New England Policy Chronicle

Updates from Around the Region

Editor’s Note: To support this issue’s focus on old-growth forests, this edition of the New England Policy Chronicle explores how state policy from around the region intersects with the protection and management of our oldest forests. Forest policy discourse in New England varies widely—from active attempts to legislate old growth identification and protection in Maine, to new programs to incentivize protection of maturing woodlands in Vermont and Massachusetts, to a fairly quiet policy landscape in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

Accelerating the rate of protection for Wildlands and passively managed forests in New England is a key goal of the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities (WWF&C) initiative. As part of that effort, WWF&C researchers and collaborators have created two valuable resources for allies around the region.

First, our Dashboard offers a broad overview of how New England is progressing toward conservation targets laid out in the WWF&C vision, including a current snapshot of total conserved acres, conserved acres by type (Wildland, Woodland, and Farmland), and projections on how the current pace of land protection will or will not meet land protection goals in the future.

Specifically for Wildlands, the WWF&C partnership has developed a number of resources, reports, and tools that offer a deeper dive. These analyses are designed to articulate the importance of protecting wild and passively managed lands for human and natural communities alike, to quantify where and to what extent Wildlands have already been protected, and to offer useful definitions and guidance for conservation partners and policymakers. In addition to the full Wildlands in New England report, readers may be interested in the State Summaries developed as a complement to the regional analysis. Each summary offers a look at where and how Wildlands have been conserved to date and what’s needed to protect additional lands in the future. – Alex Redfield

Jump to page sections:

Maine

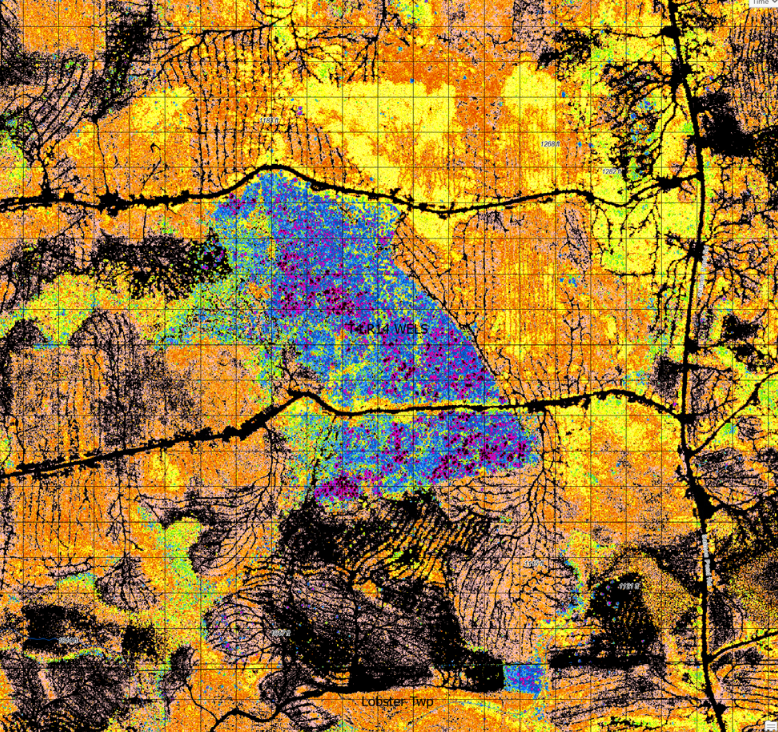

This image demonstrates a LiDAR analysis of canopy height in a forest. The blue-magenta “signature” often indicates a late-successional stand in the unorganized townships of Maine. Figure from Using LiDAR to Map, Quantify, and Conserve Late-successional Forest in Maine

