

To understand this decline, we need to visit with Henry Thoreau and witness the processes that produced and then erased his mid-nineteenth-century landscape.

Toward the end of Thoreau’s life in 1862, New England was nearing its nadir in forest cover and agrarian splendor. Outside of the far north and mountains, half of the region was clear of trees and heavily grazed by livestock. Remaining forests were cut heavily for fuel and lumber. As forestry expanded northward, timber production peaked around 1910, frequently accompanied by fire, another disturbance greatly increased by colonization. Employed to clear forest, or keep areas open, fire escaped through carelessness and was spread widely by locomotives. These novel forces wrought by colonial hands––deforestation, fire, and agriculture––generated a century-long period around Thoreau’s life when nature in New England was furthest from its longstanding forested condition.

Forest cover (black) and open farmland (white) in Massachusetts in 1830 and 1999. In the nineteenth century, the landscape was open and most forests were heavily cut woodlots. Image courtesy of Brian Hall and Harvard Forest

With his remarkable historical insight, Thoreau was keenly aware of this transformation and yet intriguingly ambivalent concerning its consequences. Thoreau’s despair at the great losses of ancient woods, noble animals, and native inhabitants is well known. Less appreciated is his embrace of the beauty and delightful diversity of the resulting agrarian landscape of lowland meadows, upland pastures, hayfields, and sprout woodlands. Butterflies and insects; tantalizing birds and song; and the botanical splendor of open farmland, thickets, and flooded meadows captivated Thoreau and filled his journal. The countryside formed an ever-changing mosaic in which each species’ distinct habitat was shaped by human hands and nature. Raw nature, which Thoreau sought on three trips to northern Maine, was unrivaled in wildness. But the open cultural countryside of Concord was engaging and livable.

Thoreau’s contemporary, ornithologist William Peabody, also recognized the region’s wildlife as a distinct product of cultural and natural processes. In his Report on the Birds of Massachusetts (1840), many species were characterized in relationship to anthropogenic landscapes and structures.

The [Bobwhite] quail is a gentle bird… resort[ing] to open fields in search of food, such as grain, buck wheat and Indian corn

The barn-yard affords [the Whippoorwill] a foraging ground, which it often visits; sometimes it takes its station on the step of the house door.

The Killdeer plover is found in open fields [and] in the presence of horses, cows and sheep... [They] follow the ploughman, to seize [worms] which he has turned out from the ground.

