Trees, Mothering, and Reciprocity

An Interview with Leslie Jonas, Indigenous Elder

Editor’s Note: At the recent Northeastern Old Growth Conference, Leslie Jonas offered a compelling and heartfelt reflection on Indigenous relationships to the land and to old-growth forests. She began with a global view and brought us right home to New England, and to her own neighborhood of Cape Cod, where she spent her childhood wandering about the woods, the glacial ponds, and the dunes. Having spent many childhood days on Cape Cod myself, and having enjoyed a free-ranging and untethered childhood, I could relate to her plea that we allow children to do the same. We had a wonderful and long conversation a few weeks after the conference, and explored some of her ideas in greater depth. The interview is edited for brevity and clarity. – Liz Thompson

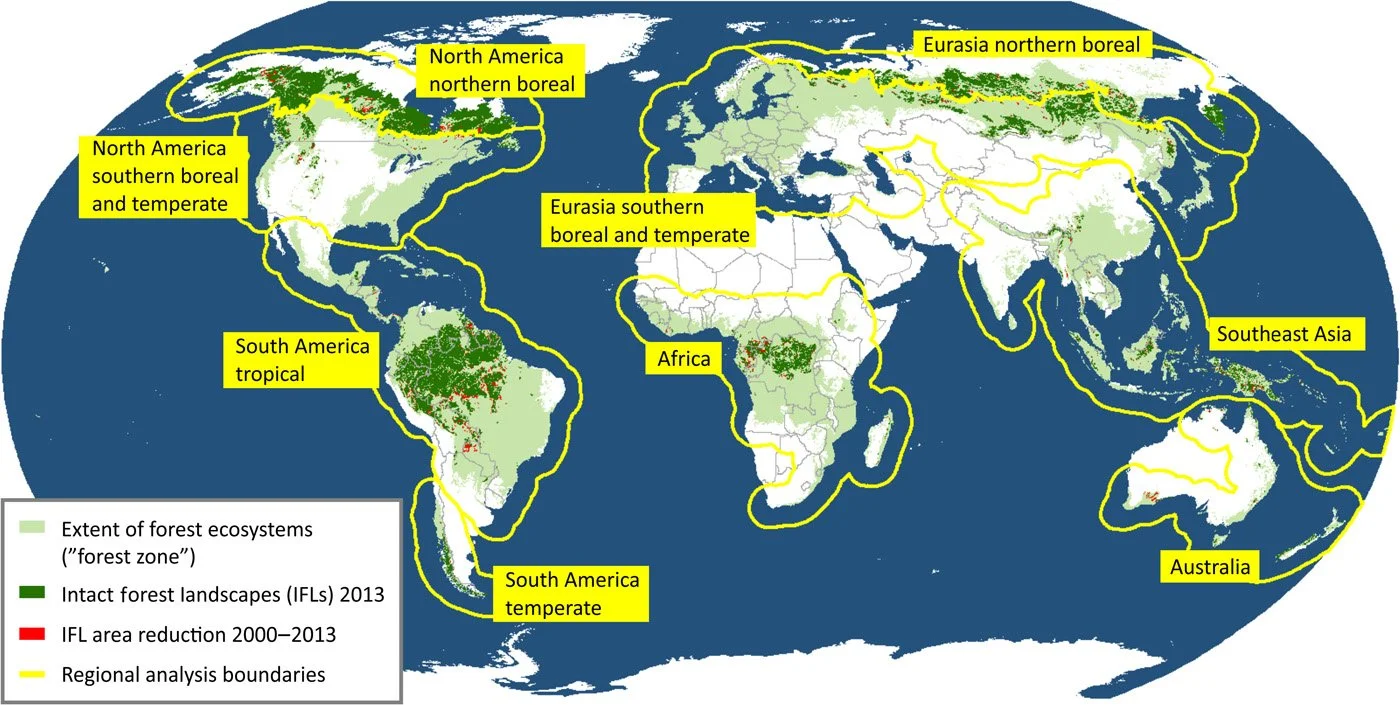

Liz Thompson: Thank you, Leslie, for taking the time to talk with us. I want to start with some terminology, some definitions. In your presentation at the conference, you talked about “intact forest landscapes” and the work that’s happening to inventory those lands. How do you distinguish between “old-growth forest” and “Intact Forest Landscapes” [IFLs]?

