ISSUE #9 • WINTER 2026

From the

Ground Up

Conversations about conservation,

climate, and communities in New England.

Artwork BY Gretchen Alexander - "Winter Beech" - VIEW THE FULL IMAGEWelcome to the Winter 2026 Issue

Old-Growth Forests: Past, Present, & Future

Each issue of From the Ground Up is an opportunity to look at different facets of an integrated conservation vision that includes natural Wildlands, carefully managed Woodlands, productive farmlands, and the communities of people and other organisms that depend on Nature.

Old-growth forests take center stage in this issue because they are a vital part of this vision. Inspired by the recent Northeastern Old Growth Conference, we bring together many voices to explore old-growth forests: what and where they are, why they matter, and how we can take action today to support the old-growth forests of tomorrow. Enjoy!

Bending low over the rotted log, a wonder of this forest was revealed. Slime molds.

“We think of things that are large and charismatic,” said Shelby Perry, Wildlands Ecology Director for Northeast Wilderness Trust (NEWT), who with wildlands ecologist Jason Mazurowski started off the 2025 Northeastern Old Growth Conference with a walk, archly entitled Small Wonders.

Sure, this wasn’t old growth. But look closer, she entreated: here was a salamander, peeping out at us with ancient amphibian calm from its hole in a downed log. We cradled a peeper in our palms, enjoying the delicate, cool touch of its toe pads before placing it ever so gently back in the forest duff. And then there was the miniature magnificence of the slime molds, the jewelry of the forest, vivid and finely wrought. And with such names! Chocolate tube slime, dog vomit, wolf’s milk—what was not to love?

The people who gathered recently for the 2025 Northeastern Old Growth Conference, surrounded by the glorious fall forest of the Green Mountains, had one shared goal: to learn more about Wildlands and old-growth forests.

Some came to learn how to measure trees. Some came to hear about new technologies for discovering old forests. Some came to hear how Indigenous people relate to the forested landscape. Some came to find out what they could do to protect Wildlands and old-growth forests in a time when public policies seem to be stripping protections away. Some came to hang out with like-minded people in a beautiful setting. Most came for all of these things.

Imagine for a moment that a cougar entering our region met kindness—not cars or guns or traps but people who welcome diversity and love the natural world. Consider, then, where Walker might have moved, after entering our region in 2011. Walker is the posthumously named young male cougar who wandered from South Dakota’s Black Hills to New York’s Adirondacks in 2010–2011, only to be killed by a car in Connecticut, while he was still looking for a mate. You can read his story in Will Stolzenberg’s powerful book Heart of a Lion. Had Walker not been killed by a speeding vehicle, where might he have most safely traveled through our region?

Conversations

From Loss to Hope

by John Elder

The mountain campus where we’ve gathered today has important things of its own to say about our topic of preserving and fostering old growth in the Northeast. In the decades following the Civil War, Joseph Battell purchased 30,000 acres surrounding what is now the Bread Loaf Inn. While growing up in the town of Middlebury he had been horrified by the heedless deforestation of his home landscape. His goal in adulthood thus became protecting these cut-over ridges from further depredation. The vast tracts of land he bought ultimately became the core of a new northern unit of the Green Mountain National Forest, while across Route 125 from where we are presently meeting stand the Bread Loaf Wilderness and the Joseph Battell Wilderness Areas, established in 1984 and 2006.

The deep forests of today’s Bread Loaf offer reminders that the conservation movement in America has often germinated in landscapes ravaged by deforestation.

Imagining Old Growth

Clues from the Past, Clues from the Present

by Charles V. Cogbill

In northeastern North America, most examples of “old-growth” forests are small remnants that are typically homogenous in composition, but not representative of the wider landscape. These stands are often well-documented, but are oddballs in location, environment, ownership, and history. Their restricted size also prevents them from fully exhibiting landscape-scale ecological processes, such as large natural disturbances.