In 2024, a team of researchers led by John Hagan at Our Climate Common published Using LiDAR to Map, Quantify, and Conserve Late-successional Forest in Maine, describing new methods and results that identify old forests across more than 10 million acres of unorganized territories in the Maine woods. Hagan describes the work and reflects on next steps elsewhere in this issue. By using LiDAR, a remote sensing technology using laser pulses beamed from an airborne sensor to identify landscape conditions on the ground, the study established that only three to four percent of this landscape is in a late-successional or old growth (LSOG) condition today, and that about two percent of those forests are being lost every year. Considering the globally significant values that these forests provide, State Senator Rick Bennett introduced LD 1529, “An Act to Enhance the Protection of High-value Natural Resources Statewide,” in the spring of 2025. This bill would have given preference to state-funded conservation projects that protect late-successional and old-growth forests, and would have required the Maine Forest Service to regularly report on the status of LSOG protection efforts and also to develop a comprehensive strategy to enhance the conservation of these unique parcels.

With initial opposition from timber industry groups and capacity concerns from state agency staff, a more modest version of the bill was eventually signed into law. The final language eliminated proposed changes to funding priorities and modified the reporting requirement to direct the Maine Forest Service, if and only if funding is made available, to compile a report on existing conservation strategies that could support enhanced protection of old growth. In a competitive budget cycle, the appropriations process failed to yield any funding for this reporting mandate, so advocates have turned to private and philanthropic sources in the hopes of quickly maintaining momentum toward state-level analysis and policy for LSOG conservation.

Putting aside the short-term objectives outlined in this bill, conservation advocates are optimistic that the legal recognition and definition of these valuable forests put forward in LD 1529 will set a strong foundation for future efforts to steward these places with care.

Learn more about the status of Wildland conservation in Maine in this State Summary from the Wildlands in New England report.

Rhode Island

This stand of 200- to 300-year-old beech trees in the Oakland Forest & Meadow is likely home to some of the oldest trees in Rhode Island. Over the last several years, beech leaf disease has killed nearly all of the older trees, and trails are closed for hikers’ safety. Photo courtesy of the Aquidneck Land Trust

The state with the fewest old trees in New England may very well be operating within the most acrimonious policy environment as it relates to old-growth forest. Over the past four sessions, legislators in the Ocean State have considered and ultimately rejected five different versions of a bill now known as the Old Growth Forest Protection Act. Behind these failed attempts to create new legislative mandates for publicly owned forest land is an increasingly unfortunate saga of false accusations and misrepresentations that have, at the very least, distracted stakeholders from advancing progressive policy. Beyond the substantive debate over if, where, and how human intervention is useful in supporting the growth of diverse forests, these bills pushed much farther than protecting old-growth forests, seeking to limit state agency ability to manage public lands across the state. Ellie Sennhenn provides an overview of the contentious discussions at the center of the most recent attempts at passing the Old Growth Forest Protection Act in her April 2025 piece “Forestry Bill Wants to Place ‘Handcuffs’ on DEM [Department of Environmental Management].”

Outside of this ongoing struggle, members of the Rhode Island environmental and conservation community are hopeful that existing programs and collaborations can be mobilized to identify where mature forests exist, and then to protect them. Through the Rhode Island Woodland Partnership and the state’s Forest Conservation Commission, stakeholders have developed working definitions of old growth; advocated for expanding state capacity to manage existing public lands; and advanced an understanding of how informed stewardship of Rhode Island’s core forests can contribute to the broader effort to preserve ecosystem integrity, serve the state’s climate and carbon goals, and build a better home for all.

Learn more about the status of Wildland conservation in Rhode Island in this State Summary from the Wildlands in New England report.

