Old-Growth Forest Network

Twelve Years of Creating Access to the Ancients

Editor’s Note: The Old-Growth Forest Network (OGFN) has done perhaps as much as any organization in raising awareness of the importance of old-growth forests in the United States. Started by Joan Maloof and now ably directed by Sarah Adloo, the organization played a pivotal role in organizing the recent Northeastern Old Growth Conference. I had the pleasure of walking in the forest with Joan before the 2023 conference, and what struck me in that walk was her fascination with the smallest things—fungi, slime molds, and mosses—along with the majestic white pines among which we walked. It is this fullness of perspective that makes Joan a perfect advocate for the protection of old-growth forests. – Liz Thompson

“What is an old-growth forest?” That is the most common question I get, and, unfortunately, it is also my least favorite. At every old-growth forest conference, including the recent one held in Ripton, Vermont, there is a whole session dedicated to this very question, and many of us walk away disappointed—in part because there is no black-and-white answer. It is more shades of gray…or should I say green? As a result, some people have started using creative terms like “old growthy” or “old growthiness” to avoid any line dividing is from isn’t.

Old-Growth Forest Network County Coordinators hiking at Sunapee State Park in September 2021. Left to right: Chris Kane, Sarah RobbGrieco, David Govatski, Christine Tappan, Leslie Randlett, and Vicki Brown. Photo © John Pastore, Courtesy of Old-Growth Forest Network

After the discussion of definitions usually comes the question of “how much?” As in “how much is left?” It’s tricky to answer if you haven’t drawn definitive lines, and in many places the groundwork to age forests hasn’t been done. Only in the past few years have we seriously tackled the remotely sensed signature of these older forests—to answer both “how much” and “where.” For a long time we have known more about the craters of the moon than we have about the Earth’s forests; as a result, we still only have rough estimates regarding “how much.”

In the 1980s, Dave Foreman (founder of Earth First!) and his comrade John Davis were discussing these very questions of “how much” and “where” regarding the old growth in the eastern United States. In those days we didn’t even have a rough guess. In response to the questions from Foreman and Davis, Mary Byrd Davis, mother of John Davis, put her research skills to work. In 1993, she published the first edition of Old Growth in the East: A Survey, a first attempt to summarize where remnants of old growth were in the east. A few years later she edited the 1996 book Eastern Old-Growth Forests: Prospects for Rediscovery and Recovery. Together with her co-authors they estimated that less than one percent of the eastern forests remained uncut. The estimates for old growth left in New England was less than half of one percent. In 2003 she revised and updated the Survey, and to this day it is the most complete inventory available of old growth in the east.

In the preface to her edited volume, Mary Byrd Davis wrote: “We are between two forested worlds—the natural forest of presettlement North America and the recovered forest of the future… The earlier forested world is not dead. We are studying and struggling to preserve its living remnants. And we do not believe the future forest is powerless to be born.”

I used Davis’ Survey as a source for finding eastern old-growth forests for my own book project: Among the Ancients: Adventures in the Eastern Old-Growth Forests. During my visits to ancient forests in the 26 states east of the Mississippi River, I thought often of Davis’ statement about the two forested worlds—the remnants and the future forest. I wondered who was doing the work to preserve the rare old growth that was left. My inquiries turned up nothing substantial. There were the large national groups, like the Sierra Club and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), that cared about old growth—but it wasn’t central to their mission. Then there were the smaller groups working hard to protect the old growth in their regional forests, but it seemed that no group was focused solely on preserving old-growth forests across the nation, regardless of ownership.

That became the focus of the organization I started in 2012—the Old-Growth Forest Network (OGFN).

In addition to preserving the scant one percent of old growth left in the east and the slightly larger percentage in the west, our mission is to also help create future old-growth forests by preserving some of today’s once-cut but long-in-recovery forests. This is a huge mission, made slightly more manageable and measurable by aiming for at least one forest in each county that can support forest growth, approximately 2,370 counties in the United States.

We look for forests that are:

as old as possible;

relatively accessible;

open to the public; and

protected from commercial harvest. (The most challenging of all the criteria, our most important task has become working with landowners to get their forests strongly protected.)

Once all of these criteria are met, a forest can be inducted into the Old-Growth Forest Network and listed on our website (www.oldgrowthforest.net), and anyone can find it and visit.

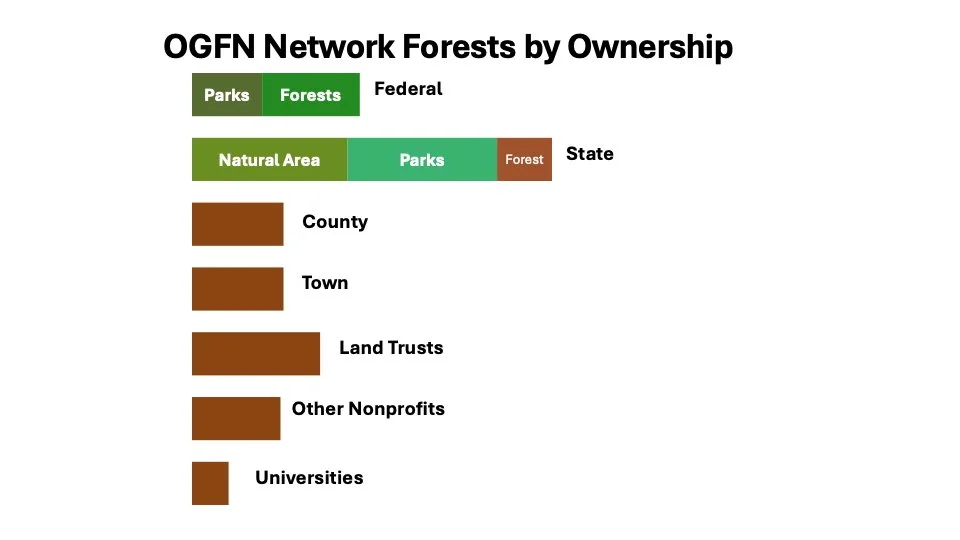

Any entity can own the forest as long as it meets the four criteria. Now that we have over 300 forests in 40 states, we have a good sense of our ownership categories and the obstacles in each.