Leslie Jonas: Let’s talk about “Wildlands” too, as that’s a commonly used term in this discussion as well. All of these types of landscapes share important details, primarily that there has been little to no human disturbance. IFLs are vast, they are massive. Within IFLs, you can find old growth, you can find forests where there’s a lot of debris in the woods, lots of growth in multiple canopy layers, with a substantial amount of aboveground biomass, and with multigenerational stands of trees in the woods. Intact Forest Landscapes are probably more protected than many old-growth forests because they’re so remote and because it’s hard to get into them: They’re boundless, unfragmented, and remote.

Intact Forest Landscapes (IFLs) worldwide. Note that New England is not within an IFL. Image courtesy of the IFL Mapping Team

As for Wildlands—there’s a lot of energy around “rewilding” right now, which is a more intentional kind of longer-term strategy for healing and repair. When Northeast Wilderness Trust (NEWT) embarked on their strategy of supporting rewilding, our perspective at the Native Land Conservancy (NLC) as an Indigenous group was to suggest a phased approach. You don’t have to remove the human from the environment, but we understand that there has to be minimal impact. Within an Indigenous worldview, you would never take the human out of the natural world. For us, there is a relationship, a kinship, that we have honed for millennia. So it feels punishing to Indigenous people to restrict access to these rewilded areas because of all the damage that’s been done. We understand that these negatively impacted areas need time to repair— but it doesn’t make sense for us to remove the human relationship to do that. We believe that part of the reparative work will come from human interaction. So if we see something in the woods, like a clogged waterway from invasive species where herring can’t run through, we can clean that out. If we see invasives overwhelming a specific native plant that is needed to maintain the ecological balance of an area, we can pull the invasives back to allow the native species to grow naturally. So, we think human impact and human relationality is key in the process of rewilding.

LT: How did NEWT respond to that?

LJ: When NEWT first started out, their belief in rewilding as just “leave it alone” was rooted in understanding that the devastation in these spaces was caused because we (humans) were in the woods and doing damage. This was a different view, a view that was more modern, less informed by and less inclusive of Indigenous worldviews borne from our relationship within these spaces that goes back millennia. We then started to understand one another better and an MOU and cultural respect easement were discussed. NEWT pulled back from the “absolute” no human interference, no disturbance—because human connection and relationality doesn’t always mean that humans are disturbing it. Some of the Western words that are used in these kinds of conversations, Liz, can be negative. We would say human kin, human relationality, and human connectedness, as opposed to human disturbance. So, before we start doing all this work together, sometimes it’s good to come together and define what these words mean to one another, and then we can speak a more common language.

Editor’s Note: In 2021 NLC and NEWT formally entered into a partnership that honors human presence at Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve in Kingston, Massachusetts.

Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve, Kingston, Massachusetts. Photo © Liz Thompson

Representatives of Native Land Conservancy (Ramona Peters, NLC Founder and President and Leslie Jonas, NLC Founding Board Officer) and Northeast Wilderness Trust (Mark Anderson, NEWT Board Emeritus and Jon Leibowitz, NEWT President and CEO) on a walk to celebrate our collaboration on the shared stewardship of Muddy Pond in Kingston, Massachusetts, now the Wampanoag Commonlands. Photo Courtesy Northeast Wilderness Trust

LT: That makes a lot of sense to me. It rings true to me too. I grew up in Massachusetts, so I know what real disturbance looks like, and how it can completely change the land. And it’s easy for me to call it negative, to call it disturbance, to call it impact, when I just haven’t experienced the kinship, the type of connection, or the relationality that you’re talking about.

LJ: Yes. A distinct element of relationality is to be in the woods, to be in connection to and with. I spend much of my time, at least three days a week, maybe four, in the woods. This is where I re-center, where I can clear a lot of the chaos that everyday life and work can create. Sometimes you don’t feel like you can get out of your own way, you know? Problem solving gets better for me when I go into the woods and re-center. But our worldview of the natural world as kin is powerful, because the way that we interact and relate is the way that we would treat a family member whom we honor, respect and adore. It’s that same kind of connectedness and relationality. It’s an interconnectivity where we truly feel connected. We’re part of these woods, and so therefore they’re a part of us as well, and they’re sacred. So, we honor that in a way where we don’t over-forage, we don’t over-take, but we try to live in balance and tend to her with care, to protect her. That’s innate. It is inherent in our DNA.

So, all of these more modern concepts [rewilding, wilderness]—we talk about them and we’ll work within them, but we will bump up against them when folks say there can be no human interaction here, because we have never lived that way. We’ve never had to remove ourselves from these spaces because of the damage that’s been done through colonization and corporate extraction. We’ll get to this when we talk about gift economies, but if we think nature is there for the taking, if we only look at nature as a commodity or as a resource to be extracted, that’s lethal for the future of the world and mankind.

