Modeling Future Scenarios of Massachusetts Forests

A Tale of Resilience

Editor’s Note: I saw Meg MacLean present a summary of the Massachusetts Forest Carbon Study at the Canopy Forestry Forum this spring. It was the last session of the day, but I noticed members of the audience leaning forward with intense interest as Meg unpacked the complicated figures that compared the long-term carbon impact of scenarios that increased local wood harvesting to scenarios that maintained current levels of harvesting, but established more wild reserves. There is an ongoing debate in the forest conservation community about which would be better for the climate. The surprising and gratifying result? There isn’t much difference. Another striking result: Large disturbances such as hurricanes will likely have a much bigger impact than any differences in rates of harvesting. My conclusion? Let’s protect all the forest we can, establish lots of wild reserves, harvest the rest in responsible ways, and stop arguing about this. See if you agree. – Brian Donahue.

As we face the stresses of climate change, land use choices will have an important impact on carbon emissions, sequestration, and storage. In Massachusetts, many of these questions revolve around our forests. Forests cover about 56 percent of Massachusetts and provide our largest land-based carbon sink, removing around 11 percent of our greenhouse gas emissions annually. This has led to important questions about how best to protect and steward these lands into the future.

A group of researchers from UMass Amherst and Harvard Forest (Harvard University), alongside representatives from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, worked with stakeholders to design and model scenarios of future land use to better understand the emission consequences of different land-use actions (Forest Carbon Study, 2025). In conversations with stakeholders, a central question emerged: Would maximizing passively-managed reserves, maximizing local wood production, or a combination of the two give the best climate result, compared to how we manage our forests today?