Massachusetts

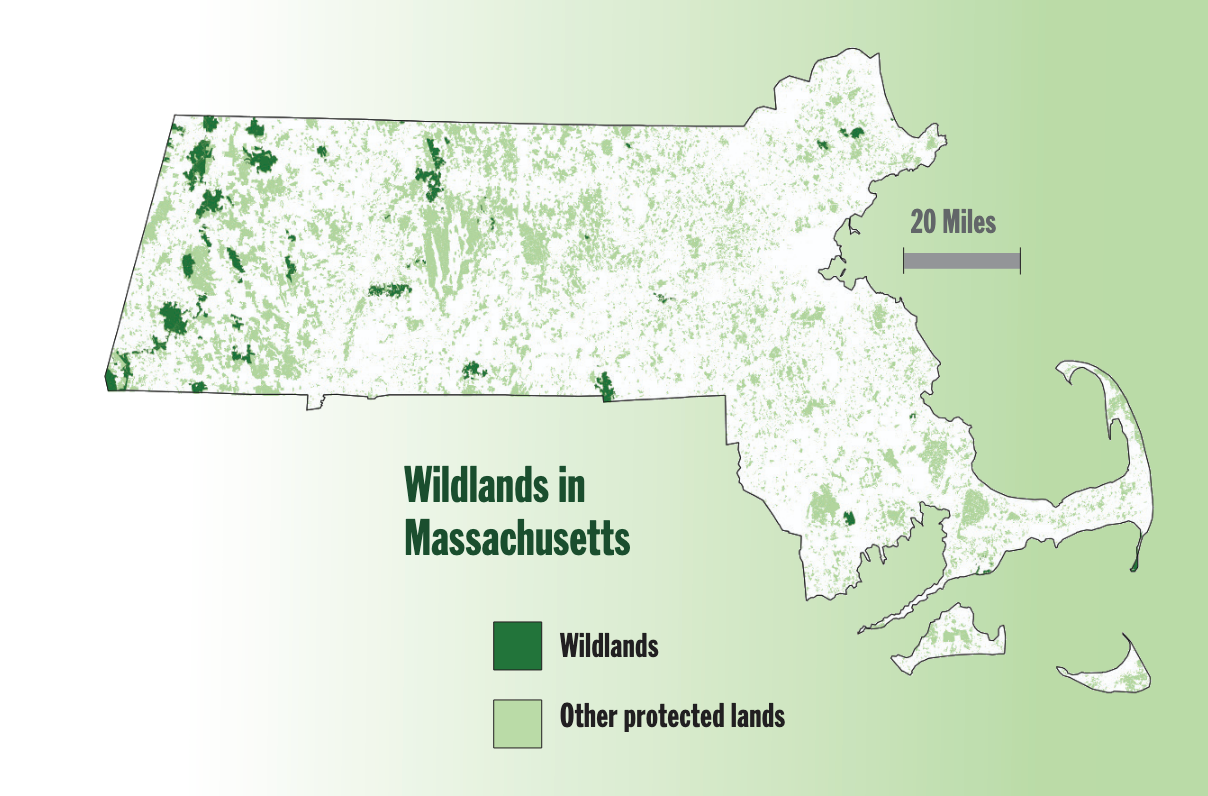

The Massachusetts Land Acquisition for Forest Reserves Grant Program seeks to advance the protection of Wildlands across the state. Currently, just over two percent of Massachusetts’ land is protected in a largely unmanaged or wild state. Figure from Wildlands in New England: Past, Present and Future

In the Spring 2025 issue of From the Ground Up, David Foster’s “The Massachusetts Commitment to Forest Reserves” outlined how Massachusetts’ Forests as Climate Solutions Initiative led to a new grant program to promote the expansion and protection of mature and passively managed forests across the state. Now open for its second round of applications, the Land Acquisition for Forest Reserves Grant Program remains unique in the region—no other state in New England makes public funding available specifically for projects that protect passively managed forests on private lands.

This grant program seeks to “protect resilient forests that will mature over time without active management or significant human intervention.” This complements the priorities laid out in Massachusetts’ three other primary sources of forest conservation funding. The first program, the Local Acquisitions for Natural Diversity (LAND) Grant Program, is state funded and prioritizes passive recreation opportunities and compatibility with existing open space plans without preference to management techniques. The second major source of forest conservation funding is the federally funded Forest Legacy Program, which supports projects that permanently protect forests for a variety of values including recreation, water quality, wildlife habitat, and forest products. The third major funding source is the federally funded Land and Water Conservation Fund, which funds projects that emphasize community access and the protection of working lands. These programs; the other existing public, private, and philanthropic sources of funding; and now the Land Acquisition for Forest Reserves Grant Program all contribute to a wide array of options to landowners and conservation partners seeking the “right fit” for any particular project.