LT: Let’s go to that. Could you tell us more about what you mean by “gift economy”?

LJ: Have you read both Braiding Sweetgrass and The Serviceberry? You’ve got to read Serviceberry. Robin Wall Kimmerer is so poetic in the way she describes relationships. She describes a gift economy so beautifully in this book, Liz, that it will change the way you look at the natural world. Throughout life, depending on the voices that come into play and impress us or change our views and our relationships, relationship to the natural world is always moving. It’s not linear. It is definitely a moving, fluid thing. I think there’s so much room for growth for all of us. I’m still growing around my relationship with the natural world based on what I find….each and every day.

But basically, a gift economy means that we don’t just take and keep for ourselves, but that we pay it forward. It is about collective care. So, we share the resources of the natural world and we give it through this community-oriented mindset. Say I go and pick a ton of blueberries, I’m going to make muffins and pies and I’m going to give some of those pies to my neighbors. I was gifted and so I’m going to pay it forward. That’s a gift economy, as opposed to an extractive economy that takes for the benefit of a small group or an individual. That economy can come from greedy, power-hungry mindsets. The gift economy is a balanced, reciprocal, pay-it-forward model. You get something, you give part of it away, you share. The natural world’s future and its ability to thrive depends on that. We’ve seen and witnessed when it’s not part of that gift economy. We’ve seen the pine barren woodlands, these over-foraged spaces.

“I was gifted and so I’m going to pay it forward.” Photo © Leslie Jonas

In southeastern Massachusetts, we’re suffering from extreme strip mining or sand mining. They’re deforesting the pine barren woodlands for the sand and gravel and the silica in the sand. It’s greed from a few groups. The money that they’re getting is coming from strip mining these pristine, unique natural settings. There’s only three of this type of pine barren woodlands left in the world, and southeastern Massachusetts has two of them. So, why would this state, where we call ourselves blue, why would we allow this? With strong environmental groups, with the environmental protection agencies at the state and federal level, with federal law protecting safe drinking water and clean air…all of these essential resources are being greatly impacted. It’s happening! We’re in that fight right now as the Community Land and Water Coalition of southeastern Massachusetts. We’re fighting it hard.

Sand mining begins with the leveling of native pine ecosystems, which have been reduced to narrow strips, as seen in this image taken in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of Community Land and Water Coalition

Strip mining, sand mining, land mining…. is the complete opposite of a gift economy. It is extractive. It is assaulting. We believe there’s corruption, because people are paying others to turn their heads and allow this obscene level of non-stop strip mining in this area. Think about the mindset that does not care about the future of those pristine ecosystems and the impacts to the waterways and the aquifer that’s underneath feeding water to 200,000+ people. It’s all threatened! They have found the loopholes in the system to get around environmental impact studies and statements. Nothing’s been done. It feels like every two weeks, there’s another permit being allowed for another four or five acres of strip mining. They’re doing this under the guise of cranberry agriculture, Liz, and there’s not a cranberry to be found. There hasn’t been for decades.

Commercial cranberry bog at harvest time. Photo © Leslie Jonas

LT: That is so hard to see, but thank you for telling me about it.

I was hoping to ask about reciprocity, too. I think you’ve already addressed it in the “giving back” of a gift economy, is that what you mean?

LJ: Yes—and it means being in balance. A reciprocal relationship has a lot to do with the gift economy. The gift economy is more rooted in the idea of passing along the gifts that you received, whereas “reciprocity” refers to the balance of give and take. But these terms are all blended; it’s all about gratitude and the ways that we’re grateful. We live in this “take, take, take” society and in an economy where extraction might seem like the best way to stay fluid and sound. And that’s not the way an Indigenous person might think. Folks associated with this extractive economy mindset often think that more is better and less means you don’t have enough. This fear of not having enough—that seems to be the underlying theme for many. Instead, what if we take just what we need in a particular time, leave enough for others, leave enough for the system to maintain itself, and to not “shock” that system? Extractive, patriarchal Western systems are based on taking so much that you shock those natural systems, in many cases to the degree that they can’t recover for a very, very long time…. If at all. That mindset goes against this whole idea of reciprocal balance of giving and taking. We’re not saying “you can’t have.” We’re saying “just take what you need and don’t take any more.” Greed does not exist in these worldviews.

LT: Could you share more on how the concept of motherhood connects to this worldview? You talk about a patriarchal society, a patriarchal system… What about a matriarchal point of view? How does that come into your worldview?