Future Scenarios

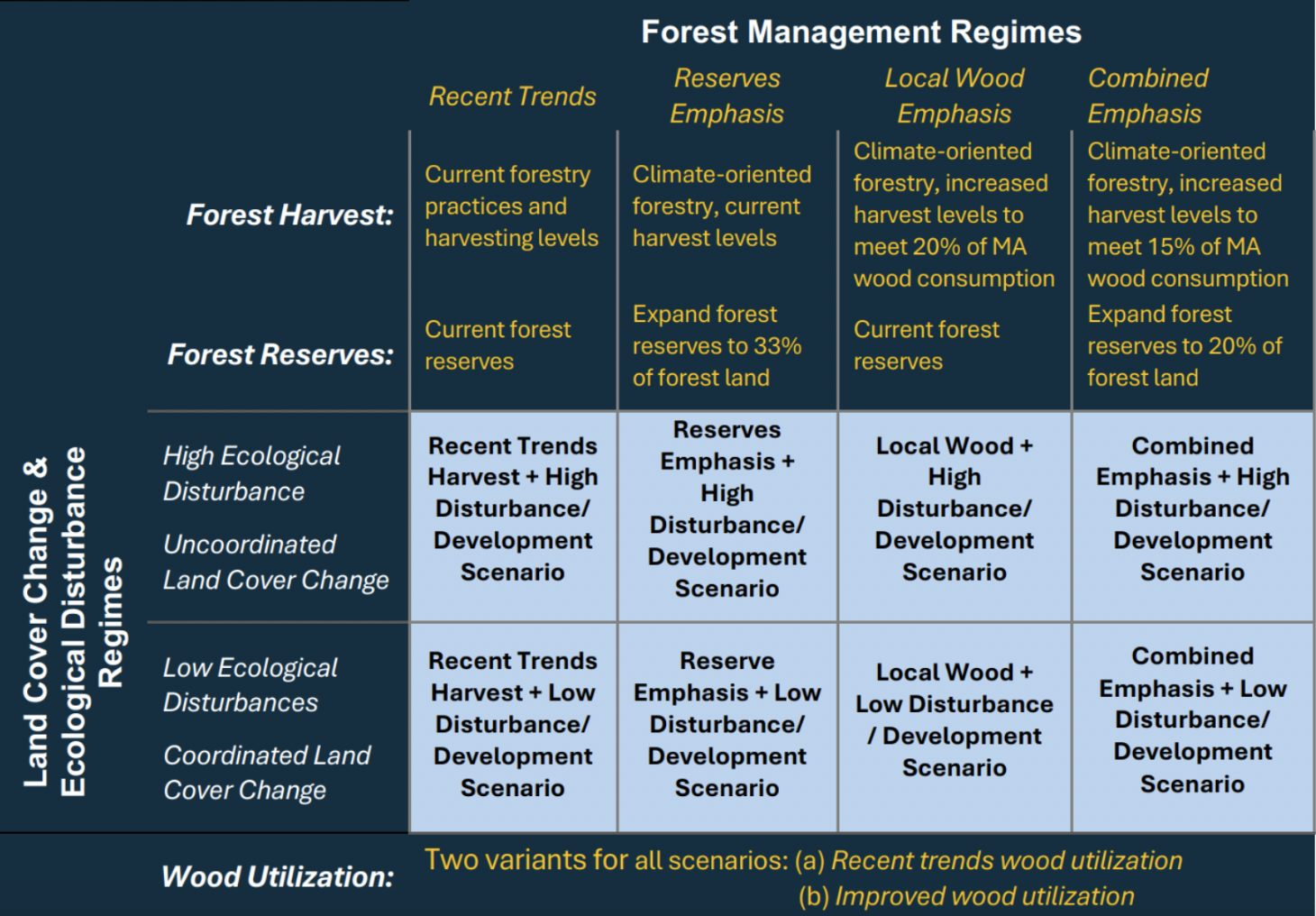

To try to answer these questions, we created three alternative future scenarios of forest management. The first (Reserves Emphasis) seeks to expand passively-managed forest reserves from the current level of less than 4 percent of forest land to 33 percent of forest land. The second (Local Wood Emphasis) tries to meet more of our current wood product consumption in Massachusetts, increasing from less than 7 percent of total consumption in the state to 20 percent. The third (Combined Emphasis) tries to balance these two approaches by raising timber production to 15 percent of current total consumption and expanding forest reserves to 20 percent of the forest area (Figure 1). These scenarios were designed to push the envelope of timber production or reserves beyond other suggested pathways for meeting our conservation goals, such as those outlined in Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities or Beyond the “Illusion of Preservation.” For comparison, we also simulated a continuation of Recent Trends in land use. Since we were looking at the long-term impacts of forest management decisions on forests and carbon, we ran the scenarios from 2020 to 2100 to allow us to look at a time scale closer to that of forest change.

In each one of these scenarios (except for the continuation of Recent Trends) we shifted to more climate-oriented forest management practices. We chose to keep timber production at current levels (or higher) to ensure that we were not creating a scenario that would result in existing timber production being shifted out of state where we are not tracking emissions. So, the Reserves Emphasis scenario still harvested as much timber as Recent Trends, while the Local Wood and Combined Emphasis scenarios harvested more. Finally, we ran each of the four scenarios under two disturbance regimes: a Low Disturbance regime that included small gap-scale disturbances such as wind, ice, insects and diseases; and a High Disturbance regime that also included hurricanes similar to those that occurred in the twentieth century, but with a slight increase in intensity as is predicted with climate change.

Future scenarios of land use, focusing on forest processes (Table E1 in the Forest Carbon Study). Courtesy of Forest Carbon Study, 2025

