ISSUE #7 • SUMMER 2025

From the

Ground Up

Conversations about conservation, climate, and communities in New England.

ARTWORK BY JANINE WEISS - WATERCOLOR WITH PEN AND INK - VIEW THE FULL IMAGEWelcome to the Summer 2025 Issue

Summer is a time of hope. A time of plenty. A time of sun, of rain, of growth.

This summer, filled with all of these things, is also filled with a sense of loss and despair. We are in a time of immense political and economic turmoil, and it may take decades to recover.

Feeding ourselves is central to survival. That’s why farmland and food take center stage in this issue.

Access to farmland is at the heart of an integrated vision of conservation for New England.

This might not seem obvious at first glance. Little more than five percent of New England is cropland and pasture; some 80 percent is wooded. The pre-European landscape was even more heavily forested. One could make the case that conserving forest is what really matters, and that conserving New England farmland is a sentimental sideshow or a distraction.

But a growing number of conservationists are seeing the importance of farmland in the regional conservation picture. How we grow food is a fundamental part of our relationship with Nature: It is where industrial-scale production does profound environmental and cultural damage. It is also where we can build community strength and ecological resilience. How we grow food has a far larger impact, for good or ill, than the small percentage of the landscape it occupies.

In 27 years of New Entry Sustainable Farming Project’s work to support beginning farmers, we have often heard some version of the “advice” that, if someone really wants to be a farmer, “tell them to go back in time and get born into a different family.” The truth in this dark humor hints at the many systemic barriers that make entry into agricultural livelihoods feel near impossible in the United States. Farming is a daunting, capital-intensive endeavor that requires access to land, infrastructure, tools, and markets. The commodification of land and foodways has a long and complicated history with white supremacy in the United States that still impacts farmers of color and their ability to access land and farm operating capital. It is rooted in settler-colonial power structures with Indigenous land loss, Japanese-American land loss to internment camps, discriminatory lending practices against farmers of color, land theft from Mexican farmers of the Southwest, and the prevention of equity building for African Americans post enslavement via share cropping practices, acts of race-based violence, and other nuanced policies such as heirs’ property.

The history of the last five centuries of Swanville, Maine, is not unusual. The small town, a few miles from where the Penobscot River meets the North Atlantic, sits squarely in the territory of the Penobscot people. In 1630, the English crown granted two Massachusetts colonists the authority to settle and conduct trade within a 36-mile region of coastal Maine via the “Muscongus Patent,” beginning a period of land claims, title disputes, settlement expansions, and other colonial machinations that lasted nearly 150 years and contributed to the expulsion of Native people and subsequent incorporation, by white settlers, of Swanville and 30 other nearby towns. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Swanville and neighboring communities flourished on the bounty of the sea, their advantageous location near the logging runs of the Penobscot River, and the various natural resource-based enterprises powered by, at a peak of industrial development, 33 different dams built to harvest energy along the 10-mile run of the Goose River that flows from Swan Lake to Belfast Bay.

Conversations

Seeds and Sovereignty

An Interview with Leah Penniman

by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson (AEJ): Overall, how does our food system work now, and how would it be different if we got it right for people and justice and the climate, from seed to table?

Leah Penniman (LP): Today the food system is fundamentally based on stolen land, exploited labor, and a profit motive. Farmworkers, arguably one of the most important professions in the world, are not protected under the Fair Labor Standards Act or the National Labor Relations Act. They don’t have a right to overtime pay, to a day off in seven, to collective bargaining, to protections against wage theft or child labor.

Since the beginning of the agricultural system in the U.S., which was based on chattel slavery, workers have always been exploited. There are the huge disparities in terms of land ownership and access, and ownership is rooted in a legacy of attempted genocide and land theft from Native people and expulsion of Black people from their land holdings starting in the early 1900s.

Reflections

Wolves in the West, Wolves in the East

Views from Wyoming

by Liz Thompson

It was March, 1995—deep winter in Yellowstone National Park. Fourteen Canadian wolves had arrived in January and had been caged for two months to allow them to acclimate to their new environment. It was time to open the gates and set them free. By March 31, all 14 wolves had made their way into Yellowstone.

Mollie Beattie, pictured here with Bruce Babbitt and Mike Finley, was Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) from 1993 until her death in 1996. In that role, she helped to carry the caged wolves to their new home, and she oversaw their release and subsequent protection. She was a fierce defender of the Endangered Species Act, particularly its emphasis on the protection of habitat for endangered species. She knew that wolves needed to be protected, but more importantly, that they needed suitable and viable habitat.

Regional Perspectives

Six Pathways to Farmland Access

Models from around New England

by Alex Redfield and Marissa Latshaw

If we are to build a food system that thrives in our region, we must forge alternative pathways to support new farmers in accessing land and markets. The economics of small-scale, locally oriented, and ecologically responsible agricultural operations are incompatible with a marketplace defined by extractive production and global supply chains. Identifying and implementing strategies to facilitate this transition, despite the political and economic barriers to success, will require a combination of public policy tools, community support, and sufficient financing to make progress in the face of broader trends of farmland consolidation and conversion.

Here we highlight six unique approaches to land access from each of the six New England states. Innovative work is happening all around us—some thanks to generous donors and insightful policymakers, some resulting solely from good relationships with neighbors. These six profiles are offered to amplify just a few unique approaches that might resonate with you and your community.