LJ: There’s a perfectly good reason why we often call the natural world “Mother Nature,” or why we call the Earth “Mother Earth.” We have all these references to the female. She is the giver of all life, and we wouldn’t have anything in this world without her. She is the queen caretaker. I come from a matrilineal and matriarchal system. Our Indigenous Mashpee Wampanoag cultural way of leadership stems from our clan mothers. Clans come from the natural world. I’m a member of the Eel clan, which is partially why I’m really connected to water as well. And these clan mothers lead the families in times of difficulty, in times of positivity, times of celebration and joy, and in teaching and guiding. So, when folks need some guidance, they might go to their clan mother. Mother Nature is sort of the indicator of the health of the relationship between humans and the earth. She is the one who connects us to all of our relations; the natural world relations and our human relations. It is the mother in all of these settings, whether it’s the mother sugar maple tree, who is giving and giving and taking all kinds of hits, this mother is the strength, the backbone, the family unit, and the one who holds it all together. The mother tree is the one who will send her strength and nutrients through her root system to the young, especially the ailing young. The teaching of trees is a great example of finding motherhood in nature, because the mother will send energy, through these root systems and offshoots of new growth, and she’ll send more vitamins to the weaker ones who need that extra boost to grow. Such a critically important testament to the power of nature and the resiliency of nature as the mother of all, the healer, the provider, and endless giver.

Sugar Maple, Mother Tree. Photo © Liz Thompson

[Women] don’t typically settle for mediocrity. We will bring it to the next level. I find that a lot with my female peers. I find that in nature as well. Mother Nature will do that. She won’t settle. If she’s fighting for her life, for her wellness, she will take things to the next level. So an example might be in the woods, after a cultural burn, you’ll see new growth. It may open up spaces for species that we haven’t seen for decades. Species may flourish after a small, managed cultural burn. I’m not talking about tons of acres that sometimes the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) might do. I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about an Indigenous management practice that we’ve engaged in for thousands of years to work with Mother Earth to reinvigorate the soil and to invite those new species back. And that is rooted in a female perspective.

LT: I’m interested in why DCR feels that they need to do these big burns, and, specifically, do they justify it based on Indigenous practices?

LJ: They’re doing [this burning] on thousands of acres. Sometimes it’s pretty scary. They’re coming up against a lot of opposition by some of the environmental conservation groups. They do use arguments like “This is an old Indigenous land management practice that’s been practiced for thousands of years.” No, please don’t take advantage of us like that. We didn’t burn thousands and thousands of acres of pristine Wildlands. No, we did not. We would burn the farm in the back to invigorate new growth for that next spring. It would be an acre or two.

This is an example, Liz, of a patriarchal system in action. These folks want to go out there and burn, burn, burn, because they think they’re getting rid of the fuel that could be subject to a wildfire, due to the impacts of climate and some of the drought that we’re experiencing. Yes, there is an increased risk for wildfire when we have had months without rain, but how about we just act as better stewards and watch the woods? What if we have caretakers, have forest rangers, have more folks out in the woods? What about we bring our children out there, so that they learn to build a relationship, to watch for things that might happen?

“If we think nature is there for the taking, if we only look at nature as a commodity or as a resource to be extracted, that’s lethal for the future of the world and mankind.”

LT: At the recent Old Growth Forest conference, some participants came to the event wanting to learn about how they can protect old-growth forests, Wildlands, and intact forests, asking “What can I do? What are the tools out there? How can I move forward?” What would you tell someone asking these questions? How can they make the world better in terms of promoting the values that old forests, in any of their forms, can offer? Do you think we are on the right path in talking about protection tools?

LJ: Well, at least Indigenous voices are being invited to the conversation, so that these alternatives to the rigid Western views are heard.

For centuries, Western science has taught us that everything is measured with the tools that we’ve developed, or technologies. We would use these tools to measure the conditions of the forests, or this new invasive species, or a threat to a specific species. We would use technology and tools to learn.

In an Indigenous approach and worldview, we would say first, make sure you have a relationship to this space. Put the tools down for a moment and use your human sensory system. Use these natural tools that we were gifted with. Use the tools of sight, smell, sound, and the way something makes you feel. In a Western science approach, Nature is still looked at as something to be extracted from, or even as something to learn from. It is still viewed as a commodity and in many cases researched from that perspective. The human relationship doesn’t’ seem to carry much value.