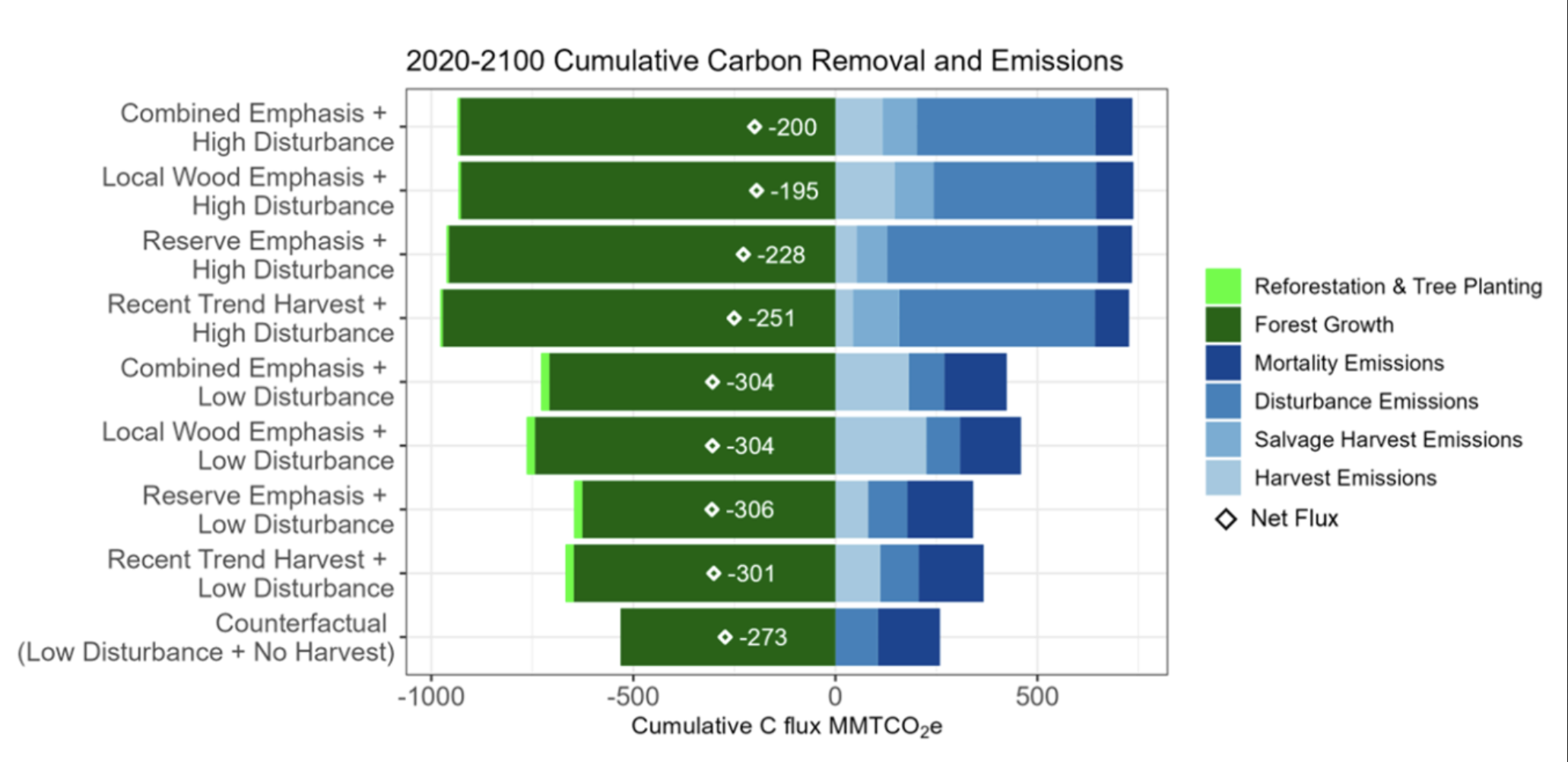

We then tracked carbon emissions, sequestration, and storage, both in the forests and in the wood harvested for timber. The overwhelming result across all scenarios is that our forests will continue to be a net carbon sink through 2100, even with large-scale disturbances like hurricanes, so long as they are able to grow back following the disturbance. Total predicted net carbon sequestration ranges from 195 MMTCO2e to 306 MMTCO2e, and the largest determinant of the difference in net sequestration is the presence of hurricanes (as shown by the “net flux” diamonds in Figure 2).