The characterization of old growth based on these remaining small examples restricts the concept of “old-growth forest” in both space and time. The relevance of existing old growth to wildland designation, land conservation, restoration, climate change, or ecosystem services is therefore severely limited. A broader perspective on old growth is afforded by examining larger and more diverse areas and by examining historic conditions before widespread Euro-American influence.

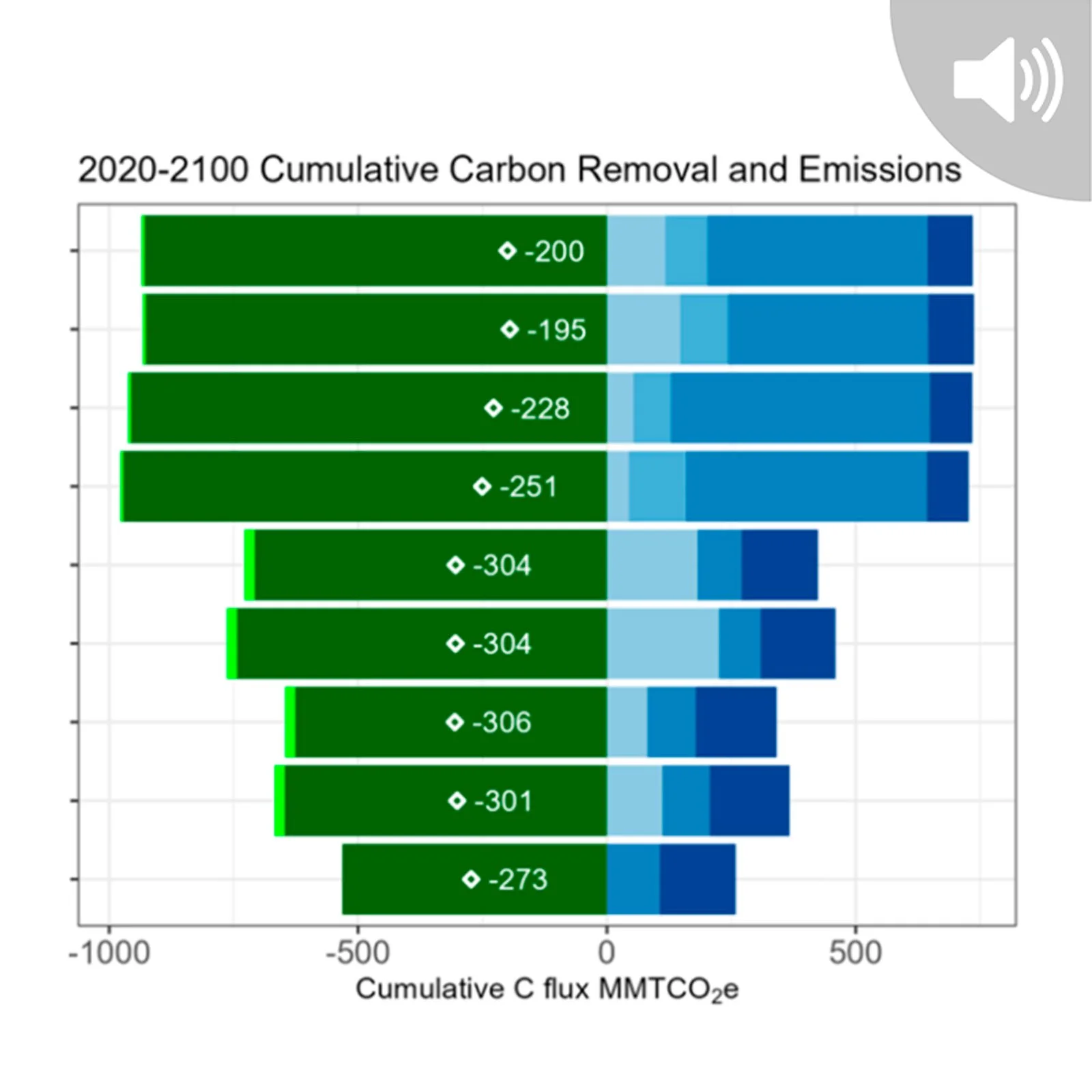

Managing for Biodiversity and Climate Mitigation

An Integrated Approach Guided by History

by David Foster

“Historically, the vast majority of Vermont’s landscape was old forest, and it is the original habitat condition for many species. The state’s native flora and fauna that have been here prior to European settlement are adapted to this landscape of old, structurally complex forest punctuated by natural disturbance gaps and occasional natural openings such as wetlands or rock outcrops… The closer the target is to the historic old forest condition, the greater the likelihood that the landscape will support all of Vermont’s native forest species and fully provide the forest’s ecological services.” - Vermont Conservation Design Part 2. Natural Communities and Habitats. Old Forests