People exploring Muddy Pond WIlderness Preserve. Photo © Liz Thompson

The Indigenous worldview might honor and respect the foundational relationship, a different experience than taking from it. So, building that balance between the honoring of something before we take from it and measure it is key. A lot of [researchers] I work with, especially on projects in waterways, may have never really had a relationship with the water. At least not a spiritual one. And they can actually be kind of dumbfounded by that notion, and think something like “Oh, no, I’m not doing that. That’s too ethereal.” But the folks who do accept this different relationship come back with “Oh, my goodness. I never knew. I have this whole different dynamic going on with this kind of work. Now I have a relationship here, and I feel differently. I feel better.”

So, what are we to do? We need to bridge relationships with Indigenous people so we can go out into the woods and learn from each other. I think the technology and tools and the Indigenous wisdom can bring about much more robust solutions to the work. I’m not dismissing anything here. I’m just saying there’s another way as well, and that’s a different way of knowing that’s more attached to the connection...to the relationship. I think that’s necessary for us to grow together and heal together, especially with the natural world at the forefront.

LT: How do you think about fostering that way of being in the next generation?

LJ: That’s really important. I speak a lot about the loss of connection with these generations behind us because of the onset of technology. A lot of younger folks are screen addicted, so they don’t go out in the woods. I spent 12 to 14 hours a day in the woods growing up on Cape Cod. We jumped the ditches of the cranberry bogs, we ran through the woods—we lived in the woods until dark. We went out first thing in the morning, and we came back in the dark, and we loved it. I never felt more confident and I never felt more safe. We were loaded up with wood ticks, we had dog ticks on us all of the time. Now I’m completely grossed out by them, but back then, we would just rip them out of our heads and keep going. We would eat the berries in the woods for lunch so we didn’t have to go home to eat. We would spend a lot of time at the ponds like Coonamessett, or at the New Alchemy [Institute] (now the Green Ctr) because they were engaged in organic farming.

We need to bring the next generations with us. If we just hang out as elders by ourselves and we do all this work and just talk and talk and talk together, we’re doing nothing. We’re going to die at some point, and if we haven’t taught them, educated them and brought them out into the woods, then they won’t have the connection. We have to teach them to build relationships. It’s the same for Indigenous people, Liz: Our kids are screen addicted, too. They’re not going outside as often. I would go fishing every day in the summertime when I was growing up on Cape Cod. I went shellfishing with my dad, we went crabbing, we went fishing, we planted our own gardens, we grew our own vegetables. These kids aren’t doing that. It’s on us. We gave them these phones, the iPads and the laptops. It has to be more like, let’s go in the woods. Let’s go for a walk. Let’s see how many trees we can name and how many kinds of birds we hear.

Photo © Kyle Gray

LT: In your talk at the conference, and again a few minutes ago, you talked about the “mother tree” giving food to the children. Maybe that’s what this is about? Like being a mother tree?

LJ: Robin Wall Kimmerer, in her book, writes of herself as the apple tree that produces this fruit, her young, and then she sends them off into the world. She says that in her book. And it just moves me to tears.

Photo © Liz Thompson

That’s what we do, and that’s what we’re supposed to do. If we’ve done our jobs well, we’ve raised our young to go off into the world with their sweetness and their kindness and their generosity, just as she shares in her book. There’s a beauty there that words don’t describe very well, but it resonates deeply with me, in my spirit and my soul and my being. That’s what makes us feel good as mothers, to know that we’ve done our job in raising our young to go out and to be good people. Just to be good people. If that “good” means different things for different people, that’s OK. But to be a good person is a big deal, especially in a divisive environment and country right now.

LT: It’s a beautiful image. You’re leaving me with a lot. Thank you so much for your time and your wisdom.

LJ: It’s been great getting to know you and to work with you. Thank you!

Leslie Jonas. Photo © Daniel J. Hentz, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

Leslie Jonas is a native Cape Codder and Elder Eel Clan member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. She is an experienced planning and development strategist with a demonstrated history of working in media, higher education, tribal governments, and nonprofits. As a founding board officer, Leslie has spent the past 13 years helping to build the first Native-led land conservation trust east of the Mississippi, the Native Land Conservancy (NLC). She works to build a stronger relationship with the Wampanoag Nation and other northern Turtle Island Tribes—a testament to her dedication to fostering meaningful connections and promoting equitable and just environmental conservation. Currently, Leslie is MIT’s Martin Luther King Visiting Scholar/Professor in Anthropology, and is teaching a class in Indigenous studies, called Reimagining Indigeneity. She holds a BA in mass communications & television production from Emerson College, an MS in community economic development, and a certificate in DEI from Cornell University.