Carbon Impact

Among the four different forest use scenarios, there is little difference in net carbon sequestration by 2100, especially under the Low Disturbance regime. Despite trying to push the envelope on both timber production and wild reserves, if there are no major disturbances, these differences in land use do not change the overall carbon picture very much in 2100. However, under the High Disturbance regime, we do see small differences in net carbon sequestration by land use scenario. When hurricanes are at play (which, unfortunately, will be more likely than not), the higher timber production scenarios do not see quite the same amount of forest recovery and sequestration as those with current levels of harvesting (Figure 2).

Cumulative carbon emissions (blue) and removal (green) in each of the modeled scenarios by 2100. The diamond represents the net carbon emissions for that scenario where negative values represent net carbon sequestration (Figure 17 in the Forest Carbon Study). Courtesy of Forest Carbon Study, 2025

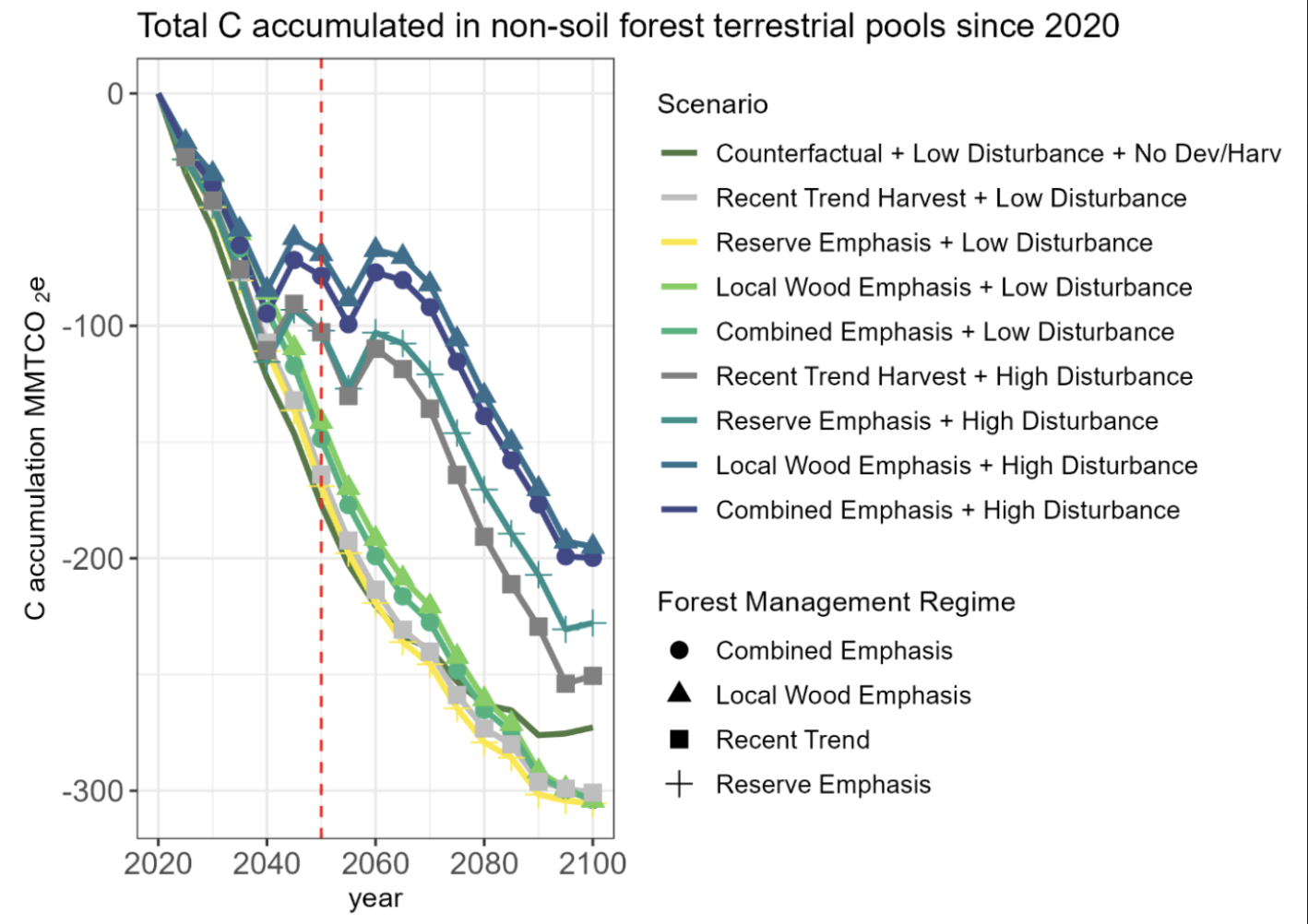

Looking more closely at how these scenarios play out decade by decade, we can track how the different land use decisions and disturbances impact carbon stored in all pools combined: live aboveground wood and belowground roots, dead and downed wood, harvested wood products, and landfills (Figure 3). Again, the four High Disturbance and the four Low Disturbance regimes cluster together, with the Low Disturbance group storing the most carbon overall. You can see in Figure 3 how hurricanes impact stored carbon: The High Disturbance lines jump upward, especially during the larger hurricanes (2038, 2054, and 2091), due to the loss of carbon stored in live trees. However, some of these emissions are offset by the enhanced sequestration that follows the intense disturbances. The shape of the High Disturbance curve will change dramatically depending on the real timing and strength of hurricanes to come!

You can also see how the rate at which carbon is moved into the stored pools remains faster for the High Disturbance scenarios than the Low Disturbance scenarios later in the century. The slowing of carbon removal under the Low Disturbance regime is likely due to the aging of the forest, since on average younger forests are able to sequester carbon at a slightly faster rate than older forests (though there is a lot of variation). The differences among the Low Disturbance scenarios are more pronounced in 2050 (the year Massachusetts has agreed to be net zero), since the increased sequestration that follows the higher rate of harvesting in the Local Wood and Combined scenarios is most beneficial later in the century.