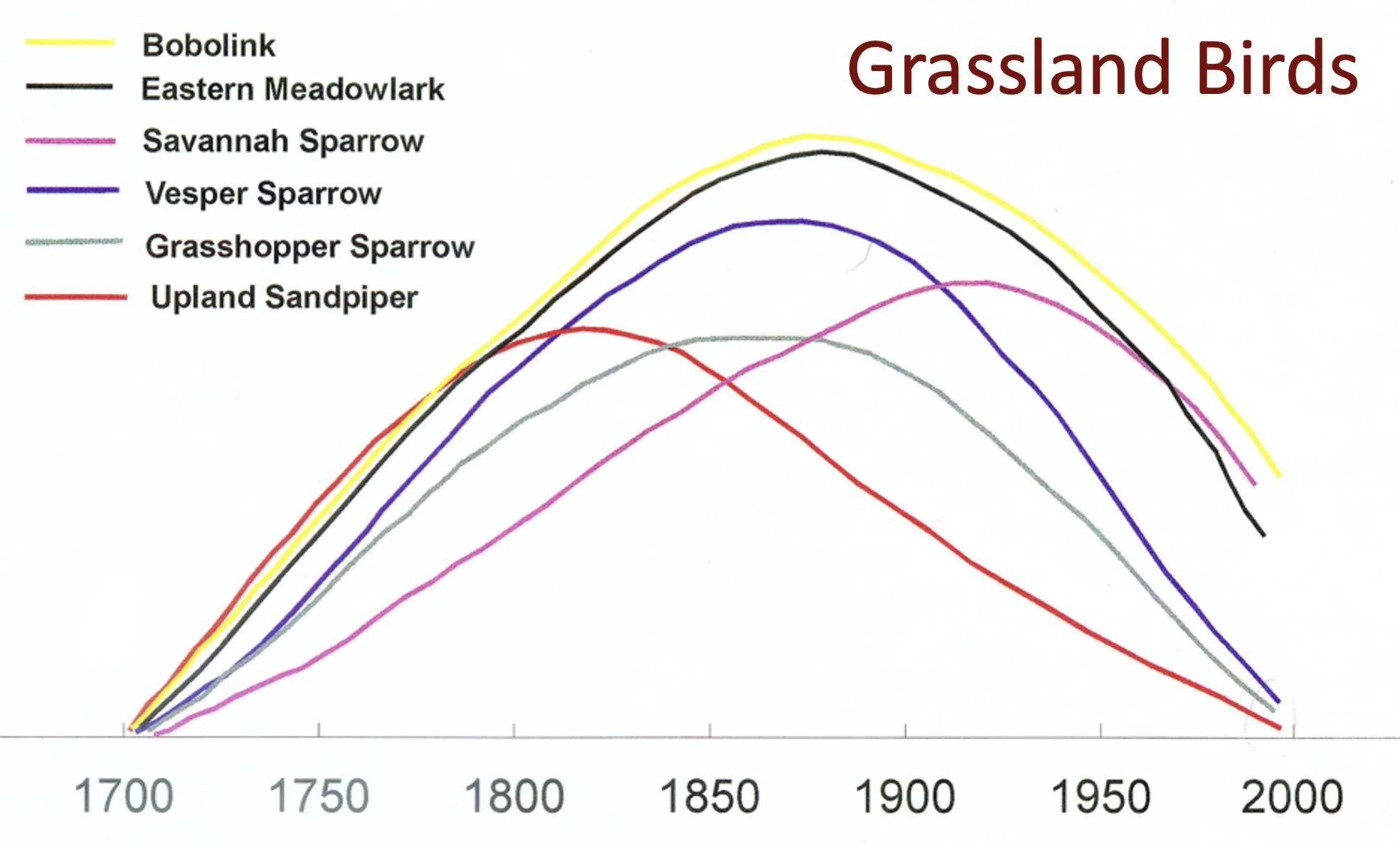

The generalized trend of select grassland bird species in southern New England. Image Courtesy of Harvard Forest, adapted from “Wildlife Dynamics in the Changing New England Landscape”

The disappearance of that open landscape was driven by forest succession, a process that Thoreau described, defined, and marveled at in his last years. As grain and livestock production moved west with U.S. expansion, and New England farmers shifted to more intensive dairy and vegetable production, abandoned fields and pastures filled with trees. As farm and timber production decreased, so did the ravages of fire. Openland habitats and species commenced a precipitous decline to the present.

Herein lies a great challenge for New England conservation. To slow climate change, we need to store carbon in forests and soils. Given the region’s forest history, that goal should be surprisingly easy to achieve. Simply let forests spread naturally and replenish carbon stocks depleted by colonial activity. That process yields a concomitant biodiversity bonanza, bringing back moose, bear, deer, fisher, beaver, pileated woodpeckers, and other forest animal and plant species that Thoreau only mused on. Yet, the losses of species from his agrarian landscape mounted. A century and a half after Thoreau first documented the successional march of trees across New England fields, anthropogenic openlands and sprout forests continue to decline.

Unfortunately, New England conservation has never fully recognized or embraced the historical roots of this dilemma. Some voices erroneously characterize upland grasslands, shrublands, and barrens as “natural.” Despite their colonial origins, others portray them as remnants of Indigenous land management, an interpretation challenged by Indigenous sources, archaeology, and paleoecology. Many simply yearn to retain familiar and increasingly uncommon species of plants and wildlife. Others, including myself, grew up with and love the New England blend of forest and farm.