Conservation in Action

Magalloway Conservation Initiative Aims to Protect 78,000 Acres in Western Maine

by Marissa Latshaw

In a landmark effort to preserve the natural heritage of western Maine, four prominent conservation organizations have joined forces to launch the Magalloway Project—a comprehensive, integrative initiative to permanently protect 78,000 acres of forests, rivers, and wildlife habitats in the Magalloway region. This ambitious endeavor not only seeks to safeguard critical ecosystems but also aims to bolster the regional economy through sustainable forestry and recreation.

Want to join the conversation?

We invite your questions, reactions, debates, suggestions, and contributions. Our editorial team is committed to expanding the chorus of voices needed to safeguard the health, resiliency, and vibrancy of New England’s communities—both human and wild.

Read, Watch, Listen

The Bookshelf

Essential reading from our editors and contributors.

ARTWORK BY JACO TAYLORBulletin Board

Events, updates, and announcements from our partners and friends from around the region.

NOTE FROM OUR EDITORS

Climate change, environmental degradation, and the global loss of biodiversity aren’t just one-time crises—they’re daily threats to human well-being and to all life on Earth. Tackling them demands a bold, integrated approach to conservation, bridging forests, farms, fisheries, freshwater and marine systems, communities, and industries across New England.

Each season, we share stories, essays, in-depth reporting, interviews, art, photography, and poetry that showcase the diverse voices of individuals who exemplify the promise of the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities vision—offering hope and momentum for positive change.

Our goal is to inspire action for policies and practices that safeguard New England’s land and water for all who make their home here.

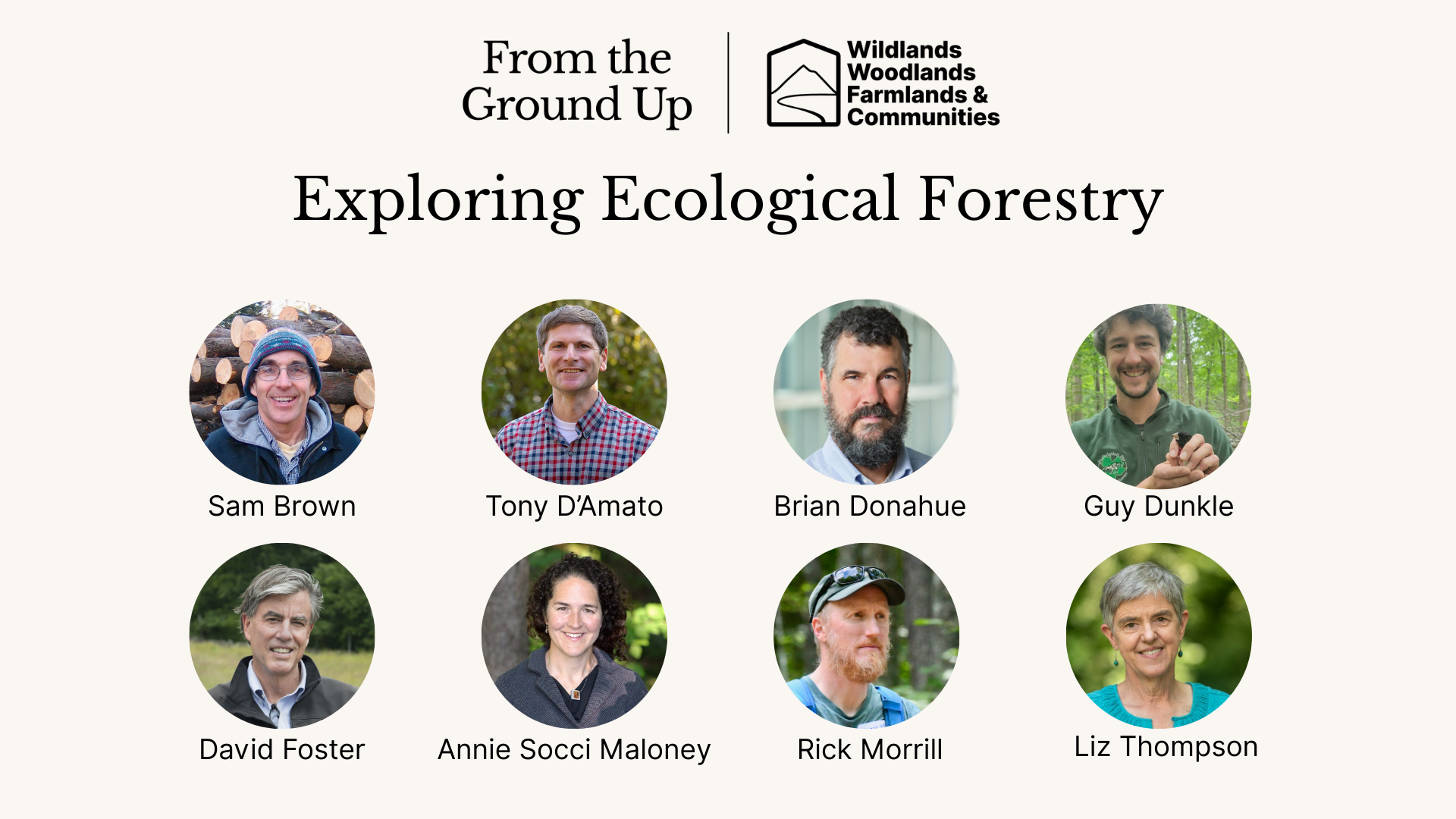

If you’re new to From the Ground Up, we encourage you to read “An Integrated Approach to New England Conservation and Community” by Brian Donahue.