Trees, Mothering, and Reciprocity

An Interview with Leslie Jonas, Indigenous Elder

by Liz Thompson

Liz Thompson: Thank you, Leslie, for taking the time to talk with us. I want to start with some terminology, some definitions. In your presentation at the conference, you talked about “intact forest landscapes” and the work that’s happening to inventory those lands. How do you distinguish between “old-growth forest” and “Intact Forest Landscapes” [IFLs]?

Leslie Jonas: Let’s talk about “Wildlands” too, as that’s a commonly used term in this discussion as well. All of these types of landscapes share important details, primarily that there has been little to no human disturbance. IFLs are vast, they are massive. Within IFLs, you can find old growth, you can find forests where there’s a lot of debris in the woods, lots of growth in multiple canopy layers, with a substantial amount of aboveground biomass, and with multigenerational stands of trees in the woods.

Reflections

At the Log Decomposition Site in the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, a Visitation

A poem by Derek Sheffield

Below thick moss and fungi and the green leaves

and white flowers of wood sorrel, where folds

of phloem hold termites and ants busily gnawing

through rings of ancient light and rain, this rot

is more alive, says the science, than the tree that

for four centuries it was. Beneath beetle galleries

vermiculately leading like lines on a map

to who knows where, all kinds of mites, bacteria,

Protozoa, and nematodes whip, wriggle, and crawl

even as my old pal’s bark of a laugh comes back:

Cat on the Mountain

A poem by Robert T. Perschel

Catamount, Mountain Lion

Cougar, Panther

Reality or myth?

Extinct?

Or living here, now?

Let the experts debate

I will call you what I will

“Ghost in the woods”

And have it all my way

You are the shadow by the brook

The voice in the thunder

Of a passing storm

My hair stands on end

And I grow wilder every day

Policy Desk

New England Policy Chronicle

Updates from Around the Region

by Alex Redfield

To support this issue’s focus on old-growth forests, this edition of the New England Policy Chronicle explores how state policy from around the region intersects with the protection and management of our oldest forests. Forest policy discourse in New England varies widely—from active attempts to legislate old growth identification and protection in Maine, to new programs to incentivize protection of maturing woodlands in Vermont and Massachusetts, to a fairly quiet policy landscape in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

Accelerating the rate of protection for Wildlands and passively managed forests in New England is a key goal of the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities (WWF&C) initiative. As part of that effort, WWF&C researchers and collaborators have created two valuable resources for allies around the region.

Conservation in Action

Old-Growth Forest Network

Twelve Years of Creating Access to the Ancients

by Joan Maloof

“What is an old-growth forest?” That is the most common question I get, and, unfortunately, it is also my least favorite. At every old-growth forest conference, including the recent one held in Ripton, Vermont, there is a whole session dedicated to this very question, and many of us walk away disappointed—in part because there is no black-and-white answer. It is more shades of gray…or should I say green? As a result, some people have started using creative terms like “old growthy” or “old growthiness” to avoid any line dividing is from isn’t.

After the discussion of definitions usually comes the question of “how much?” As in “how much is left?” It’s tricky to answer if you haven’t drawn definitive lines, and in many places the groundwork to age forests hasn’t been done.