In 2025, the Land Acquisitions for Forest Reserves Grant Program awarded nearly $5 million to protect over 1,400 acres of forests across the state. To put this in context, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation manages over 110,000 acres of forest reserves and is working to meet the Healey-Driscoll administration’s ambitious target of protecting 300,000 acres of forest reserves by 2030. Now, without federal funding available to flow through this program, Massachusetts is continuing to fund the work exclusively with state dollars, and at a smaller scale. Though this particular program is a welcome and important addition to the myriad sources of public funding for forest conservation, achieving the broader goals of expanding forest reserves to 10 percent of Massachusetts’ forests will need continued collaboration and investment from all corners in the years to come.

Learn more about the status of Wildland conservation in Massachusetts in this State Summary from the Wildlands in New England report.

Vermont

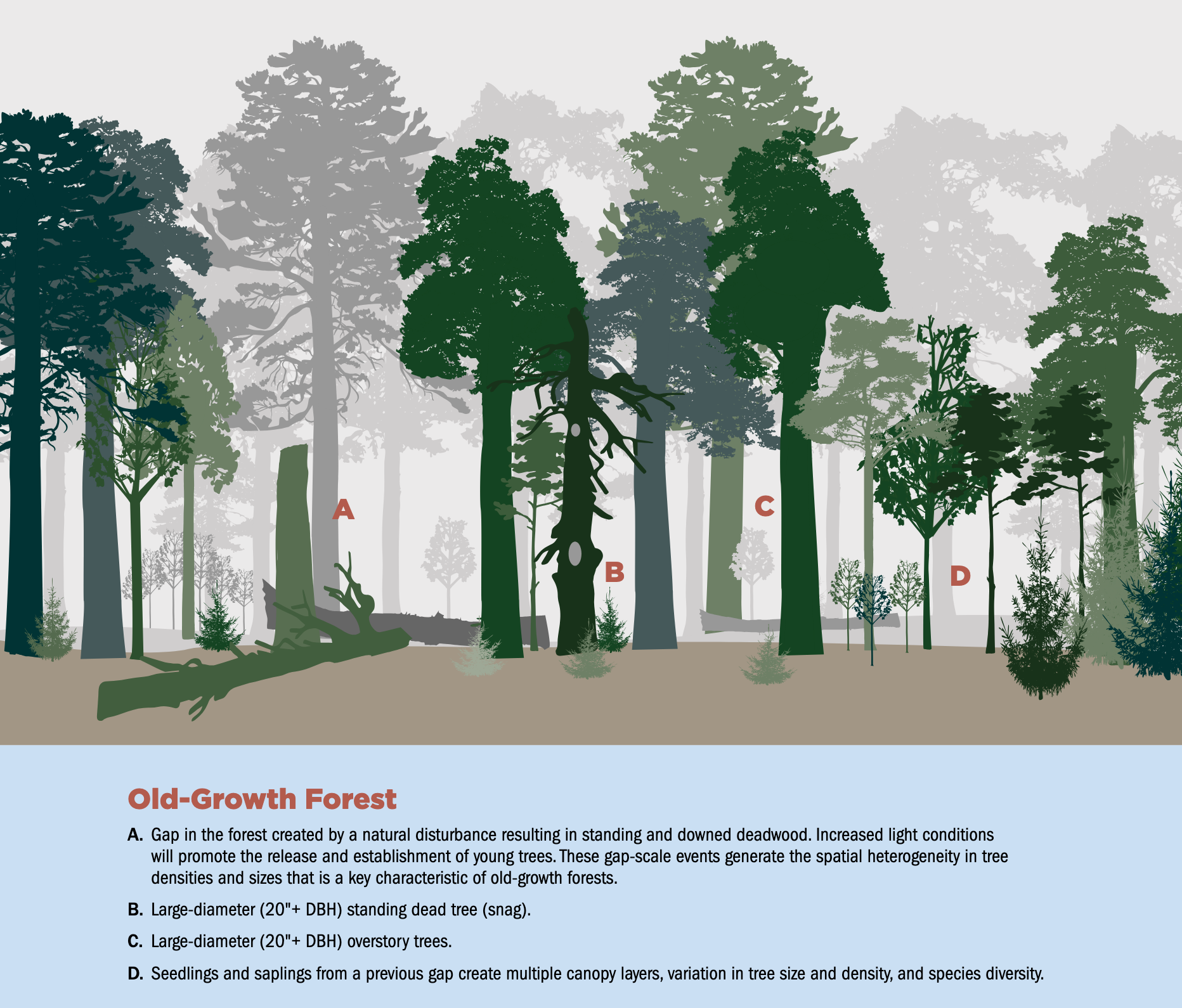

What are “old-growth characteristics?” This graphic provides a basic overview of the types of conditions that Vermont landowners might emulate by enrolling in the Reserve Forestland program, and managing their land either passively, or actively using ecological forestry principles. Image from Restoring Old-Growth Characteristics to New England’s and New York’s Forests by Anthony D’Amato and Paul Catanzaro. See more on this publication and how it informs Vermont landowners interested in managing woodlands to enhance old-growth characteristics in our Read/Watch/Listen section.

All six states in New England have their own Current Use programs designed to offer landowners property tax discounts if they keep their forests or farmlands in their current natural and working conditions—farms as farms or forests as forests. While most states in the region require landowners looking for the most favorable tax benefits to manage their forest lands for active harvest and timber production, in 2023, Vermont established the Reserve Forestland program within its Use Value Appraisal (UVA) Program to extend current use eligibility to landowners who are managing forests to support “old-growth characteristics” versus managing for commercial wood products.