Total stored carbon from 2020 to 2100 in all non-soil carbon pools (including in-forest live and dead wood and harvest residues, new forest and tree live wood, and out-of-forest wood products in use and in landfills). Note that the “High Disturbance” scenarios include major hurricanes. The red dashed line indicates 2050, Massachusetts’ net zero compliance year (Figure E2 in the Forest Carbon Study). Courtesy of Forest Carbon Study, 2025

Wood Products Implications

Finally, each of these scenarios produces a different quantity of wood products as well, potentially alleviating the demand for out-of-state wood and thereby the emissions that come with that production. We used a production approach to carbon accounting (as was used by the IPCC), so we did not account for the emissions from wood produced elsewhere but consumed in Massachusetts. For example, the Local Wood + High Disturbance scenario produced nearly twice as many wood products as the Recent Trends + High Disturbance scenario, or equivalent to 107 MMTCO2e in wood products that would have to be sourced outside of the state. With our current approach, we do not account for those out-of-state emissions in the Recent Trends scenario. While our production emissions numbers are not directly comparable to what might be emitted elsewhere to produce these timber products, beginning to account for the emissions of producing the same amount of wood products in each scenario would lessen the difference in net carbon emissions between the scenarios.

The major takeaway from this study is that our forests are quite resilient. Some amount of disturbance, whether caused by humans or nature, will allow our forests to remain diverse in species, structure, and age class distribution, helping to secure rates of sequestration further into the future. The biggest factor determining future net carbon sequestration will be the number and intensity of hurricanes the forests of Massachusetts experience this century. Given that warming is likely to increase the intensity of these disturbances, doing our best to mitigate climate change by reducing all emissions may also be our best bet for protecting our forests.

Meg Graham MacLean is a Senior Lecturer and Research Scholar of carbon accounting at the University of Massachusetts - Amherst. She is passionate about collaborating with forestry, environmental, and community leaders at all levels to better understand the human-environment interactions that impact our forest ecosystems. Her research uses innovative quantitative methods to explore how the forested landscape is changing due to human and climate pressures, the impacts of these changes on forest ecosystems and carbon dynamics, and how to monitor and model these changes with the goal of informing policy and management decisions. Learn more