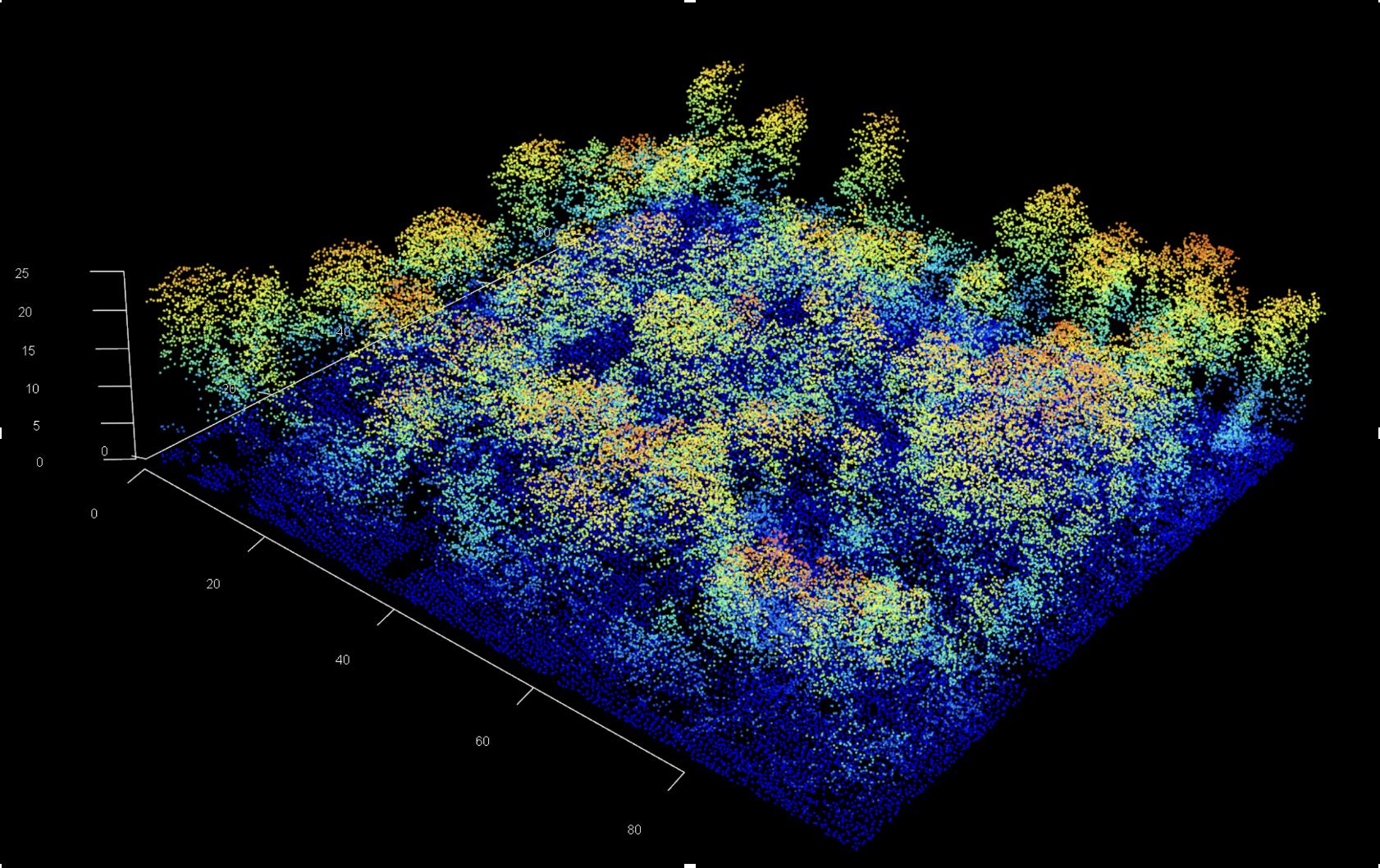

Seeing the Forest from Above

How a Good Map can be a Game-Changer for Old-Growth Forest Conservation

by John M. Hagan

In June 2022, we were replicating a birds-and-forestry study we originally conducted in the early 1990s in the unorganized territories of northern Maine. Much had changed about Maine’s commercial forest in the intervening decades. Clearcutting is much less common today, partly because of public outrage over clearcutting in the 1990s. The reduction of clearcutting, however, meant that more acres of forest were harvested with partial cutting each year, resulting in a vast forest landscape in a constant state of disturbance. Also, softwood (spruce and fir) were the desired species in the early 1990s for papermaking. Today, due to changes in technology, hardwood is preferred. With the backdrop of continued continental declines in bird populations, we wanted to know what these changes in Maine’s commercial forest might mean for regional and national bird conservation.