Within a parcel eligible for the Reserve Forestland program, forest management can be active, with hands-on intervention to remove invasive species or to diversify species, for example, or passive, by letting a forest already “on the right track” grow older with minimal interference. The UVA program is popular in Vermont, with nearly 2 million acres of forests enrolled, representing over half of all privately owned forests in the state. Vermont officials estimate that nearly 15 percent of all wooded parcels eligible for enrollment would qualify as eligible under the new Reserve Forestland program. In early 2026, state officials should release the first analysis of enrollment levels and impacts, hopefully providing insight to other states interested in supporting alternative forest outcomes through their respective Current Use programs.

Other important conservation efforts in Vermont have been reported on in previous issues. Implementation of Act 59, Vermont’s Community Resilience and Biodiversity Act (see previous article on the origins of this law), is currently underway, with a draft plan available for review at the Vermont Conservation Plan Project.

Gus Seelig has written in these pages about the ongoing efforts to blend affordable housing and conservation, and he was one of several panelists on the topic at the recent Regional Conservation Partnership Network Gathering in November.

Important updates to Vermont’s Land Use Law, Act 250, were reported on previously, and implementation of these updates is underway at present, with stakeholder groups working to iron out the details. We will report more on this as progress unfolds.

Learn more about the status of Wildland conservation in Vermont in this State Summary from the Wildlands in New England report.