Image courtesy of Old-Growth Forest Network

State-owned land has turned out to be our largest ownership category. Within that category, state natural areas are very important because in many cases they are the only state land use that doesn’t allow commercial harvesting. State parks are another large category in the Old-Growth Forest Network. Most people assume that state parks are protected from commercial timber harvesting, when usually they are not. Only eight out of the 50 states have protected their parks from commercial logging. In those eight states, which include California and New York, we have a number of State Park forests in the Network. When people see harvests in parks in states like Ohio, Florida, or Pennsylvania, they may be angry and confused. Even old-growth forests in parks are not protected from harvest unless they are in a natural area. We believe natural forests in all state parks should be protected from harvest.

Federal land is the second largest category that our forests fall into. Many national parks contain old-growth forests, and these forests are strongly protected. As a result, some of the most iconic forests in the nation are included in the Old-Growth Forest Network, including parts of Sequoia National Park, Olympic National Park, and Yosemite National Park.

National forests comprise another of the large categories for forests in the Old-Growth Forest Network. As we look at this category, we need to keep in mind that not all states have national forests. National forests, in general, are not strongly protected, and often they are actively managed, but there are land management categories in the national forests that do have strong protection, such as wilderness areas and research natural areas. Our network forests are mainly in these special management zones.

The federal wilderness areas, in particular, are our nation’s most strongly protected lands. Most wilderness areas in national forests were created as part of the Wilderness Act of 1964, the result of a decades-long effort beginning with Aldo Leopold’s effort to establish the first federal wilderness area in the Gila National forest in 1924. It takes an act of Congress to create federal wilderness areas, and that cannot be undone administratively through the executive branch.

“For a long time we have known more about the craters of the moon than we have about the Earth’s forests”

Other public lands that are represented in the Network are those belonging to counties and towns. County- and town-owned forests can be especially vulnerable because they often don’t have strong legal protections in place, and the commissioners or council members or selectmen who are responsible for them can easily be swayed to manage them for profit. Even after many decades of protection, vociferous new council members, backed by a local forester, can get the majority votes they need to cut the forest—with “balancing the town’s budget” being the primary driving goal. But on the flip side, just as these county and municipal forests can be easily destroyed, they are often easier to preserve than federal or state-owned land. A vote by a sympathetic council can turn a county park into a county wilderness park, or can put a permanent “no-log” easement on a town park. OGFN has been involved in many of these efforts to successfully educate council members and selectboards about the importance of preserving their forests for the future.

A significant portion of OGFN forests are owned by nonprofits including land trusts like TNC. But just because an older forest is owned by TNC or another land trust does not mean that it is protected from cutting. Donors to TNC are often surprised and disappointed to learn that commercial timber harvesting sometimes takes place on TNC-owned lands—even if it is in the name of “restoration.” The Old-Growth Forest Network includes a number of properties owned by TNC, but sometimes these properties were donated with strong protections. At a minimum we require an extra layer of protection, such as a signed Memorandum of Agreement stating that the forest will not be cut.

Property owned by a land trust is often protected only by the commitment of its board of directors, and boards change. We encourage all land trusts to institute another layer of protection, such as a no-log conservation easement or deed restriction recorded with the land records. This gives the property legal protection regardless of who the board members are. Northeast Wilderness Trust has been one of the most exemplary land trusts in regard to truly protecting land as forever wild. The OGFN includes some forests owned by Northeast Wilderness Trust.

Our project has made great strides in the past dozen years, but it is just ten percent of the way to completion. Because not every county contains even a remnant of old growth, many of the forests in the Network are second growth on their way to becoming old growth again. In conclusion I will quote Mary Byrd Davis again: “The earlier forested world is not dead. We are studying and struggling to preserve its living remnants. And we do not believe the future forest is powerless to be born.” She couldn’t have foreseen the creation of the Old-Growth Forest Network, but if she could have, I think she’d agree that it is a project with a unifying mission and a strong future.

To learn more about the Old-Growth Forest Network, visit www.OldGrowthForest.net.

Joan Maloof with a red oak in Schoolhouse Woods, Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. This forest was recognized as “old growth” and was managed as a state park, but it was not protected from harvest. It took the creation of a new state bill to protect it, and it is now in the Old-Growth Forest Network. Photo courtesy of Baltimore Sun

Presentation from the Northeastern Old Growth Conference 2025

September 17-21, 2025 | Middlebury College - Bread Loaf campus | Ripton, Vermont

View all recorded presentations from the conference.

Dr. Joan Maloof is founder of the Old-Growth Forest Network; Professor Emeritus in Biology at Salisbury University; and author of numerous articles and books, including Nature’s Temples: A Natural History of Old-Growth Forests, Among the Ancients: Adventures in the Eastern Old-Growth Forests, and Treepedia. Her newest book, Forty Ways to Know a Tree, will be released in April 2026.