Finding Old-Growth Forests in Surprising Places

A Historic Perspective

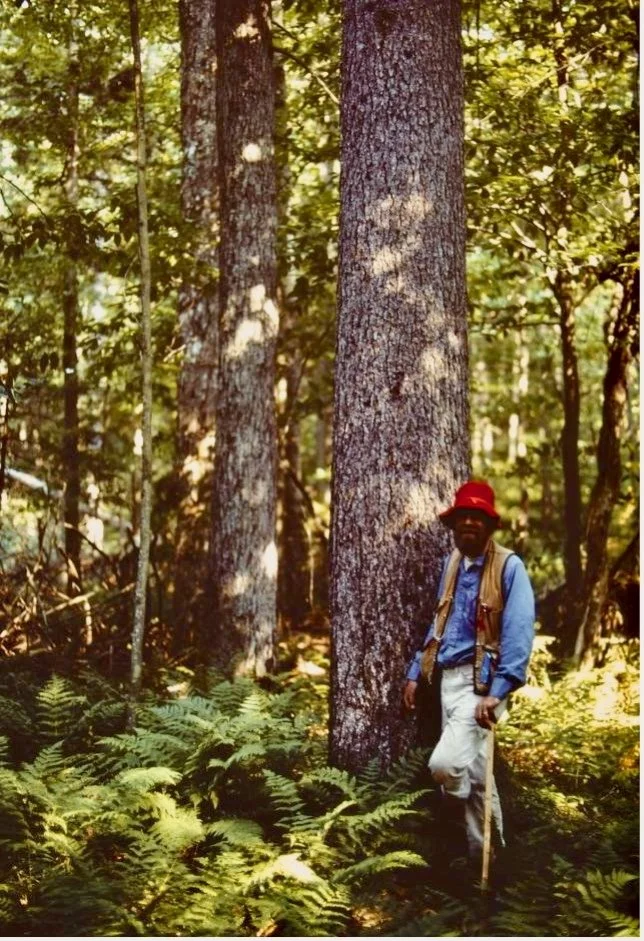

by David A. Orwig

Widespread clearing for agriculture and tree cutting for development, fuel, construction and other reasons throughout the nineteenth century removed most forests across the Northeastern landscape. So complete was this clearing that some estimates of remaining old-growth forests are less than 1% of the land. This leaves little old-growth forest to study, describe, and learn from. What is surprising is that there continue to be new “discoveries” of previously undescribed old-growth forests.

Yale ecologist Frank Egler and other early scientists proclaimed that there were no remaining old-growth (primeval) forests remaining across the entire Berkshire Plateau of Massachusetts, helping to perpetuate the myth that all had been removed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Want to join the conversation?

We invite your questions, reactions, debates, suggestions, and contributions. Our editorial team is committed to expanding the chorus of voices needed to safeguard the health, resiliency, and vibrancy of New England’s communities—both human and wild.