Connecticut

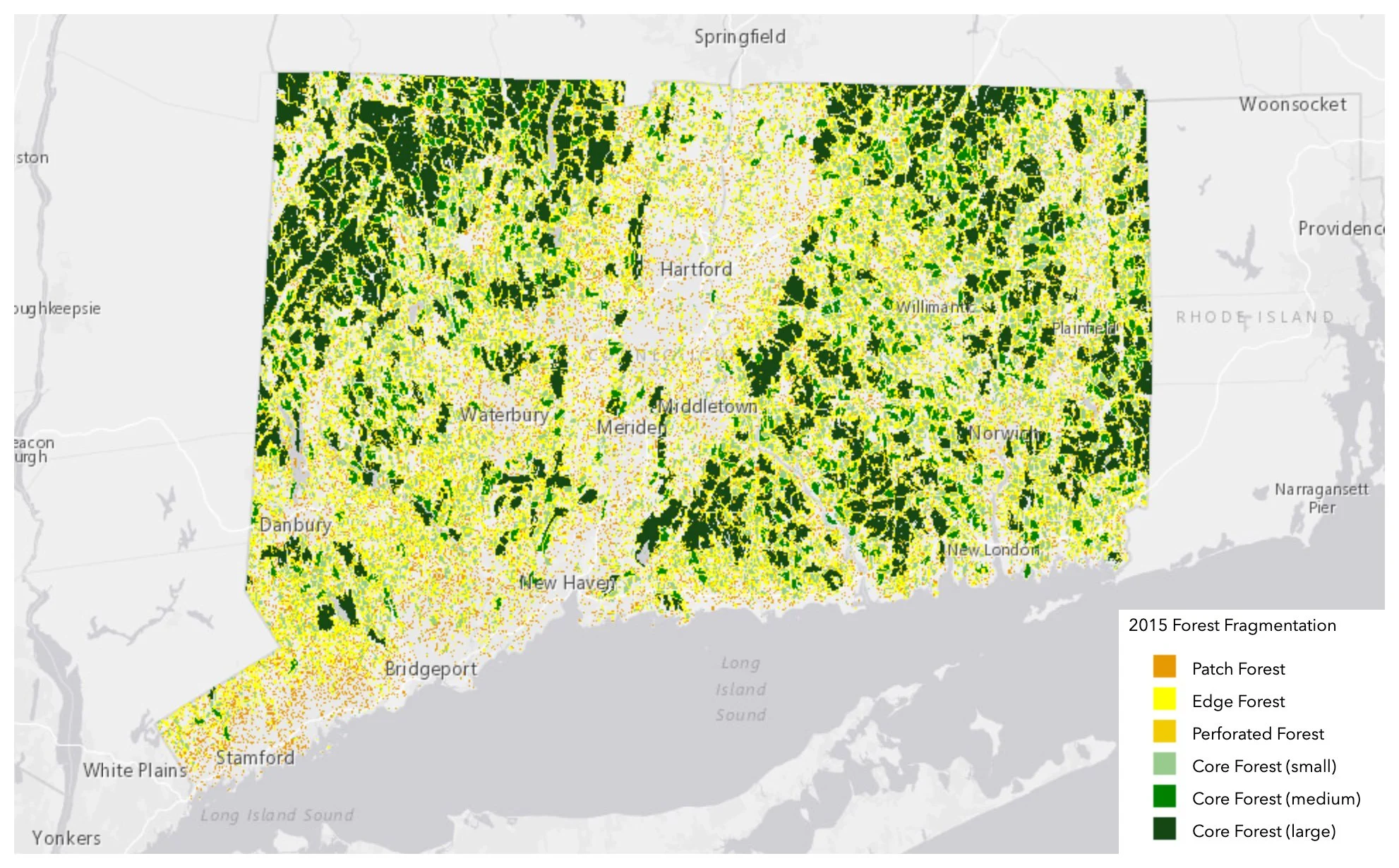

Forest policy in Connecticut has focused primarily on the preservation of and connectivity between “Core Forest” blocks. In the graphic above, darker green represents larger blocks of intact forest, with yellow and orange depicting forests that have been fragmented by roads, development, or agriculture. Figure retrieved from the UConn Center for Land Use Education & Research (CLEAR)’s Landscape Fragmentation tool