Thus, with mixed rationale, public agencies and private organizations expend enormous resources and fuel climate change in an endless effort to combat succession and freeze landscape conditions and biodiversity. Former pastures, hayfields, and cutover woodlots are intensively managed as open natural areas, often with little reference to the agricultural and wood production systems that created them—and could effectively recreate them today.

“Butterflies and insects; tantalizing birds and song; and the botanical splendor of open farmland, thickets, and flooded meadows captivated Thoreau and filled his journal. ”

So, when the governor of Massachusetts issues two major directives, as Maura Healey did in recent years, one prioritizing climate mitigation and another biodiversity, how do we advance both ecologically and effectively?

We might begin by adopting the British, European, and Thoreauvian approach of embracing both natural and cultural landscapes and applying the landscape’s history in guiding the management of each in ways that also employ ongoing food and wood production.

From history we learn:

The pre-colonial landscape was predominantly old forest shaped by natural processes with local impacts by Indigenous people who lived lightly on the land. These are now our most poorly represented land cover;

Openlands proliferated with colonial forest clearance, fire, and agriculture;

Novel plant and wildlife assemblages developed opportunistically in grasslands, shrublands, and sprout woodlands; peaked through Thoreau’s life; and declined alongside agriculture, intensive logging, and escaped fires; and

Openland conservation areas have all been shaped by intensive colonial land use.

Applying this history, we should begin by abandoning current ahistorical practices that are disconnected from food and wood production, such as clearcutting and chipping, prescribed fire, brushhogging, and herbicide applications that support this intensive work. We can then fashion an integrated approach to conservation management that supports natural and cultural practices in complementary fashion across the landscape. The result will be more forest and greatly reduced goals for openlands, but a much greater promise of success in supporting them. Some suggested considerations and actions:

Across most of the landscape, in continuously forested and newly reforested areas, natural processes and native biodiversity can be supported in Wildlands where active management is excluded and Woodlands where maturing forests are managed carefully and much less intensively for wood products and select wildlife habitats. Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities argues that forest could cover at least 70 percent of New England, with Wildlands covering at least 10 percent and managed Woodlands the rest. Management of Wildlands and active management of Woodlands would benefit from Indigenous knowledge and ecological science;

Over time, natural growth and disturbances (wind, ice, insects, beaver, disease) will diversify all forests, adding complexity and additional habitats;

Once existing grasslands, shrublands, and young forests are assessed ecologically, their management can be informed by their land use history. Applying that history would integrate conservation and agricultural practices ecologically, especially grazing and hay production; and

Conservationists could also look to existing modern land use and artificial habitats—transmission lines, solar arrays, airfields, military training areas, landfills, and our own backyards—to play a major role in maintaining grassland and shrubland species. These should be quantified and included in conservation planning.

Conservation grazing at the Harvard Forest. The cattle are owned by a farmer with the pasture leased at no cost. The site is the former Petersham Golf Course, which was established on pastures that had been grazed for more than a century. Photo © David Foster

This approach of interpreting and applying cultural and natural processes in conservation management is already being advanced by select groups such as the Applied Farmscape Ecology Research Collaborative and Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank, and more broadly in hayfield management for bobolinks.

There are great advantages to this approach. Applying the processes that created the desired habitats historically creates a much stronger foundation for success than ahistorical methods. Of equal importance, it integrates much-needed agricultural and wood production in conservation management, rather than simply deploying monetary and personnel resources solely for management. This reduces costs, increases long-term viability, maximizes human benefits, reduces environmental damage, and increases the extent of forest cover in the region.

Integrated and historically-informed management of cultural and natural lands offers an alternative that can yield climate and biodiversity benefits along with food, resources, and community support.

David Foster is an ecologist, Director Emeritus of the Harvard Forest, and President Emeritus of the Highstead Foundation. He co-founded the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities initiative in 2010; was lead writer of Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future in 2023; and served as a member of the Massachusetts Climate Forestry Committee. David has written and edited books including Thoreau’s Country: Journey Through a Transformed Landscape and A Meeting of Land and Sea: The Nature and Future of Martha’s Vineyard.