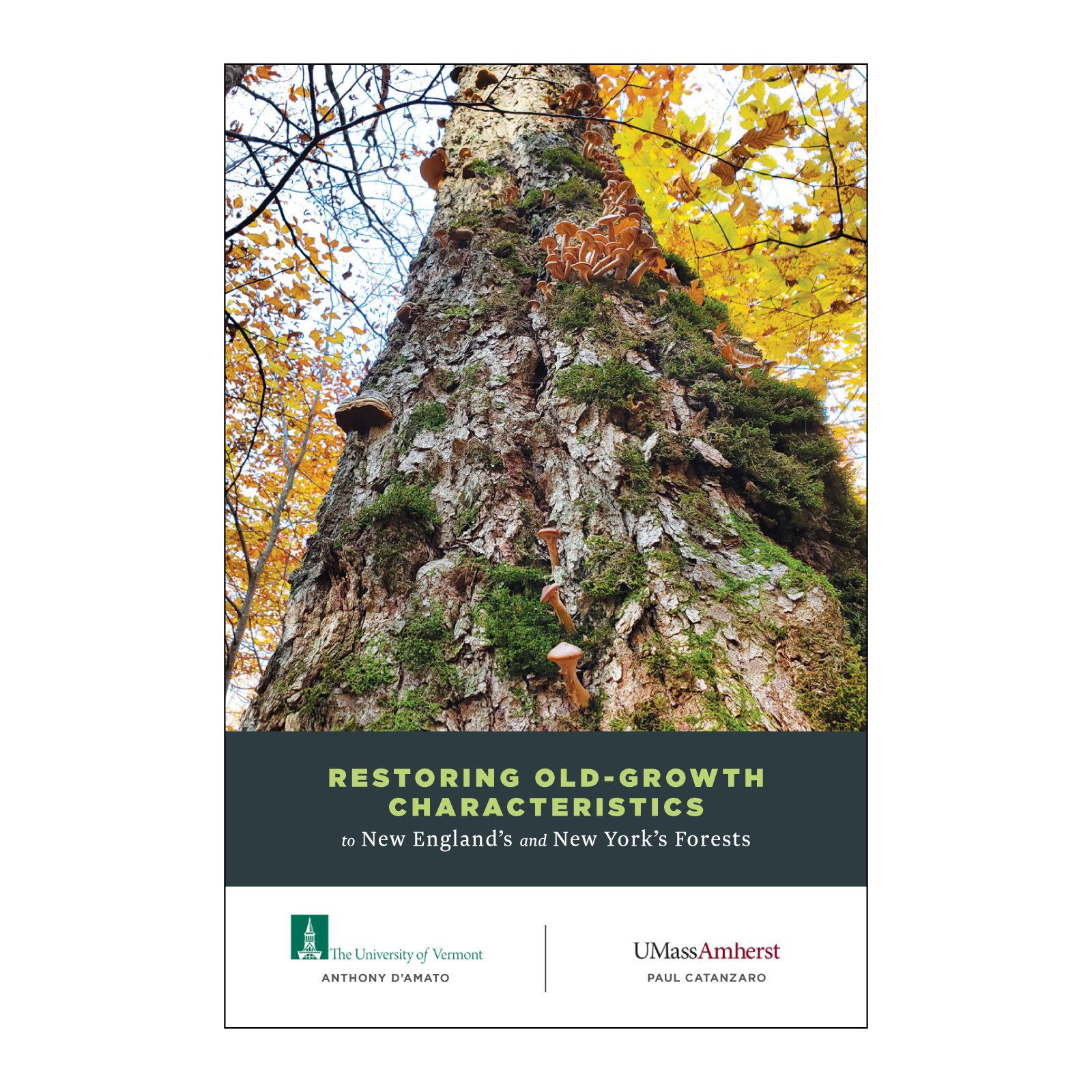

Read, Watch, Listen

The Bookshelf

Essential reading from our editors and contributors.

ARTWORK BY JACO TAYLORBulletin Board

Events, updates, and announcements from our partners and friends from around the region.

NOTE FROM OUR EDITORS

Climate change, environmental degradation, and the global loss of biodiversity aren’t just one-time crises—they’re daily threats to human well-being and to all life on Earth. Tackling them demands a bold, integrated approach to conservation, bridging forests, farms, fisheries, freshwater and marine systems, communities, and industries across New England.

Each season, we share stories, essays, in-depth reporting, interviews, art, photography, and poetry that showcase the diverse voices of individuals who exemplify the promise of the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities vision—offering hope and momentum for positive change.

Our goal is to inspire action for policies and practices that safeguard New England’s land and water for all who make their home here.

If you’re new to From the Ground Up, we encourage you to read “An Integrated Approach to New England Conservation and Community” by Brian Donahue.