There has been relatively little attention paid to old-growth forests in the Connecticut legislature in recent years, but significant groundwork has been laid to support the identification and protection of mature forests in the near term. Two efforts from lawmakers and conservation advocates have led to substantive debate on if and how state law should govern how public and private lands are managed for forest resilience. In 2021, a working group of state agency leaders, conservation advocates, and environmental equity stakeholders was convened to develop “Policy on Resilient Forests for Connecticut’s Future” (impeccably shortened to “PRFCT Future”). The PRFCT Future report outlined a sweeping list of policy recommendations that would collectively improve the stewardship and protection of Connecticut’s woodlands, including ambitious new goals for expanding the canopy cover and incentivizing underground utility installations to avoid further fragmentation. The report’s only reference to mature or old-growth forests, however, refers to the aging forests of Connecticut as more of a liability than an asset: “Connecticut’s forests themselves are also aging—most trees forming the dominant canopy are old enough for deleterious effects of forest pests and storm damage to impact forest resources and uses, increasing the need for science-based stewardship.”

In 2023, HB 6610 or “An Act Concerning ‘No-Net-Loss’ of State Forestlands” was brought before the House Environmental Committee. This bill, modeled after similar legislation enacted in New Jersey, would have required state agencies to develop a compensatory reforestation program for any woodlands impacted on state property. No-net-loss programs are often seen as important policy mechanisms that, at best, prevent continued deforestation and fragmentation, and, at least, create some financial cost associated with the removal of standing trees. Supporters of HB 6610 explored a possible amendment to this ambitious bill specifically pertaining to old-growth forests to address the discrepancy in value and ecosystem services between removing an acre of diverse, mature forestland and replanting with an acre of new trees. That amendment was ultimately unsuccessful, and, with opposition from both the State Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the Department of Transportation, the No-Net-Loss legislation died in committee soon after.

In 2026, Connecticut officials and environmental leaders will update the state’s now-expired “Green Plan” to set conservation targets and management guidance for state agencies for the next five years. There is cautious optimism within the environmental community that redrafting this plan will provide an opportunity to introduce old-growth-specific considerations and protections to state policy without the need to return to the legislature moving forward.

Learn more about the status of Wildland conservation in Connecticut in this State Summary from the Wildlands in New England report.

New Hampshire

One of New Hampshire’s best examples of standing old-growth forests can be found in the Sheldrick Forest Preserve in Wilton. The black birch tree and iconic stone wall perfectly illustrate how some of the oldest trees and forests in the region are still very much tied to cultural and human management of the landscape. Image courtesy of Mike Gagnon, University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension

One unique feature of New Hampshire’s forests is the size and scope of federally owned and managed forestland. The White Mountain National Forest (WMNF), with over 800,000 acres of mountains, managed woodlands, and wilderness areas, represents nearly 20 percent of all the forested landscape in New Hampshire and 15 percent of the entire state’s land mass. Perhaps it is the size and visibility of the WMNF, with management decisions set by federal policy versus state law, that has led to a relatively quiet old-growth forest policy landscape in the New Hampshire legislature over time. Only a single, ill-fated bill related to old-growth forests has been introduced over the past 15 years.

With such significant federal holdings, the integrity of New Hampshire’s mature and Wildland forests (see this State Summary for an overview on Wildland conservation in the Granite State) relies disproportionately on federal policy. The Biden Administration’s Executive Order 14072 instructed relevant federal agencies to identify and steward mature forests to promote old-growth characteristics nationwide, prompting a comprehensive review and research process that wrapped up just in time for the Trump Administration to release its own executive order in January 2025 that revokes all such preference for old-growth forests in the name of Unleashing American Energy and natural resources.

Despite the general lack of state-level old-growth forest policy, there is an ongoing legal process that may eventually determine how forests protected with state-funded conservation easements may or may not enroll in carbon markets to generate financial returns while letting the forest grow. The ongoing challenges in both the legislature and New Hampshire courts, as well as sometimes heated public discourse, have the potential to directly influence if and how public lands are managed for carbon or old-growth characteristics.

Learn more about the status of Wildland conservation in New Hampshire in this State Summary from the Wildlands in New England report.

Alex Redfield is the Policy Director for Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities. On the farm, in state government, and in conservation policy circles, his work for the past 20 years has centered on supporting a just transition of New England’s landscape toward an equitable future. He lives in South Portland, Maine.